It’s been remarkable to watch a sound from the streets of Lagos and Accra spread to the US Billboard charts and London clubs and festivals to become a cultural phenomenon around the world.

Too often when we discuss a pop-culture moment there’s a tendency to focus on what makes it cool, the eye-catching fashion, the new dance steps, the different sound, or the unusual visuals. But many times a moment can have a far more prosaic driver, aside from the usual requirements of great timing and exceptional talent.

The global reach of Afrobeats has had a lot to do with the power of social-media platforms like YouTube and Twitter and the innovative ways the small independent labels and artists in the early days of developing the sound jumped on these distribution platforms to share their music. This built an audience not just at home but with a growing diaspora market of first- and second-generation young Africans in the suburbs of cities like London and Atlanta earlier this decade.

🎧 For more intel on Africa’s music scene, listen to the Quartz Obsession podcast episode on Afrobeats. Or subscribe via: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher.

Early on, it meant Nigerian and Ghanaian artists, with next to no promotion or marketing, could build international audiences made up of those suburban diaspora kids who watched their music videos endlessly on Vevo.

Since then, digital music has rapidly monetized, especially over the last five years. Those once-small labels now benefit financially from Spotify’s rise and Apple Music—even if these services aren’t formally launched in the artists’ home markets yet.

Back at home, digital technology was just as important but in slightly different ways. The rise of the Afrobeats sound came alongside the growth of the major mobile operators like MTN and Glo, who competed for customers as they raced to build new markets. One way to do that way was to tap into the popularity of the artists and make them the faces of their brands.

Another was developing what became a lucrative market for ringback tones: there was a time you couldn’t call almost anyone in Nigeria without hearing a song playing in place of a traditional ringtone. Most of those songs were Afrobeats tunes, and were a key source of revenue for the artists and fledgling local music businesses in the early days. It wasn’t insignificant ancillary revenue for the telcos either; some industry estimates put the market sub-sector at $100 million a year.

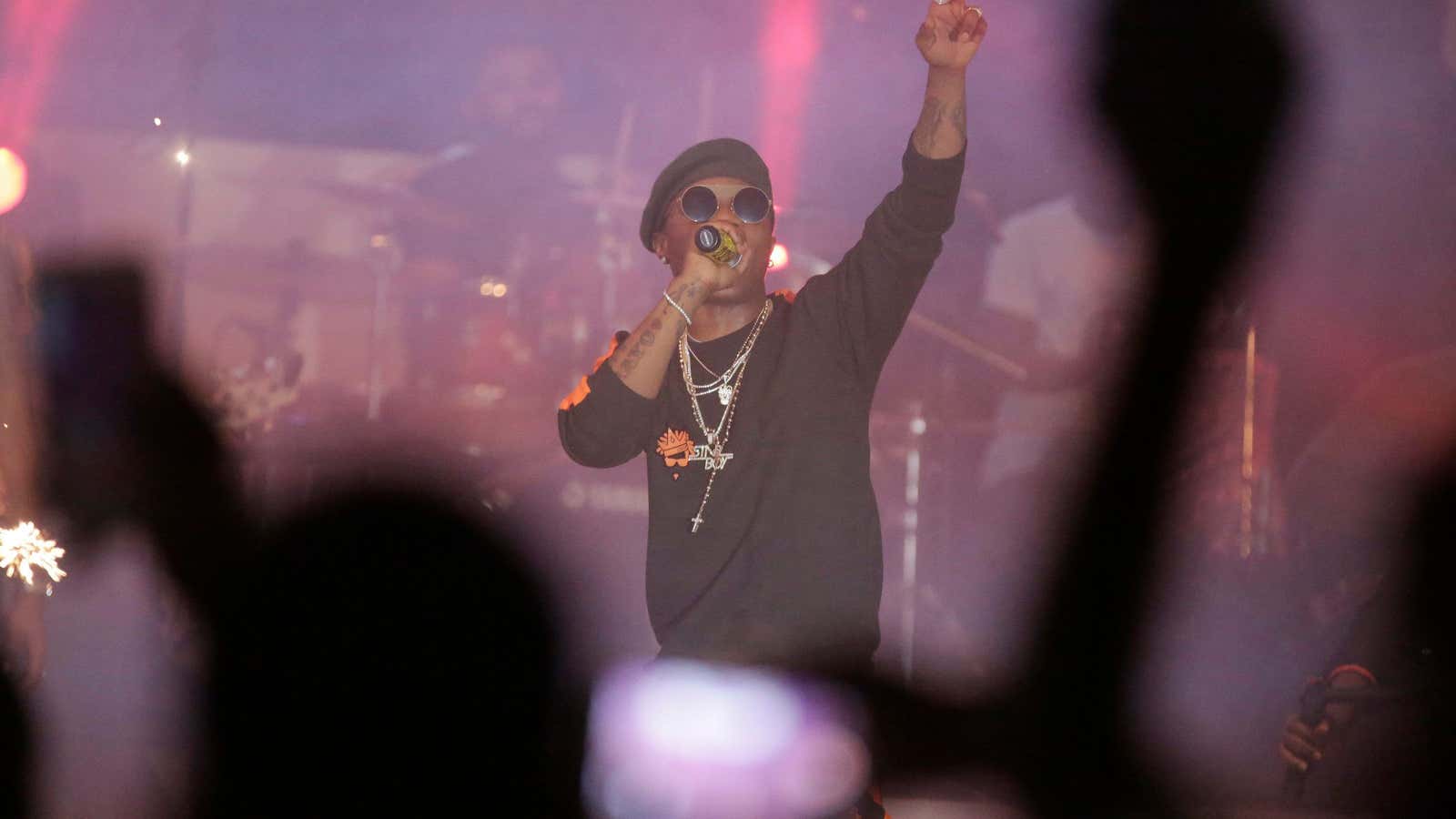

It’s been fascinating to see the arrival of the establishment global music business keen to tap into the energy of a fast-growing pop scene. Sony Music opened offices in 2016 and has the two biggest stars in Wizkid and Davido. Universal formally set up shop this year.

Major music companies might not be everyone’s favorites, and it’s true that they operate in a business that’s been turned on its head over the last two decades, but they still wield a huge amount of power and can help develop a formal industry. It would mean more local stakeholders from songwriters and promoters to managers and international-standard live venues all get fairly compensated. All that can help build a lasting ecosystem.

You could argue the global rise of Afrobeats backs up the thesis behind the quote: “Content is king, but distribution is queen and she wears the pants.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox