If you are part of the moneyed class in Africa, you are less likely to experience blackouts.

That’s the premise established in a paper published late last month in Cambridge University’s African Studies Review journal. The researchers say the continent’s rolling blackouts ”disproportionately” affect the poor and that a mix of political connections, socioeconomic factors, and skewed infrastructural development shelter the wealthy from experiencing electricity outages. As such, the richest neighborhoods receive about ten hours more electricity per day than the poorest areas.

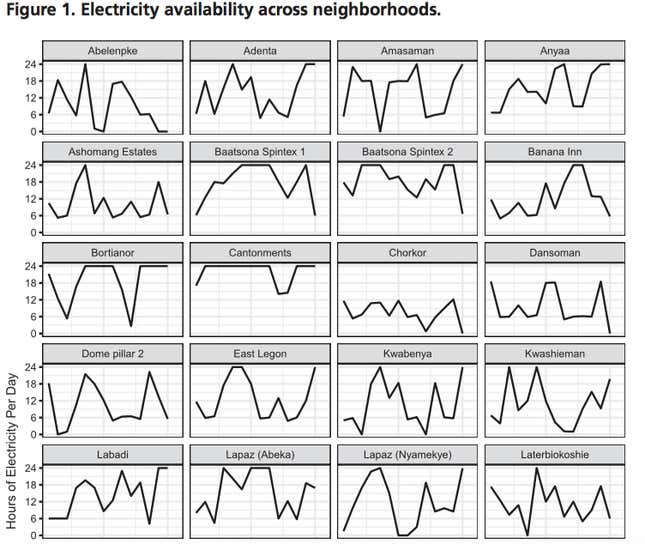

To understand the distributive politics of power cuts, the paper analyzed data on electricity availability across 32 neighborhoods in Ghana’s capital Accra. A stable democracy, with a rising economy and a high access to the power grid, the West African nation has in the recent past been bedeviled by persistent blackouts locally known as dumsor. The quality of housing and the tax brackets used by the city council to assess property levies were also factored into the methodology. The authors then corroborated that with a dataset from the Pan-African research network Afrobarometer which surveyed electricity supply in 36 African states.

The results show that the lowest housing quality quintile receives an average of about 7.5 hours of electricity per day, while the highest receives about 17.5 hours. Areas with higher tax rates also received power for almost 24 hours every day. The researchers argue that suppliers wouldn’t marginalize these areas in a blackout because “there is higher demand, higher marginal tariff rates, as well as higher and faster potential rates of payment.” Money also equals influence, and rich people, sometimes including the political elite, are able to petition and ensure they have better access. Electricity supply is also centralized in rich people areas because governments commit infrastructure development to well-off areas instead of poorer neighborhoods and slums.

This relationship between income and electricity availability showcases that being connected to the grid doesn’t mean access to electricity. Even as millions of more Africans get connected, some 600 million other still lack access to electricity—an issue that raises economic, social, and health concerns. Part of the problem is about supply being unable to meet demand—hence blackouts—even in the face of high-profile initiatives like the US-led Power Africa or the African Development Bank’s New Deal for Energy in Africa.

The marginalization of electric power also speaks to the fragmented nature of African cities, and the increasing urban problems they face. And even though research notes that democracies provide more electricity than autocracies, the example of Ghana shows that problems still do exist on specific country levels.

One reason why we don’t understand the problem of inadequate electricity supply, the authors said, was the lack of data or because its collection is difficult. To understand and address these glaring inequities once and for all, African governments could start by filling that information gap.