Nigeria is on edge with multiple internal security conflicts as it prepares for tense elections

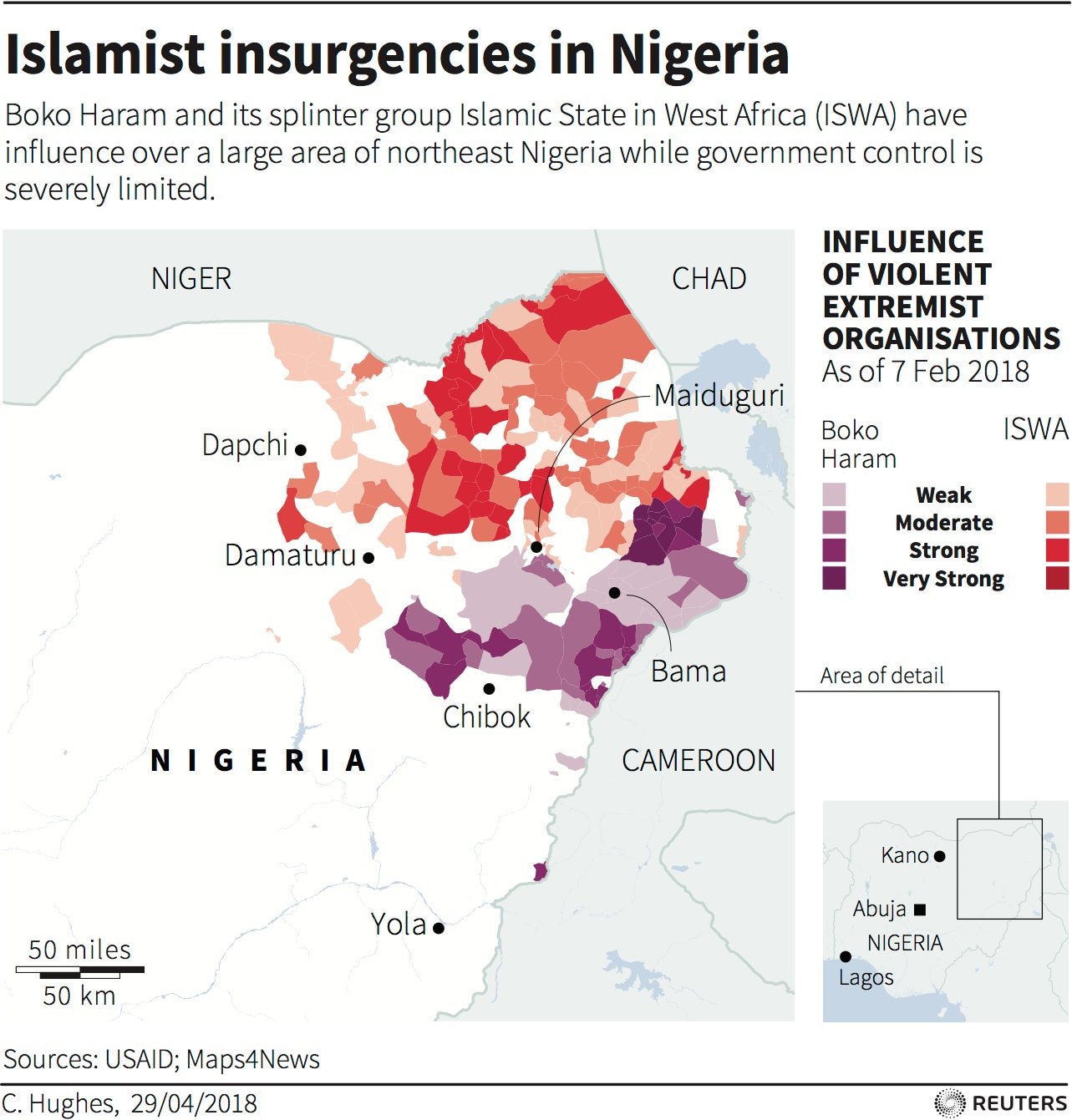

On Nov. 18, news broke about an attack on an army base in the village of Metele in northeastern Nigeria by suspected members of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), a splinter group of Boko Haram, the terrorist organization.

On Nov. 18, news broke about an attack on an army base in the village of Metele in northeastern Nigeria by suspected members of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), a splinter group of Boko Haram, the terrorist organization.

The ambush, which left 114 soldiers dead, is one of the most recent in a series of attacks by the terrorists on the Nigerian military which have been occurring with increasing frequency since mid-2018.

The terrorist group is notorious for suicide bombings of crowded market places and places of worship as well as the abduction and killing of civilians in Nigeria’s northeast. In the run-up to the 2015 polls, the group managed to force the elections to be postponed by six weeks while government forces successfully fought to reclaim territory.

However, the organization has recovered from those losses and despite its split into two groups: main Boko Haram and ISWAP, it has inflicted damaging hits on the military. The recent attack in Metele has made the war against Boko Haram, which the government claimed has been “technically defeated”, a focal point of discussion as Nigeria heads into an election next month. President Muhammadu Buhari and the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) face a formidable challenger in former vice president Atiku Abubakar of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP).

But while the Boko Haram insurgency gets most of the international headlines it isn’t the only internal security crisis Nigeria is grappling with as it heads to the polls. There are significant pockets of insecurity in the northwest, the Middle Belt, and in the southeast. Most of these conflicts are often framed or perceived around ethnic and religious differences in a country with over 200 major ethnic groups.

The conflicts

In large parts of central Nigeria, internecine conflicts between nomadic herdsmen and farming communities have claimed hundreds of lives this year. These attacks, though at its root is a competition over land and water, risk spiraling into something larger and at one point early in 2018 had overtaken the Boko Haram crisis in number of casualties.

In northwestern Nigeria’s Zamfara state and parts of Kaduna state, marauding bands of unknown attackers swoop in on villages, leaving dozens of dead people in their wake with little clarity on the motives of these bandits.

The clash between Nigeria’s army and its Shia Muslim minority is an example of how security forces are, at times, a bigger part of the problem than the solution. It dates back to December 2015 when a clash between the army and a Shia group in the northern city of Zaria left 347 Muslims dead and their leader arrested. Since then, there have been numerous protests demanding the release of the leader. In the past two months, three of such clashes have seen about 40 people killed. A recent New York Times investigation into a clash in Abuja showed the military had used disproportionate force on the Shia protesters.

In the southeast there are clashes between communities in Ebonyi and Cross River states over land boundaries have left as many as 20 people dead. And while there is no ongoing conflict in the Niger Delta basin, there is the ever-looming economic disruption with the resurgence of militancy in Nigeria’s oil-producing region, with regular threats by some of the militant groups.

Displaced

These various conflicts have, in varying degrees, contributed to the two million people in Nigeria that have been displaced, according to the International Organization for Migration. The biggest contributors to this number are the Boko Haram conflict in the northeast and the farmer-herdsmen clashes in the Middle Belt.

This has caused a huge drop in agricultural production in the Middle Belt, regarded as Nigeria’s food basket, and accelerated the huge rural-urban drift to urban centers in the area, according to this report by political risk analysis firm, SBM Intelligence.

The worsening state of Nigeria’s internal security is likely a disappointment for the Nigerian voters who picked president Buhari, a former army general and military head of state with a solid record on dealing with conflict. Improving security was one of the two central pillars of his campaign in 2015—the other being fighting corruption, so it was generally believed Buhari would be best placed to strengthen the country’s internal security. But his government has performed below expectations.

“There are two levels of corruption within the Nigerian security sector,” explains Matthew T. Page, an associate fellow with the Africa Program at Chatham House. “There is the informal corruption where sums budgeted for security are embezzled by the political and military leadership. There is also the formal corruption comprising of security votes, an amount budgeted by federal and state governments for security and on which they do not render accounts of how it is spent.”

As Page sees it, perpetual insecurity justifies the continued increase in security votes at national and sub-national levels, which also makes a few people rich due to defense sector corruption. “The security votes also provide election funding for incumbents, giving politicians an incentive to keep a certain level of insecurity in order to justify the votes,” he said.

Overstretched

These conflicts have also strained the capacity of Nigeria’s security forces: the Nigerian Army, for example was deployed in as many as 32 of the 36 states in the country as at January 2017, battling terrorism, cattle rustling, kidnapping, communal clashes and other forms of insecurity. This is besides the deployment of other branches of the military such as the Navy predominantly in the Niger-Delta and coastal regions, and the Air Force which is also involved in the war against Boko Haram in the northeast.

A major factor for the deployment of the military internally is that Nigeria’s police, which operates a federal structure, is insufficiently staffed. There are 370,000 police officers for a population of 174 million Nigerians, which gives a ratio of about one policeman to 500 people, short of the United Nations’ recommended police-citizen ratio of one to 222. That’s a shortfall of 155,000 police officers.

A closer look at the current police numbers reveals as much as a third of the police force is dedicated to serving as personal security to VIPs and corporate organizations who pay for these services in a scheme that has been controversial and widely criticized. This is besides the fact that the police lacks sufficient training, adequate remuneration, working equipment and is widely perceived as corrupt with a tendency to use excessive force.

Another challenge with policing in Nigeria is that is disproportionately concentrated in urban centers, leaving large swathes of the rural areas without any police presence or chronically under-policed. It is no coincidence that most of the conflicts happen in rural areas.

In the absence of adequate policing in these areas, there has been a rise in vigilante groups to protect their communities against attacks. While some of these vigilante groups have been very effective in complementing the police and even the military, such as the Civilian Joint Task Force in Borno State (albeit with criticisms), others have mutated into ethnic militias, participating in sectarian violence especially across the Middle Belt.

The conflicts have also had a huge adverse effect on the Nigerian economy with the pastoral conflict having the greatest real effects. A 2016 report estimated as much as $14 billion is lost annually to clashes between farmers and herdsmen in Nigeria’s Middle Belt which is the country’s most agriculturally productive region.

“From a perception point of view, the Boko Haram crisis has an outsize effect as it places Nigeria squarely in the ambit of the Islamist uprising in the Sahel,” says Cheta Nwanze, an analyst at SBM Intelligence. “Some of these conflicts will lessen, but it is likely the Boko Haram conflict will intensify as the terrorists might seek to make use of the distraction provided by the elections to mount a major offensive,” he adds.

As the 2019 elections approach, the impact of these conflicts (and political indifference to the two main candidates) shouldn’t be underestimated. There’s a long-held belief elections in Nigeria come with the threat of violence which causes some voters to stay at home for safety. But with the ongoing violence some analysts expect lower voter turnout than in previous elections. INEC, the national electoral body, is already reporting millions of uncollected voter cards.

The government will likely deploy a large proportion of the police force for the elections, specifically at polling centers and to ensure there is no tampering with election materials and results.

The approach to dealing with these conflicts seems to be unchanged: deploying the military to flash-points, which continually stretching them beyond their capacity. Nwanze suggests this approach is counter-productive. “Our security agents have a habit of alienating the very population they are meant to serve, and as a result, providing recruits for all sorts of groups. That has to change.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox