Africa has forgotten the women leaders of its independence struggle

When the British colonial officers refused to give permits for demonstrations, activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti mobilized local market women for what she called “picnics” and festivals.

When the British colonial officers refused to give permits for demonstrations, activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti mobilized local market women for what she called “picnics” and festivals.

One of few women in early 1920s Nigeria to receive post-primary education, Ransome-Kuti used her privilege to coordinate the resistance against colonialism in Nigeria that not only targeted the British but also the local traditional figureheads they used to enforce their rules.

The Abeokuta Women’s Union, which she founded, protested unjust taxes, corruption and the lack of women’s representation in decision-making corridors. While she is probably better known now as the mother of the Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti (an activist in his own right), Ransome-Kuti’s role and years as the mother of anti-colonial activism in Nigeria are rarely celebrated outside of early primary school texts. Her son once sang: “She’s the only mother of Nigeria.”

In many ways, the muted legacy of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti in Nigeria’s independence movement plays out across the continent.

In the six decades since many African countries attained political independence, the stories of women in the liberation struggle is yet to be told and celebrated unlike their male counterparts who wasted no time in having universities, airports and major highways named for them and affixing their faces on national currencies.

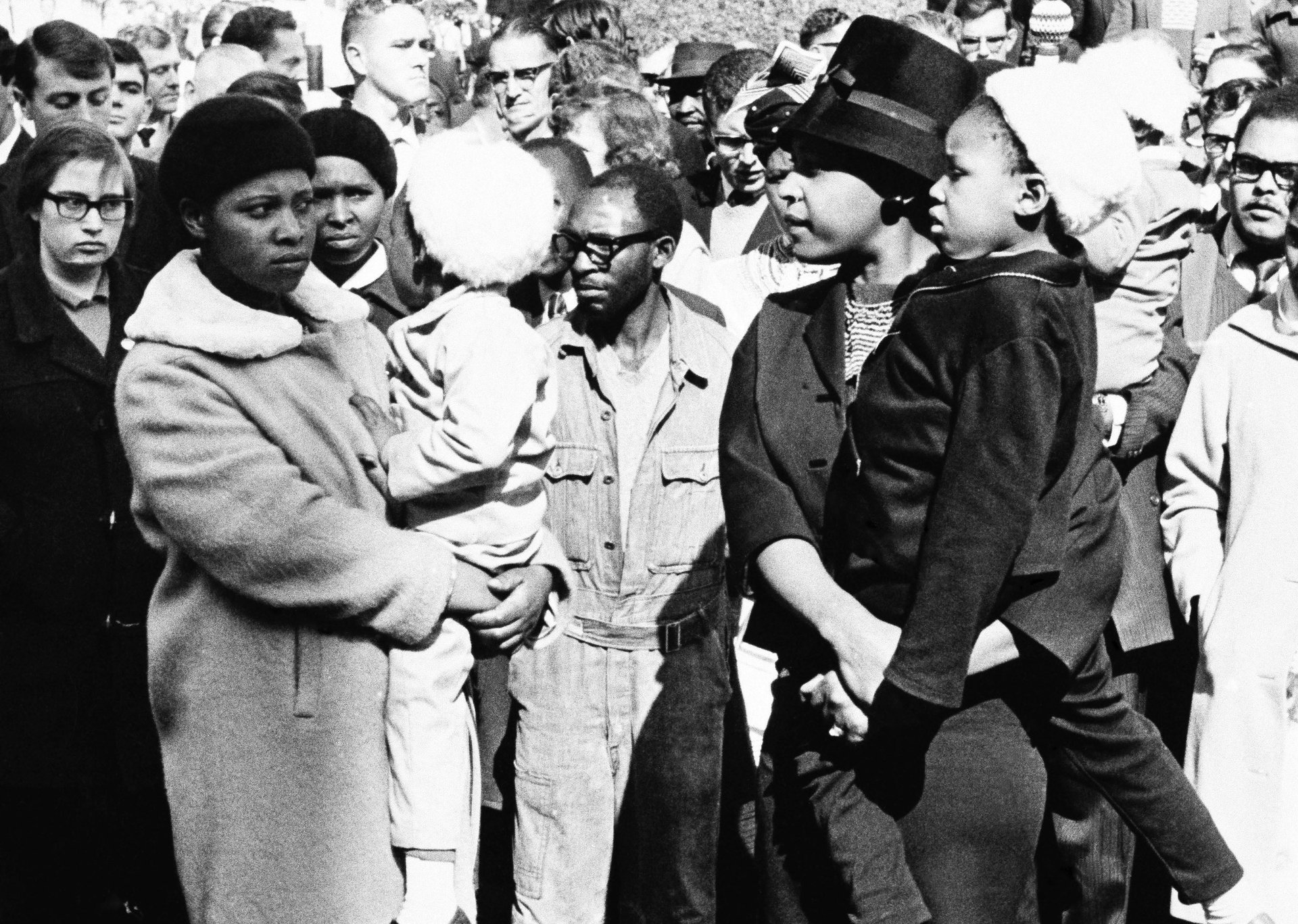

For those whose stories have been told, such as anti-apartheid activist Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, they are riddled with double standards and sexist tropes which often try to to position them as “helpers” to men and reduce them to wives.

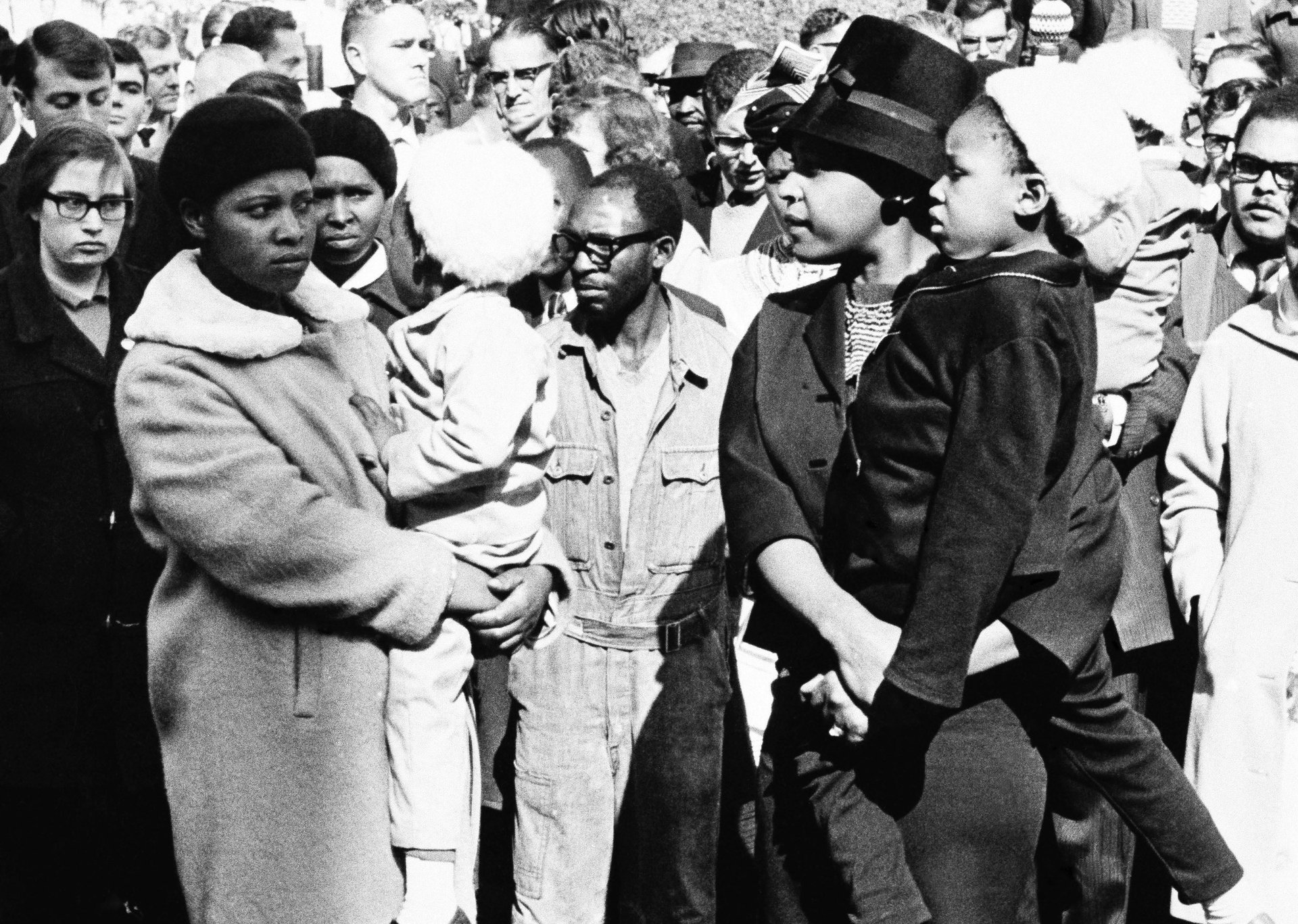

Women, both educated and uneducated, were pivotal to liberation parties, although they were often pigeonholed with the less powerful women’s wing of the party, if it had one. While they had little opportunity to be part of the broader organogram of these parties, leaders of the women’s wing were able to demonstrate enormous leadership potential.

Within a year of being recruited, Bibi Titi Mohammed, as head of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) women’s wing, had attracted 5,000 women to join. Bibi Titi used women’s cultural and economic network to mobilize, exchange information, sell party membership cards, announce rallies, organize marches, and raise money for TANU, which would go on to become the freedom party of modern Tanzania.

In Ghana, Mabel Dove-Danquah, described as a ‘trail-blazing feminist’ was well ahead of her time as an outspoken advocate for women’s equality. Dove-Danquah worked as a writer, journalist and editor for various liberation-minded newspapers including the Accra Evening News which was founded by Kwame Nkrumah. She was among a host of women Nkrumah and his Convention People’s Party used to advance the struggle for independence and would go on to become the first African woman to be elected by popular vote to parliament in 1954.

The CPP’s women’s wing were made up largely of market women who, while crisscrossing the country to buy and sell, went along with the gospel of self-determination. Just like in other African struggles, market women were also the financial backbone of the party but as Ghana commemorated 62 years of independence this month, their names and contributions have effectively been written out of popular history.

In contexts where the fight for independence took a particularly violent turn, women were also on the front lines. Young Muslim women were a central part of the FRELIMO resistance against Portuguese colonial rule in Mozambique. FRELIMO recruited teenage girls and young women as guerrilla fighters and crucially in intelligence gathering as they were seen by the Portuguese as non-threatening. They also performed domestic duties such as cooking and cleaning.

But the lack of recognition for the role of women in history telling, is not unique to Africa. Around, the world, there have been attempts to rewrite the past and make it fuller and nuanced, says professor Akosua Darkwah, head of the department of sociology at the University of Ghana. “Often because, these stories are being told by men so they tell it from their perspective,” she says, “but there has to be a constant reminder that it couldn’t have been that all the women were just sitting down watching.” In 2017, Darkwah co-authored a paper about women and post-independence African politics.

In struggle times, the leaders of African liberation spoke passionately about women’s equality and recognized their contributions. By Nkrumah’s own admission: “much of the success of the CPP has been due to efforts of women members. From the very beginning, women have been the chief field organizers. They have travelled through innumerable towns and villages in the role of propaganda secretaries and have been responsible for the most in bringing about the solidarity and cohesion of the party.”

But that progressive rhetoric was at best a veneer as they did little post-independence to structurally include women in governance and remove sexist colonial-era laws. Although his government introduced a gender quota (9%) [pdf p.3] in the legislature in 1960, Kwame Nkrumah’s cabinet as head of government and president, for example, was exclusively male for 11 out of the 14 years he governed. As the economy of newly independent Ghana found itself in dire straits, due to decades of colonialism, the Cold War and his bankrolling of other liberation movements, Nkrumah, picked on market women as a cause of the economic challenges.

Again, women were not spared the brutalities that accompanied criticism of the authoritarian governments that ruled in post-independence Africa. Shortly after independence, Bibi Titi was arrested by the government of her former ally, Julius Nyerere, on trumped-up treason charges. She was sentenced to life in prison but was released after two years on pardon and she spent the rest of her life out of public view.

Similarly, Malawi’s first female lawyer Vera Chirwa endured exile and long years of imprisonment when she along with others, fell out with president Hastings Kamuzu Banda. Chirwa is a founding member of the Malawi Congress Party, which eventually led the country to won independence. She also founded the League of Malawian Women which did not only fight for the rights of women but was a leading supporter of the resistance against white domination in Malawi.

Generations later, the power that women’s wings of political parties across the continent wielded have been decimated and usurped by first ladies. They have been depopulated of charismatic, educated, professional women to the extent that a coherent progressive feminist agenda can now be found with civil society. For example, the women’s league of the African National Congress (which has been described as “the gatekeepers of patriarchy”) until 2017 maintained South Africa was not ready for a woman president, despite the party possessing a cadre of accomplished women politicians. Tellingly, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf remains Africa’s only elected female president.

There are many untold stories of women’s role in the resistance against European colonialism from the women at the frontlines in Algeria and Zimbabwe to the Somali women poets whose words captivated and inspired their freedom movement. However, a new generation of African feminists are determined to reclaim these narratives.

In Lusaka, Zambia, the Museum of Women’s History has collected 5,000 pieces of audio records and other artifacts and is already changing the narrative about women and equality, which was nearly erased by colonialism. Similarly, tech savvy feminists are using the occasion of Ghana heritage month to reposition women’s role in the history.

But professor Darkwah cautions: “That is not the job for only feminists…this is our history, this is a more complete rendering of our past, it shouldn’t be the responsibility of only young feminists to tell us that. It should be all of us.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox