A new investigation by anti-corruption NGO Global Witness has discovered the apparent theft of more than $50 million in public funds from the Republic of Congo by Denis Christel “Kiki” Sassou-Nguesso, son of the country’s president, Denis Sassou-Nguesso. The resulting report alleges the younger Sassou-Nguesso, 44, laundered the money through a “complex and opaque corporate structure” spanning six European countries, the British Virgin Islands, and the US state of Delaware.

It’s far from the first time the nation’s first family has been accused of embezzling funds from their country’s treasury. In 2007, Global Witness fingered Kiki, a Congolese parliamentarian, as having spent “hundreds of thousands of dollars of money that may derive from sales of state oil on lavish designer shopping sprees in Paris, Marbella and Dubai.”

His sister, Claudia Sassou-Nguesso—also an elected member of Congo’s parliament—allegedly pilfered nearly $20 million in state monies to buy a condo in New York City’s Trump International Hotel & Tower, according to a Global Witness report released in April. (The Congolese government called the charges “fake news.”)

The latest findings shed further light on what Global Witness calls “loopholes in the anti-money laundering framework” of the European Union, United Kingdom, and the United States, all widely considered to be among the world’s strictest jurisdictions. That, plus structural deficiencies in the global financial system, are “helping enable kleptocratic elites to move their dirty money with no questions asked.”

The “grand-scale corruption” in which Global Witness says the Sassou-Nguesso family continues to engage has a “devastating human impact” in a country that is sub-Saharan Africa’s third-largest oil producer but where the average yearly income is equivalent to $1,640 US dollars (when people actually receive their wages) and one-third of the population lives below the poverty line.

“All of the jurisdictions involved urgently need to address the ways in which shell companies can move funds around at ease, facing no tough questions on provenance or legitimacy despite multiple corruption warning signs,” Global Witness said in a statement calling for requirements that would force shell companies to disclose the names of their true owners.

President Sassou-Nguesso, 76, has been ruled the the central African country, sometimes called ‘Little Congo’, for a combined total of 35 years. He first came to power in 1979 and led the country until 1992. He returned to office in 1997 and has remained there since.

How to hide a small fortune

The Sassou-Nguesso investigation took more than a year, Global Witness lead investigator Mariana Abreu told Quartz. She said she connected the dots using financial statements, corporate filings, and “secret contracts” from sources in numerous countries. It’s very unusual to obtain concrete evidence of this type of wrongdoing, said Abreu.

Here’s how the alleged scheme reportedly worked:

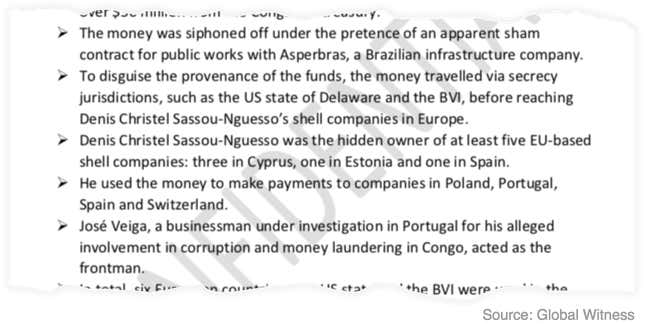

Kiki Sassou-Nguesso was the hidden owner of at least five European shell companies located in Cyprus, Estonia, and Spain, according to documents reportedly seen by Global Witness. These companies were fronted by Portuguese businessman José Veiga, who is currently under investigation by authorities in Portugal for corruption and money laundering. The companies were incorporated in Cyprus, under Veiga’s name, says the Global Witness report. However, ownership of the companies had already been transferred to Kiki in a secret transaction executed by a Brazzaville notary.

Veiga was also the middleman in Congo for a Brazilian company called Asperbras, which Global Witness says was awarded an “apparent sham contract for public works” by the Congolese government in 2013. This included such projects as a supposed geological survey.

Asperbras deliberately inflated its fees by $50 million, a sum Global Witness says was later diverted to the companies secretly owned by Kiki Sassou-Nguesso, citing a report from French newspaper Le Canard Enchaîné. The money was first routed through “secrecy jurisdictions” like Delaware and the British Virgin Islands before being sent on to the EU, claims the Global Witness investigation.

Asperbras “completely refuted any claim of overpriced contracts and irregularities in the Congolese public procurement process,” and said it “did not know anything about deals closed by Veiga or his companies,” according to Global Witness. The group says it did not receive “substantive responses” to requests for comment from Kiki Sassou-Nguesso, an attorney for José Veiga, or the Congolese government.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox