What does the future hold for China’s Africa project?

These four leading voices on China-Africa matters in the 21st century agreed to discuss with Quartz Africa how they each see the relationship between African countries and China evolving over the coming years. Each person has a perspective that not only helps highlight some of the more pressing issues but also contextualizes where things are headed. All answers were edited for length and format.

These four leading voices on China-Africa matters in the 21st century agreed to discuss with Quartz Africa how they each see the relationship between African countries and China evolving over the coming years. Each person has a perspective that not only helps highlight some of the more pressing issues but also contextualizes where things are headed. All answers were edited for length and format.

Cheng Cheng: chief economist of the Made in Africa Initiative, a Chinese-backed initiative to help African countries capture opportunities of industrialization.

W. Gyude Moore: visiting fellow at the Center for Global Development and former minister of public works in Liberia.

Hannah Ryder: chief executive of Development Reimagined, a development consultancy based in Beijing and former head of policy and partnerships for UNDP in China.

Cobus van Staden: senior researcher of China-Africa relations at the South African Institute of International Affairs, and the co-host of the China in Africa Podcast.

1. China-Africa relations have so far remained a two-way affair in which both sides adapt to popular perceptions and policy proposals coming from the other side. How do you think this relationship will remain or change in the coming years?

W. Gyude Moore: “The relationship is already changing. China’s growing power and influence has reached near-peer status with the US. It invites scrutiny that was nonexistent when the China-Africa relationship began. With power comes responsibility, so Chinese activity in Africa, especially regarding lending and environmental sustainability is now changing—for the better. There will be growing pains for both parties: China will have to cut losses on non-performing loans to projects that were never viable from the beginning.

African states may be left with half-completed projects as China attempts to cut its losses. There will also be a convergence in standards of project selection and execution between China and other institutional lenders. China will increasingly become more like traditional Western development finance bodies less than its former self.”

Cobus van Staden: “I think the two-way street aspect of the relationship will probably continue, because at present it is still mostly made up of bilateral relationships between governments. However, the continued implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), and proposed reforms at the African Union could give Africa new platforms to negotiate more collectively. However, I expect these changes to happen quite slowly, and it remains to be seen whether they’ll really change the relationship.”

Cheng Cheng: “I think the interaction mode will remain two-way approach in the future. In the cooperation between China and Africa, Beijing has established a request-based, project-selection process since 1950s, in which African countries would inform China which projects they want the most, then China would decide among the projects which ones to support based on project sustainability and China’s own ability limit. The Forum for China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) has enforced the request based model as a multinational mechanism since 2000. I don’t see reasons for major changes of the policy.”

2. China’s investments and funds allocations in Africa has traditionally focused on resource-rich and larger economies, but are there other smaller African economies we should be watching for in the coming years?

Hannah Ryder: “Given that 40 African countries have now signed MOUs on the Belt and Road Initiative, coupled with the fact that the BRI is currently focused on infrastructure investment, but is also trying to improve sustainability, we can expect grants and loans to be both a) smaller and distributed more broadly/evenly across the continent; and b) more regional in nature rather than one-country focused. Indeed, such projects in Africa have seen a decline in value since 2016. Although African countries do need huge new external funds from all development partners including China, we can’t expect a big increase from China overall, since China’s 2018 FOCAC pledge kept the amounts for grants, loans and credit lines from 2018-2021 basically the same as its 2015-2018 pledge.

On the other hand, the data on China’s investment—which I define here as foreign direct investment—is available from China and the UN broken down by country up to 2014 and can therefore be better understood. The data suggests that in the past, China’s FDI flowed to countries either have relatively strong/reliable business environments like South Africa, or large assets like Nigeria and Zambia, but it has diversified considerably since then to flow to others with better business environments. Since 2014, we also know anecdotally that FDI is now starting to flow into countries such as Ethiopia, who are actively promoting manufacturing and have access to zero-tariff treatment for their exports, and trying to attract Chinese factories to set-up there.

For FDI, we should therefore be looking at two sets of countries—those like Nigeria who are large and fast-growing and their business environments are improving (even if a little risky), and those such as Rwanda and Senegal—those who are trying the same techniques as Ethiopia, and whose business environments are also improving. We have already seen Chinese FDI into pure assets slow down, as these are increasingly showing themselves harder to manage (e.g. reputational risks around mines, etc).”

WGM: “I am not as optimistic that there are dark horses among the smaller countries that would suddenly be attractive to Chinese lending. Unless they are endowed with significant natural resources that are in high demand, small African countries present unique challenges to all investors—Chinese or otherwise. They have very small market size (for businesses that require scale), outside infrastructure, the ticket size for deals is smaller than in the larger markets. High transaction costs will continue to limit what’s possible.

Crucially, there aren’t that many small countries with superior infrastructure and regulatory system (I can think of two—Botswana and Mauritius) that they could offer as a competitive edge. We might see more Chinese investment in places where they aren’t as big now as the investment becomes more private sector driven—Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal seem like they would benefit from this.”

3. Most of the Chinese investment in Africa is led by transport infrastructure, energy, and minerals. What others sectors will Beijing and private Chinese investors noticeably increase spending over the next decade?

CC: “Firstly, China’s investments in Africa are not concentrated on infrastructure or mining. This is a common misreading. A very large amount of Chinese investments to Africa are in manufacturing, usually in the way of special economic zones. Those big infrastructures, most of them are EPC (engineering, procurement and construction) projects, some times with Chinese finance. But the Chinese or China do not own the projects.

Second, Chinese tech giants like Alibaba have been very active in counties like Rwanda, Kenya and Nigeria, together with Chinese venture capital and private equity funds. And Chinese companies have been investing in manufacturing in better-performing markets in West Africa, such as Senegal, Ivory Coast and Ghana.

Finally, since China is moving to becoming a high-income country in the next five to eight years, the market has been naturally channeling investments into agriculture and agro-processing sectors. China is transforming into the single biggest market ever existing on the planet. This is going to shape production chain of most consumer goods, especially high value adding food.”

HR: “We can expect to see two trends into the future. First, a trend towards public-private partnerships around Chinese-built infrastructure projects. This will kill several birds with one stone – it will bring down the amount that national governments need to borrow to finance new infrastructure (whether justified or not they are coming under a lot of flak for too much debt) and it will increase the amount of investment that comes from China, which may well increase investment from other richer countries too.

Second, and linked to the first trend, a trend to increase and diversify types of investment from China. We will see more real estate investment, more factories in sectors beyond assembly and textiles/apparel, and FDI into a wider set of countries.”

WGM: “Infrastructure will continue to be attractive simply because of the size of the gap in Africa and China’s large excess capacity in this sector. So both energy and transport infrastructure will remain a big draw for China-Africa cooperation. But I think we will begin to see Chinese investment in agriculture too—especially the use of technology to increase productivity in agriculture.

Obviously, a huge barrier to investment in agriculture is the question of land tenure and that’s an Africa problem to fix to make agriculture attractive.”

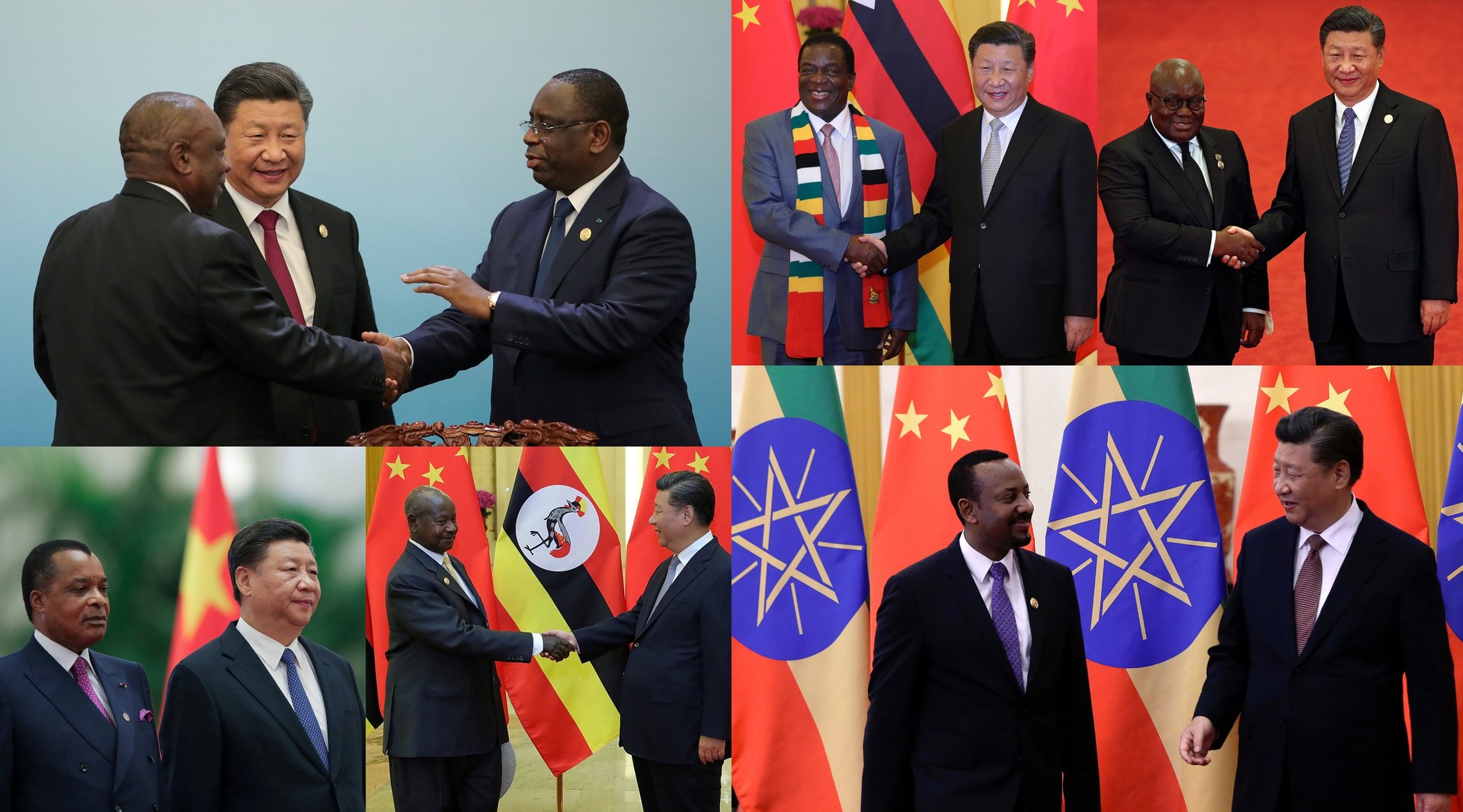

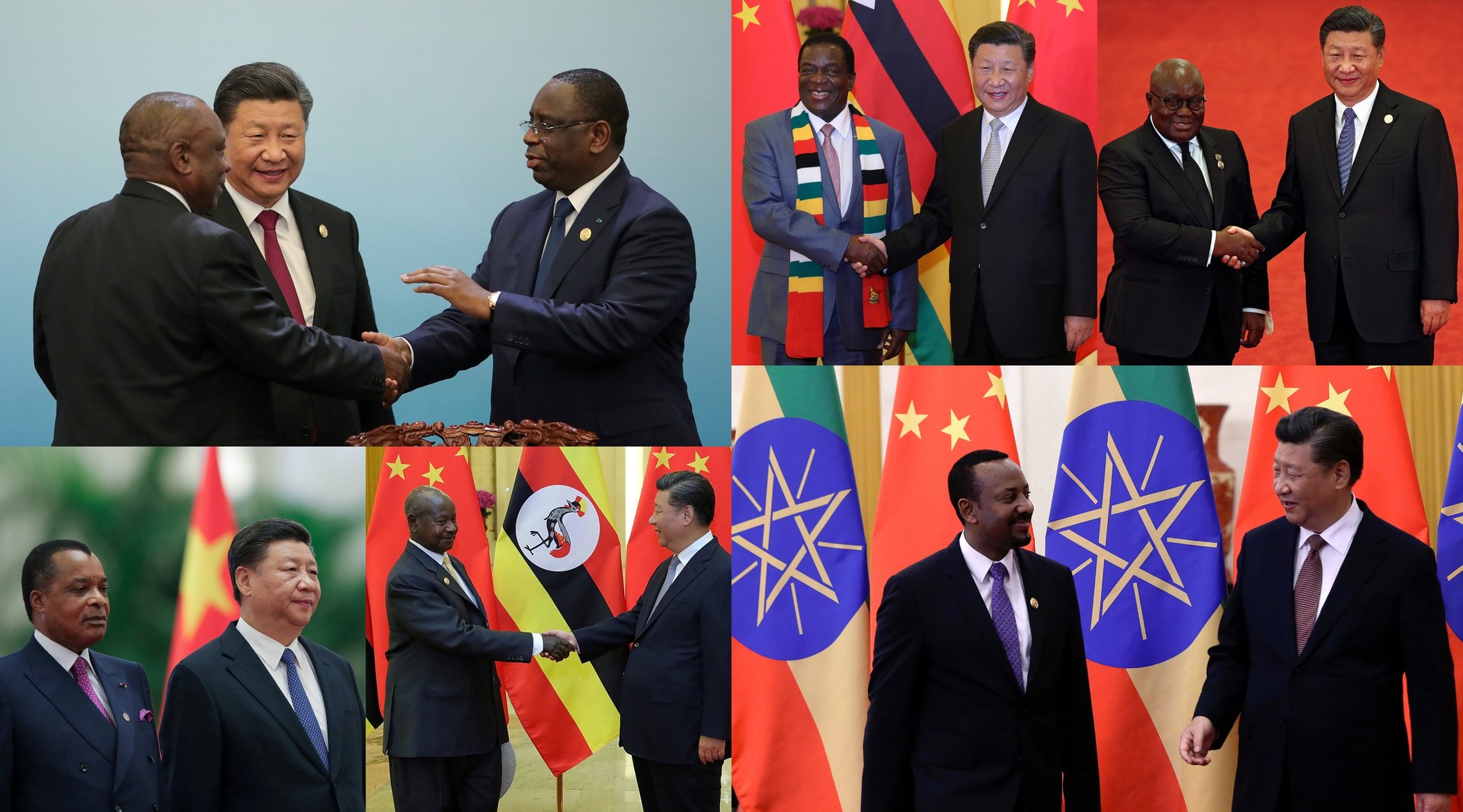

4. As president Xi Jinping oversees an ascendant China, how do you think his leadership will impact China-Africa relations compared to Chinese leaders from the past decades?

WGM: “The Communist Party (CCP) retains power regardless of who’s the leader and Chinese engagement with Africa is not simply driven by trade and commerce, it is also political. So things will remain the same. However, we can expect to see some changes and it is, as yet, unclear what it means for Africa. Under Xi Jinping, China has become more assertive in defining and protecting its sphere of influence. We have seen this in the east and south China seas and in the trade war with the United States. Chinese response to criticism or perceived slight in Australia, Canada and India has been more muscular than before.

As China’s power increases, it is not inconceivable to begin to notice a change in China’s approach in Africa. At risk would be countries exposed to China either as a market or as a creditor. China is the largest bilateral creditor for a number of African countries.”

CvS: “President Xi has used some of his personal political influence to promote initiatives that directly impact Africa. Two notable examples are the Belt and Road Initiative and his pronouncements against vanity projects. Both of these could impact the nature and scale of Chinese initiatives in Africa.

I think while his personal style and preoccupations will have direct bearing on China-Africa relations, he also prioritizes the CCP’s centrality in all China’s external relations. So while he might bring some uncertainties, he also ensures a certain level of institutional stability which has underlain the China-Africa relationship for decades. I think the real question is how the relationship will shift as president Xi deals with economic changes at home.”

5. By expanding its military footprint in Africa, China is helping secure its interests abroad and striving to project itself as a responsible global power. How do you think Beijing’s defense engagements will impact its foreign policy objectives in the coming decades?

CvS: “At present, China’s expanded military footprint, while notable, has remained relatively contained. The establishment of its first overseas military base in Djibouti was, of course, a big shift, but we have not so far seen a rapid ratcheting up of military engagements in Africa. So far, these have largely been under the auspices of multilateral initiatives under the United Nations.

That said, it has also gained the Chinese military foreign experience and additional capability. It seems aimed at building greater international capability for the Chinese military without (so far) giving many clues about how that capability might be used. At present, it is a wait and see game—not only to see what China will do, but how other regional and global powers will react.”

6. How do you think Beijing’s “no-strings-attached” approach to loan provisions will change—particularly in light of president Xi reiterating that China wasn’t spending funds on “vanity projects”?

HR: “The international system for loans is currently dysfunctional, but too much debt from China is not the problem—it’s too little debt from others. China has three major rules around its loans to other countries: 1) It does not give loans to countries that recognize Taiwan; 2) it only gives loans for projects it assesses will provide a return; 3) It does not—except through the newly created Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank—give loans for projects that will be completed or overseen by non-Chinese firms.

The rules used by institutions like the World Bank or African Development Bank (AfDB) are different. For example, they require in-depth, third-party social and environmental impact assessments, meaning decisions take a long time, in some cases years. Their loans also tend to go to a narrow set of countries, because their major donors such as the UK and US find it hard to justify giving or lending money to middle-income countries, countries with high existing debt levels or countries with poor human rights records.

The current pressure from major donors is for China to become more like the World Bank and introduce more rules and restrict the countries it lends to. China seems to be acquiescing. Its new “Belt and Road debt sustainability framework” has a very similar methodology to that used by the IMF and World Bank to assess if a country has a debt problem.

However, while environmental and social impact assessments are critical, the World Bank and others need reform too. They could learn from China how to assess infrastructure projects and feasibility in order to disburse more widely and faster. China itself could do better—especially by loosening its rules around allowing the projects it funds to be done by non-Chinese actors.

Loans are critical for African countries to meet the UN sustainable development goals. The AfDB estimates continental infrastructure costs that can’t be met by internal funds to be least $63 billion per year. The international community should be working on opening up the market for loans not trying to close a major source down.”

CC: “Actually, China has always been strict with the financial and economic feasibility of supported projects in Africa. But China would not have non-economic conditions to be attached with Chinese projects, for it would go against the very basis of Chinese philosophy. Even for Africa countries, I do not see any reason for the non-intervention policy to change. For 60 years or longer, donor counties have provided over $1 trillion worth of projects in Africa, all with strings, and Africa did not really develop much with these projects. So why would Africa ask China to do so?

No matter how smart development experts think they are, it is African governments that will lead their countries ahead, not these foreign projects, for most of them only last for five to eight years. If African governments are not trustworthy, then who else?”

CvS: China is already bringing in new mechanisms to verify the viability and impact of Chinese project financing in the global south, and these could come to challenge the ‘no-strings’ narrative. China is becoming more risk-averse about lending due to economic changes at home, as well as in response to debt-trap criticism from Africa and elsewhere.

(Some) African governments will likely also face more scrutiny at home about new Chinese projects, due to perceptions that these deals fuel corruption. The recent pausing of the Standard Gauge Railway in Kenya could indicate that Chinese financing might be harder to get in the future.

7. What role will soft power play in deepening China’s engagement in Africa?

HR: “In October 2018, data collected by my firm Development Reimagined and released exclusively with Quartz revealed that 48 Confucius institutes have sprung up on the African continent, from zero in 2000. We put this in context and contrasted this to other educational and cultural institutes—such as French Institutes, which have a much larger established presence on the continent but have seen slower recent growth.

There is little other continent-wide statistical analysis of China’s soft power tools—from student scholarships to media outlets to museums, let alone comparison to the same or similar tools of other “global powers.” But it is likely that we would see similar trends to that which we have seen for the Confucius Institutes for other soft power tools since 2000, since many of these tools are mentioned in FOCAC commitments, and target numbers have ratcheted up over the years. And the types of tools are expanding. In 2019, we saw the first African museum being built with a Chinese grant (in Senegal).

That said, getting results from soft power is not about quantity. It’s about quality. Quantity matters to establish visibility. But if the Chinese government is to persuade African citizens that it understands and is working towards their needs and perspectives (which is essentially what soft power aims to do), investing in and driving up quality is crucial. Right now, Chinese stakeholders are finding it hard to invest and drive up quality in China let alone globally. So this will take some time.”

WGM: “I am unsure that the answer here is an unqualified “yes.” China’s lack of colonial history in Africa is a plus in that China faces no historical resentment. But for soft power attraction, it is a weakness. Language is an issue. Portugal is too poor to be of much economic help to its former colonies—but Angolans, Brazilians, Sao Tomeans, Mozambicans are still drawn to Portugal. I think China faces significant headwinds to being independently attractive on the basis of culture and values alone.

I see Beijing pushing education and the arts. We see this in the spread of Confucius Institutes and ever-expanding scholarship opportunities for Africans to study in China. Whether it’s doing voiceovers for Chinese content in African languages or producing content meant for African consumption, we can expect to see more investment in the arts.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox