Hello Quartz readers,

Last week we asked how you’re holding up, and while we expected a lot of “I haven’t worn pants in a month,” what we got was more “Actually I make my own pants now.” Quartz readers never fail to impress.

If there’s one theme to your replies, it’s the importance of adaptation. Reader Lee set up an exercise/yoga space in her office, where she burns incense and plays relaxing music all day. Sarah is attending topical webinars to keep her mind fresh while she reads up on vaccine research. Denis is focusing his remote workday on tasks completed instead of hours spent at his computer. Everyone is feeling anxious, and everyone is trying to keep it together for themselves, their family, or their colleagues. So keep helping each other out:

Okay, let’s get started.

Cracking the codes

QR codes (short for “Quick Response” codes) got their start in 1994, in the Japanese labs of a Toyota subsidiary named Denso Wave. The automaker needed an easy way to keep track of car parts on the assembly line, and the QR code offered a clear improvement over the 50s-era barcode. By storing information in a two-dimensional field of squares instead of one-dimensional lines, QR codes can hold about 100 times more data (enough storage space, in fact, to fit a simple version of the game Snake).

The codes stuck to industrial applications until 2010, when smartphones finally gained the ability to read them and translate them into web links. A wave of hype followed, predicting that QR codes would open a portal between the physical and digital worlds—augmented reality. Eager to position themselves as tech-savvy, companies began plastering squares on advertisements, buildings, and employee uniforms, urging consumers to scan them.

The only problem was, QR codes sucked. In those early days, smartphone users had to download a bespoke app to scan them, data connections weren’t as widespread or reliable as they are today, and when the site finally loaded, it was often just the desktop version of a company’s homepage, which looked terrible on a phone. Although the technology was catching on in China, by the end of 2011, comScore reported that just 20% of US smartphone users, 16% of Canadians, and 12% of Spaniards and Brits had used QR codes.

Fast forward 10 years, and coronavirus is finally giving the humble QR code its due. Reopened restaurants have replaced paper menus with QR codes (and used the digital patterns to rescue soda machines). PayPal and Venmo rolled out a touchless payment option for businesses powered by QR codes, and CVS quickly announced plans to roll them out at 8,200 stores by the end of the year. Pharmaceutical companies are even developing Covid-19 testing apps that display users’ health status via QR codes, which could determine whether they can go back to work, walk into a building, or board a plane.

At the crest of this Covid-induced wave, prognosticators are once again predicting that QR codes have finally arrived, for good this time. While it remains to be seen whether companies will find better uses for them or if consumers will lose interest after the pandemic passes, smartphones, web design, and cellular data have certainly advanced far beyond where they were when QR codes disastrously debuted to the public in 2010. Maybe this really is their moment.

Vaccine and heard

“These vaccine studies are the first time I’ve seen them requiring us to match our racial makeup to our county where we’re located. It hasn’t been in the forefront of people’s minds because for us, patients are patients and it’s more about what medical condition you have.” —Matt Maxwell, chief executive officer of Accel Clinical Services, a private clinic that runs trials in Georgia, Florida, and Alabama

The novel coronavirus has disproportionately affected Black, Latinx, and Native American communities within the US, yet the early stages of recruitment for vaccine trials saw overwhelmingly white participants. That homogeneity is a major obstacle for the testing, approval, and potential use of a vaccine. Olivia Goldhill dives into why addressing those longstanding biases is critical to conducting any high-quality vaccine study.

Deep breath

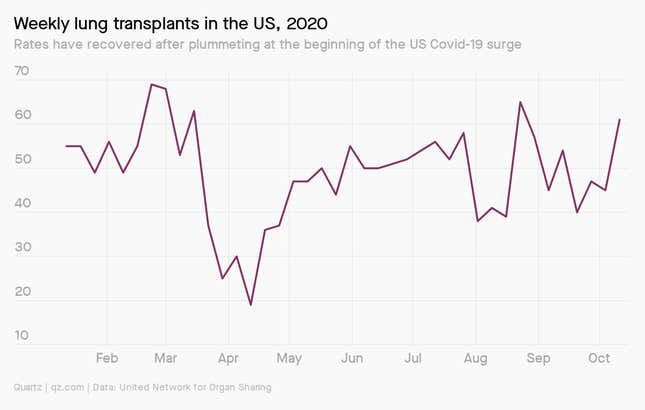

Back in March, surgeons were at a loss: They had no idea if lung transplants would be a safe option for dealing with Covid-19. Since then, there have been at least a dozen double-lung transplants for people with severe cases, along with several single-lung transplants.

“Now that more patient data has come out, we have a fairly good idea of how we can possibly approach this,” Sadia Shah, a critical care pulmonologist, told Quartz’s Katherine Ellen Foley. Doctors are beginning to compile criteria to consider when a Covid-19 patient needs a lung transplant, and to optimize the chance of recovery after surgery.

The thing about lungs is that when they’re working well, we barely notice them. It’s only when they’re threatened by something like a global respiratory pandemic that we start to notice just how talented these organs actually are. To join our Breathing Appreciation Fan Club, check out this week’s lungs obsession, then sign up for the weekly obsession email experience.

You’ve got a lot of chart

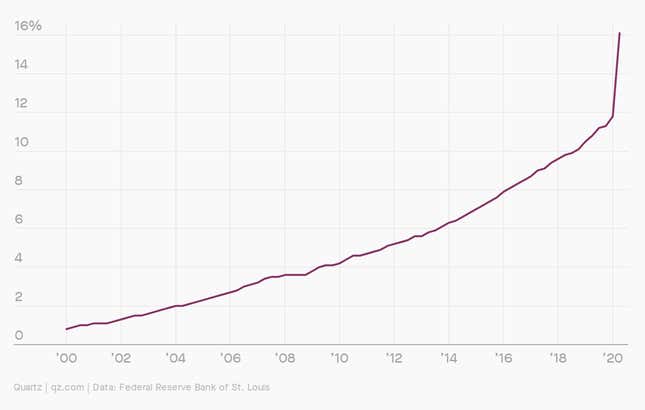

Pop quiz: What is this chart showing? Answer at the end of the email.

Easy on the ears

Coronavirus may not have changed the overall trajectory of podcasting, but it does seem to be affecting what people actually listen to. Overall podcast downloads by US listeners grew by 42% from October 2019 to October 2020, yet there was a major disparity across genres:

- News shows like the New York Times’ “The Daily” and Vox’s “Today, Explained” have seen huge jumps in downloads.

- Science podcasts are also having a moment, with 44% growth in downloads between October 2019 and 2020.

- The hardest hit genre has been “true crime.” The category grew 25% in from October 2019 to February 2020, but has seen no growth since March.

In this week’s field guide to the podcast business, we look at how podcasting has grown from a quirky peer-to-peer medium, reminiscent of the early internet, to the future of digital audio. That means examining how Spotify is shaping the next era of podcasting, why film studios are using podcasts to decide which movies to make, and how the podcast industry is failing the deaf and hard of hearing community.

*switches into a soothing baritone* With a Quartz membership, you can enjoy all of our field guides, articles, and presentations without that pesky paywall. To take 20% off your first year of membership, head over to qz.com/subscribe and use the discount code QZTWENTY. That’s QZ dot com slash subscribe, and discount code Q-Z-T-W-E-N-T-Y.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 40.6 million confirmed cases; 27.8 million classified as “recovered.”

- Box office battle: Japan’s box office is breaking records while Hollywood stalls.

- Filling the vacuum: Stuck at home, Indians are upgrading their appliances.

- Trace evidence: Can rapid antigen tests fix contact tracing in the US?

- Chewing through the cord: Disney is a streaming company now.

What about that chart? It shows e-commerce’s share of all sales in the US. From 2010 to 2019, e-commerce’s share of US spending grew from 4% to 12%, about a one percentage point increase each year. Then Covid-19 happened. From the first quarter of 2020 to the second, the US Census found e-commerce increased from 11.8% of all sales to 16.1%. So in just one quarter, e-commerce grew as much as it had in the past four years.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at needtoknow@qz.com, and live your best Quartz life by downloading our iOS app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Nicolas Rivero, Olivia Goldhill, Katherine Ellen Foley, Dan Kopf, and Kira Bindrim.