Thrifty shades of gray

Hi Quartz readers,

Hi Quartz readers,

To understand the changing habits of Chinese consumers, it’s helpful to read spending-related conversations on Douban, a popular Chinese social media platform. Here people discuss whether it’s shameful to buy leftover cakes, or how to save money by switching from disposable tampons to reusable menstrual cups. As the pandemic ravaged the economy and disrupted lives, a group named “Have you downgraded consumption today?” saw its users double, to 300,000.

“I lived from paycheck to paycheck for the four years since I graduated from university…but the pandemic has given me a thorough sense of crisis,” wrote one user. “So in 2020 I paid off all my credit card debt [and] removed all the bags I wanted to buy from my shopping list.”

For years, China has been trying to shift away from an export- and infrastructure-driven economic model towards one focused more on domestic spending. But the conversations on Douban are further evidence of a troubling trend for policy makers: Consumers are becoming more thrifty.

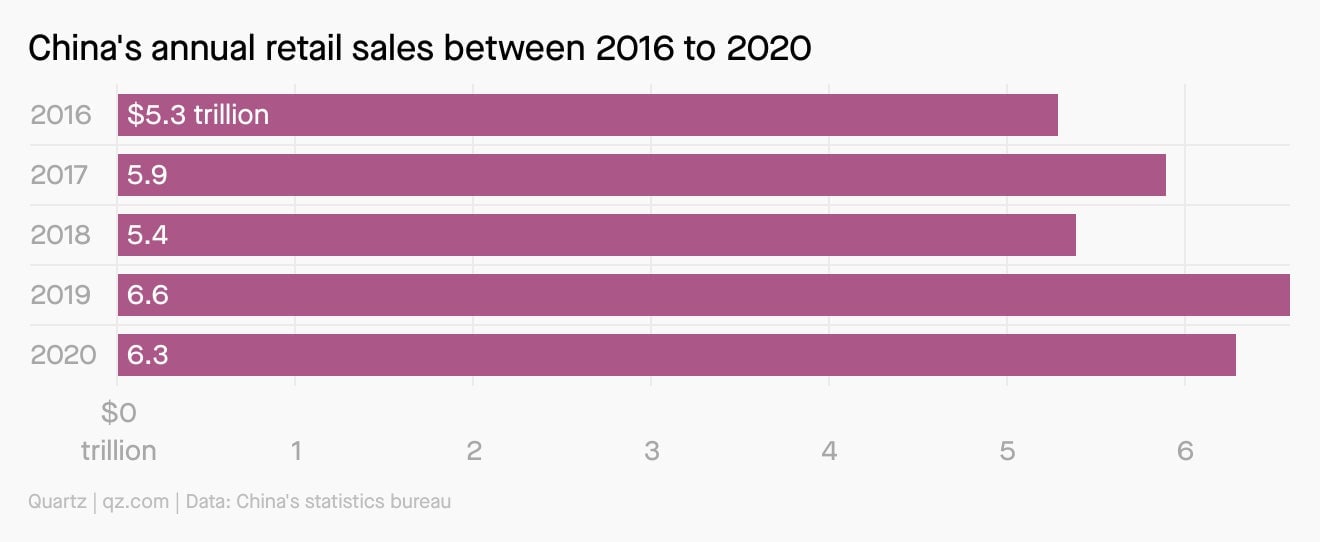

To be sure, China has achieved substantial progress in growing its consumer power. In 2020, the country’s total retail sales reached around 39 trillion yuan ($6.3 trillion), compared with $4.4 trillion for the US that year. But consumer spending is still a declining contributor to China’s GDP, and the country’s national income is increasingly allocated towards the government instead of households.

In recent months, Covid-19 outbreaks, plunging market returns, layoffs, and power crunches have also forced Chinese consumers to reassess their once rosy outlook, and reduce their spending. That’s already showing in economic data: Online and physical retail sales expanded by 4.4% in September, but the pace of growth remains lower than an average of 8% pre-pandemic.

Even young people, previously among the most free-spending consumers, are thinking more carefully about their wallets. As Cheng Shi, an economist at ICBC International Securities, wrote in a recent note (link in Chinese): “Such changed spending habits and trends won’t end with the ending of the pandemic.” —Jane Li

Check, please!

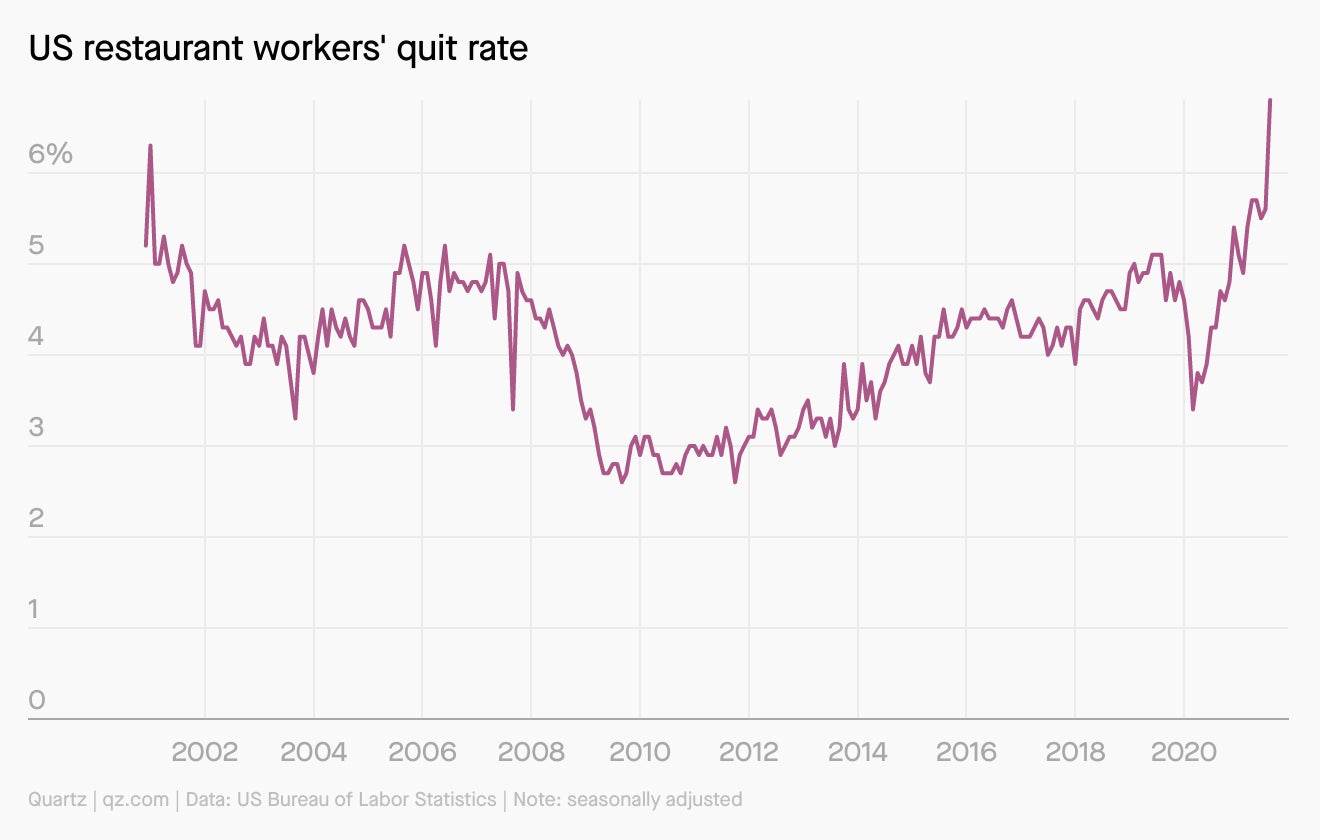

Endless breadsticks? Sure. Endless patience? No longer. Nearly 7% of workers in the US food service and lodging industry quit their jobs in August, outpacing the 2.9% rate for the rest of the economy. That marks the highest rate on record in at least 20 years.

Workers are quitting because of low pay, a desire for a new career, a lack of benefits, long hours, and potential exposure to Covid-19. Meanwhile, delivery companies are learning that the key to their long-term success is keeping restaurants happy.

Talking points

🚦 The US will reopen its borders on Nov. 8. Travelers from 33 countries can enter with proof of vaccination and a negative Covid-19 test taken within three days of departure.

📋 Traveling to the UK is a design nightmare. Complaints are mounting about the UK’s discombobulating passenger locator form, which is required for contact tracing.

📈 Joe Biden’s spending isn’t unusual. Increasing US federal spending by about 2% of GDP over 2019 would put the country on par with the UK, Poland, and the Netherlands.

🚢 The Port of Los Angeles doubled its hours. But moving cargo off container ships 24/7 actually just kicks the can down the road—er, chain. There still aren’t enough truckers.

🔗 Supply chain struggles are sticking around. That’s because consumer demand remains strong: US retail sales rose 0.7% in September, beating forecasts of a delta-induced decline.

✦ Where is that furniture you ordered? Shipping strains, labor shortages, and shifts in demand are leading to shortages of everything from cars to chicken wings. Learn more in this week’s field guide to the everything shortage. (Not a Quartz member? Try it for free today.)

Words of wisdom

“The manifest injustice of appointing someone with no experience of Africa, previously in charge of a failed Covid response, over someone from Africa, with excellent qualifications and experience…tells us all we need to know about such appointments, and the continuing marginalization of Africa in global politics, policy, and leadership.” —Michael Jennings, a researcher in international development at SOAS, University of London

Matt Hancock, the former UK health secretary who was ousted earlier this year after an affair with an aide, was on Oct. 12 named the United Nations’ special envoy for Covid recovery in Africa. Following swift backlash, the international body on Oct. 15 said nevermind.

Where’s the (affordable) beef?

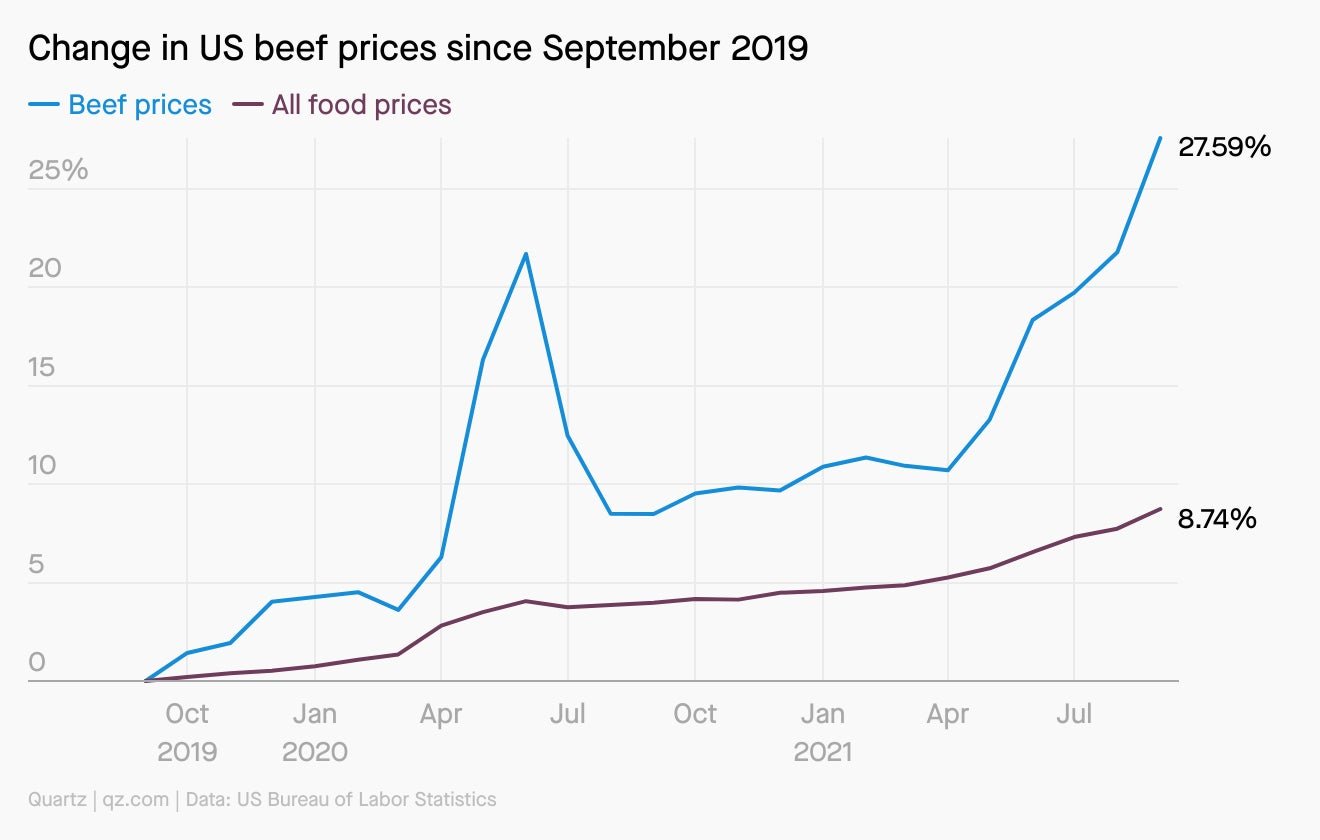

In the past year, the US consumer price index for food rose 0.9%, while the index for beef rose a whopping 17.6%. What’s the deal?

Beef prices were already on the rise before the pandemic, thanks to droughts and industry consolidation. Then Covid-19 outbreaks forced meatpacking facilities to shut down, reducing production. Those facilities never entirely recovered, and are now being impacted by labor shortages and higher freight rates.

“Anytime you see price increases like that, it’s never one thing, it’s always a stack of things,” says Peter Bolstorff, an executive at the Association for Supply Chain Management. “[When] these prices go up that fast…usually it’s because you’ve got demand shocks and supply shocks stacking on themselves at the same time.”

Elsewhere on Quartz

- Just asking: What happens if China’s growth slows down?

- IPO my: 2021 is shattering records for startup funding

- Social distancing: Xi Jinping still refuses to leave China

- In the futures: The SEC is okaying a bitcoin ETF

- Just say yes: Why rejection stings for internal job applicants

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our iOS app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Jane Li, Maxine Betteridge-Moes, Michelle Cheng, and Kira Bindrim.