Tools of the trade

To modern workers everywhere,

To modern workers everywhere,

First came email. Then came Slack. Now a new class of software is joining the quest to tackle a problem that technology alone cannot solve: getting humans to communicate efficiently.

Notejoy, for example, makes software for taking notes and sharing them with colleagues. The notes are meant to be informal and easy to search, giving anyone in an organization quick access to their coworkers’ knowledge. “If you’ve ever tried to search email or Slack, you know how terrible it is,” says Notejoy CEO Sachin Rekhi. Important information is “actually trapped in these communication tools that are terrible for knowledge sharing.”

Ironically, Rekhi is making the exact same argument about the perils of Slack in 2021 that Slack made about the perils of email in 2013. Like Rekhi, Slack founder Stewart Butterfield, likes to say that email “is a terrible way to manage internal communications,” because it keeps institutional information sequestered in a zillion individual inboxes.

New collaboration tools can be helpful, but they won’t necessarily spur humans to engage in the kind of self-reflection and healthy team norms that are essential for good communication. They can even exacerbate the communication problem by multiplying the number of channels where workers interact with one another. “Inevitably, the more we use [a new tool] the more overwhelming it’s going to feel, because nowhere in this are we actually reducing the amount of communication or becoming more efficient or strategic about how and when we communicate,” says Melissa Mazmanian, an associate professor of both management and computer science at the University of California, Irvine. “We’re just adding more and more. And so it’s not surprising to me at all that we’re going to think the tool is broken or needs to be fixed.”

Rekhi, for his part, recognizes the parallels between Notejoy’s pitch and the pitch Slack made a few years earlier. “That’s the story of technology,” he says. “You’re going to see disruption that looks at what’s already out there and invents a better way and really tries to solve the core problems that we’re seeing with the current generation of software.” In other words, Slack was an improvement on email, but that still leaves lots of room to improve upon Slack.—Nicolás Rivero

Five things we learned this week

Yelling at work isn’t always unprofessional. But it needs to be properly steered.

Women do not do the majority of talking at meetings. No matter what the Tokyo Olympics chief says.

Amazon’s new headquarters office will feature a helix. The history of architecture is abundant with examples of swirly structures.

Offices are great at creating ambient awareness. There are ways to replicate it in remote environments.

Clubhouse’s moment of free speech in China is over. Silicon Valley’s favorite new app has already been banned by Beijing.

Productivity for all

Getting more done takes more than a new app. Our new five-day email course will help you build healthy, sustainable productivity habits and develop an understanding of how to deal with your urgency bias and other challenges at the root of common obstacles to productivity. Sign up for free today.

30-second case study

Around 90 years ago, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt found his country in a similar state to most pandemic-hit economies today: beset by a severe economic shock and rising unemployment. One of his solutions was a radical one: to ask people to work less, so that more people could work.

When companies signed the Presidency Reemployment Agreement in 1933, they agreed to wage brackets and price caps. But they also agreed to shrink the working week of their employees. Artisans, factory workers, and mechanical workers, for instance, would work a maximum of 35 hours a week through the year, down from the usual 45-50; clerks, accountants, and sales staff would work no more than 40. Businesses that signed up would be able to advertise their involvement in the national recovery with a poster featuring a blue eagle and the words “We Do Our Part.” The government followed up by checking that firms were sticking to their promises. One study, from 2011, found that 1.34 million people found work through the agreement in just over four months.

The Covid-19 pandemic has sparked a new gravitation toward a shorter work week. Last year, IG Metall, Germany’s largest trade union, began bargaining for a four-day week, because the auto industry was facing the loss of at least 300,000 jobs. Last month, Spain set aside €50 million in incentive funding to companies willing to try a four-day week. And earlier this month, a British trade union voted for a shorter working week at the Airbus factory in Broughton, Wales. “We needed to have an alternative to furlough,” said Daz Reynolds, the union’s convenor at Airbus.

The takeaway: Roughly 6,000 people work at Airbus Broughton, more than the population of the eponymous town. About 400 jobs were in danger of being made redundant. Under the negotiated agreement, which runs for 18 months beginning this May, all employees will work either 5% or 10% fewer hours—time knocked off the present 35-hour work week that Airbus follows in Broughton. They’ll get paid 5% or 10% less as well, although Airbus has promised to pay a third of any lost wages back to the employees.

Economists and activists had already been pushing for a shorter work week in Europe even before the coronavirus hit, but the pandemic’s effects make the idea even more worthwhile, says Aidan Harper, a member of the 4 Day Week Campaign in the UK. “The idea is that you reduce the working week to distribute work more fairly across the economy, and so reduce unemployment,” he says. “People staying in work and having money in their pockets—that’s essential for an economic recovery. They spend locally, they employ more people, the money circulates. It’s essential that people spend during a downturn.”

Quartz field guide interlude

The essay at this top of this week’s email was adapted from our brand new field guide to the future of the digital workplace. Quartz members can read more about the apps that could change the nature of work, the companies that want to make the physical office obsolete, and the strategies that can help you avoid being controlled by your digital tools

Get access to all of Quartz’s field guides with a Quartz membership. Not yet a member? Sign up for a 7-day free trial!

Meanwhile, here’s an overview of some up-and-comers in the digital workplace tools business and what each one offers or promises to users:

📝 Notejoy Take notes and share with colleagues

👩🏫 Mural Work together on virtual whiteboards

🖌 Figma A collaborative design tool

🗣️ Otter Voice to text

🎥 Around Pushes video of colleagues’ faces to the side of the screen so you can fill most of your desktop with the thing you’re actually working on.

👯 Teamflow Connects colleagues via video and audio if their avatars get close enough in the virtual office

👾 Gather 8-bit renderings of offices where workers’ avatars “sit” at desks and “walk” to meeting rooms

💭 With An interface like a shared desktop where colleagues who are sprinkled around can talk on video and audio if their avatar bubbles get close together

😒 Sneek Takes a photo from your computer’s webcam every few minutes and pops it into a Brady Bunch grid with your co-workers’ faces, so everyone can see who’s available to chat and who’s concentrating and shouldn’t be bothered

💥 Reslash Co-workers build a shared screen with gifs, images, games, and links to create a tumultuous, overlapping, nonlinear mess

Has the pandemic been a reprieve for WeWork?

Since co-founder Adam Neumann’s exit, WeWork has laid low, quietly focusing on cleaning up a financial and public-relations mess while most of the world’s attention was directed elsewhere. CEO Sandeep Mathrani has reportedly cut the company’s annual burn rate by half; it now has at least $3 billion in cash on its balance sheet, plus a $1 billion commitment from majority owner SoftBank. And thanks to a flurry of IPOs via special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), this could even be the year WeWork finally goes public.

Not long before the pandemic, WeWork was trying to realize sweeping ambitions and a sky-high valuation; in 2021, it simply needs to prove that co-working can work.

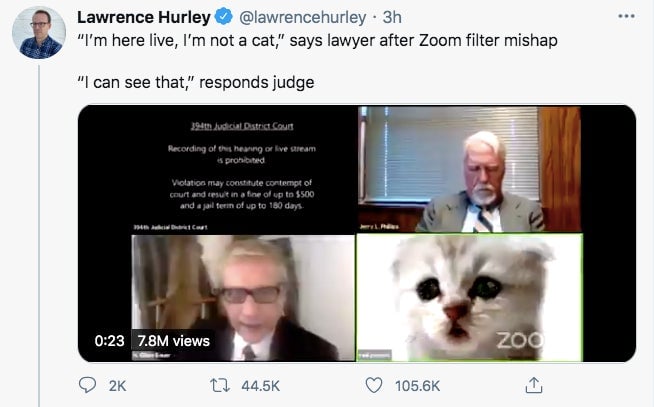

Will the Zoom fails ever cease?

Almost a year into the pandemic, CNBC viewers were treated to a Zoom countdown window during an interview with real estate magnate Sam Zell, and a lawyer in Texas accidentally showed up for court as a cat.

Words of wisdom

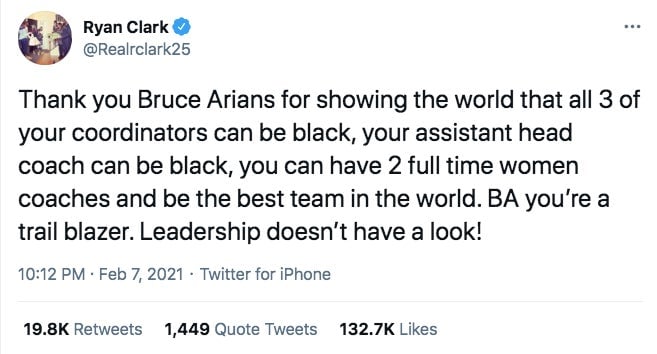

“Leadership doesn’t have a look.”—Ryan Clark, founder of defensive-backs training program DB Precision, commenting on the unusually diverse NFL coaching team for the Super Bowl LV-winning Tampa Bay Buccaneers

ICYMI

In our Quartz at Work (from home) workshop on Feb. 4, Jim Detert, a professor at the University of Virginia Darden Graduate School of Business and author of the forthcoming book Choosing Courage: The Everyday Guide to Being Brave at Work, offered a host of advice on how to marshal the pluck and goodwill that every skeptic needs to be successful in the workplace. Quartz members can access the video playback and a detailed recap here.

You got The Memo!

Our best wishes for a productive and creative day. Please send any workplace news, email replacements, and shortened work weeks to [email protected]. Get the most out of Quartz by downloading our app and becoming a member. This week’s edition of The Memo was produced by Heather Landy, Sarah Todd, Samanth Subramanian, and Michelle Cheng.