To modern workers everywhere,

Naomi Osaka’s withdrawal from the French Open has sparked a vital conversation about mental health in tennis and beyond.

On one side are those who say reasonable accommodations should have, and could have, been made for a star athlete who is being bravely upfront about both her recent history of depression and the anxiety she feels when forced to sit through press conferences that “bring doubt” into her mind. On the other side are those who see talking to the media as a vital aspect of professional sports and worry that freeing a player from her press obligations would uneven the proverbial playing field for other athletes in the tournament.

What if both sides are right?

Osaka took to social media on May 26 to declare that she wouldn’t be doing the requisite press conferences at Roland Garros this year, tournament fines be damned. And indeed she got fined, before announcing on May 31 that she would pull out of the tournament altogether so that “everyone can get back to focusing on the tennis going on in Paris.”

Osaka surely didn’t do any favors for herself by publicly announcing her intentions rather than taking her concerns straight to the people who could address them. (Should you need advice on how to have productive conversations with your boss about mental health, check out our guide to that here.)

On the other hand, the French Tennis Federation isn’t exactly known for its permissiveness—it’s unlikely a direct appeal would have accomplished much. But if it were unwilling to abandon its commitment to having players do media, might the federation have offered other concessions to Osaka? Could it, for example, have suggested new ways to structure the press conferences to make them less daunting? We’ll never know, at least not in time for this tournament.

L’affaire Osaka should be a fascinating case study for employers, who pre-pandemic had been slowly waking up to the mental-health needs of individual employees—and now face the prospect of managing through a global mental-health epidemic. Accommodations will need to be made. But what happens when middle ground can’t be found, when what an employee needs for the sake of mental health is at odds with the needs of the employer?

There will be no easy answers. In Osaka’s case, the result was a leave of absence from her sport’s center stage. Other cases won’t be so clear cut.

We all have learned a lot in the past year, up and down the org chart, about our must-dos and non-negotiables, and the areas in which we can afford to be more flexible or to revamp. The good news is, what might start out as an accommodation to one person or group often brings widespread benefits. Count on this prioritization exercise to not end anytime soon.—Heather Landy

Five things we learned this week

📈 Per capital GDP in China, Turkey, South Korea, Russia, and the US has fully recovered from Covid-19. Another 15 countries are expected to snap back to pre-pandemic levels by the end of the year, says the OECD.

🤯 IDEO is embroiled in a reckoning about race and sexism. Former employees are airing war stories about the design consultancy’s “white-dominant” company culture and calling out its allegedly “performative, equity-washing” gestures to address it.

😓 Overwork is the best birth control. To arrest declining birth rates, Beijing says married couples are now allowed to have three children. Overworked Chinese workers, however, say they’re too exhausted to even entertain it.

🦠 SARS-CoV-2 variants will be rebranded with names from the Greek alphabet. The World Health Organization adopted the naming system in an effort to minimize country-of-origin stigma. The newest of the four active strains is “Delta,” which was first detected in India.

💡 Figma built a solution for lackluster virtual brainstorms. With emoji-style prompts, a flowchart tool, and a voice chat function, its new interactive web-based whiteboard was designed to bring playfulness and parity to meetings.

30-second case study

With just six months of business under its belt and a 0.02% stake in ExxonMobil, activist hedge fund Engine No. 1 managed to get at least two of its nominees elected to the board of the oil and gas giant. The crux of the fund’s argument: Exxon has been consistently disappointing shareholders over the last 10 years and it needs fresh direction in a rapidly decarbonizing world.

Engine No. 1 founder Chris James, whose family foundation endows scholarships and supports conservation and environmental studies programs at a number of public universities, told Bloomberg that Engine No. 1 was born out of his attempt to start a new coal mine in the mid-2000s, near his hometown of Harrisburg, Illinois. But he saw the price of coal fall and the market for coal withering. It seemed to point to radical shifts in the use of energy, he said.

On Dec. 7, the hedge fund sent ExxonMobil a letter listing its four nominees for the board. “It is time,” the fund wrote in the letter, “for shareholders to weigh in.”

The takeaway: The past decade saw ExxonMobil’s total shareholder returns—dividends included—languish at -15%, compared to the 271% return the S&P 500 provided. That gave Engine No. 1 room to make an argument that was strategic rather than ideological. Its main message to investors: ExxonMobil has been consistently disappointing shareholders over the last 10 years, and it needs fresh direction in a rapidly decarbonizing world.

The ideals of the climate change movement had little to do with Engine No. 1’s methods, or its success. Instead, it campaigned on the idea that sticking to oil and gas, and not exploring clean energy alternatives, was an “existential risk” for ExxonMobil and its shareholders.

Other investors, including the Church of England the New York State Common Retirement Fund, had tried before to replace ExxonMobil board members, invoking the company’s long-term business prospects, global emissions levels, and the goals of the Paris agreement. Engine No. 1 broke through by focusing on the cost to shareholders, allowing a fund that manages $250 million in assets to set the stage for change at an oil juggernaut valued at $250 billion.

Upcoming workshop

As offices slowly reopen, many of us who adapted to working from home are wondering what comes next. Next Thursday, June 10, joins us for the final Quartz at Work (from home) workshop of the season, when we’ll explore the pitfalls and promises of hybrid workplaces, with expert guidance on how to mix things up productively. Keep your inbox tuned in for registration details.

ICYMI

YouTube, LinkedIn, Zoom. These are just some of the biggest tech platforms founded by Asian Americans. In an illuminating article on Quartz, Tom Mulaney, professor of Chinese history at Stanford University, introduces us to three pioneering yet largely unknown Asian scientists who laid the foundations for a globally connected world.

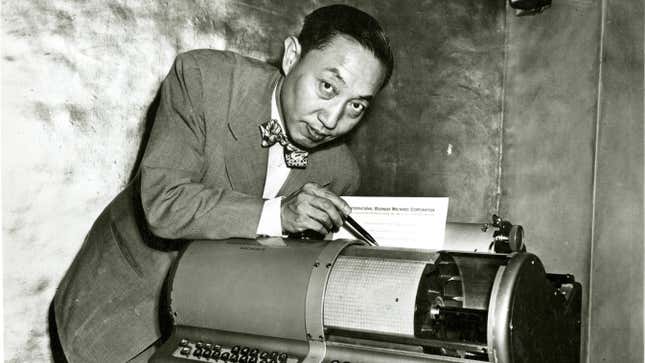

Chung-chin Kao, inventor of IBM’s first electric Chinese typewriter. Mulaney writes: “Kao’s electric Chinese typewriter was one of IBM’s first major Chinese-specific products, and at that point its largest. Although the machine itself was never brought to market—foiled by the civil war then raging in China, which made investors understandably hesitant—nevertheless the project augured a future in which IBM would invest ever more heavily in east Asian markets.”

Chan Yeh, the Taiwanese American engineer who translated Chinese characters for computers: “While working with IBM, he dedicated his spare time to exploring an entirely different venture—the electronic processing of Chinese characters. He felt convinced it should be possible to digitize Chinese characters, and thereby bring Chinese writing into the computer age. Yeh nicknamed his side-venture ‘Iron Eagle,’ on account of the Chinese characters that he first digitized: ying (eagle) and tie (iron).”

Leo Esaki, the Nobel-prize winning Japanese physicist made who made sense of electrons: “In 1957, Esaki and colleagues made the first demonstration of solid tunneling effects in physics, leading to a device that would come to bear his name: the Esaki tunnel diode, the first quantum electronic device. Discovery of the tunnel diode not only laid a foundation for further exploration in the electronic transport of solids, but it also inspired other advances in semiconductor science and electronics.”

To go deeper, read Mullaney’s full article here.

Quartz field guide interlude

A year after George Floyd’s killing, how can corporate leaders move from words to action to make a real difference?

This was the question a number of CEOs privately asked Robert F. Smith, the billionaire CEO of Vista Equity Partners. In response he proposed what he calls the “2% solution”—a principle by which large companies devote 2% of their earnings to any number of initiatives that help deliver racial equity. The number isn’t arbitrary, he writes; the average American family donates 2% of its income to charity each year.

“Large companies should do the same,” he says. “If enough companies did, they would deploy capital and expertise to unleash opportunity in Black communities, which would drive systemic and permanent change.”

Read Smith’s op-ed here, and click here for other answers to the questions raised in this week’s field guide: Can business step up for equality?

Not yet a Quartz member? Sign up now for a 7-day free trial.

Fashion emergency

The reopening this week of Quartz’s New York headquarters is both a milestone and, for some of us, a quandary: What should we wear to work now? The dilemma is particularly pressing for those who have sworn off “hard pants,” undergarments, form-fitting clothing, dressy shoes, or the circus of grooming appointments we considered necessary before the pandemic.

In her timely deep dive on the evolutions of the “professional look,” Quartz senior reporter Sarah Todd examines the questions that many of us have long held about fitting in, sartorially speaking, at work—and ultimately argues that this is the perfect time for employers to question how they picture professionalism.

Fun fact!

There’s a term for finding moments of delight in your work wardrobe. It’s called “dopamine dressing“.

Words of wisdom

“The wider world perceives fashion as frivolity [and] that should be done away with. The point is that fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life. —Bill Cunningham, fashion photographer

The beloved chronicler of street style who passed away in 2016 believed that getting dressed is a civilizing act.

🎩 Office tunes: This Memo was produced while grooving to a loop of Jamiroquai’s Virtual Insanity. The funky earworm was the mood-setting ditty at Quartz’s last all-staff meeting.

You got the Memo!

Our best wishes for a breakthrough week. Please send any workplace news, re-entry fashion highlights, or brainstorming gems to [email protected]. Get the most out of Quartz by downloading our app and becoming a member. This week’s edition of The Memo was produced by Anne Quito, Samanth Subramanian, Oliver Staley, and Heather Landy.