This week’s lead story is by Sarah Todd, a senior reporter at Quartz. Inspired by the life and work of the artist Alberto Giacometti, Sarah explores how to know when a project is finished. And how to let it go.

Alberto Giacometti was a prolific artist—a fact that’s also a small miracle, given his notoriously laborious creative process. Best known for the stark, elongated figures embraced by critics as emblems of a ravaged but persevering humanity in the aftermath of World War II, the Swiss sculptor and painter could toil so long over his works that he risked whittling them away into nothing. “Often they became so tiny that with one touch of my knife they disappeared into dust,” Giacometti wrote in a 1947 letter to Pierre Matisse.

The tortured nature of Giacometti’s quest for excellence, as captured in a new traveling exhibit of his post-war work, may prompt visitors to feel an unexpected sense of kinship with one of the most renowned artists of the 20th century. There’s a thin line between holding one’s work to high standards and slipping into self-destruction—an application never submitted, a project never launched, a brittle statue crumbling at the nick of the knife. If we want to share the things we create with the outside world, there comes a point at which we must be done with our work, at least for the time being. So how to let go?

A documentary included in the exhibit, filmed shortly before he died in 1966, shows a charmingly self-aware Giacometti describing the futility of striving to create work that lived up to the vision he had in your head.

“There can be no possible end, because the closer you get to what you see, the more you see it,” Giacometti explains as his fingers pull at the clay bust in front of him. “Then the distance between what I want to do and what I am doing remains basically somewhat permanent […] I am convinced that in a thousand years, I would tell you, Everything is wrong, but I am getting a little closer.”

Such a process would be perfectly reasonable if Giacometti had been blessed with immortality. Things being as they are, the saving grace that seems to have allowed Giacometti to relinquish his work was his penchant for repetition.

This quality is sometimes levied as a criticism against the artist. His frenemy Pablo Picasso suggested that going back to the same subjects and ideas over and over again made for a rather monotonous oeuvre. But in returning to certain motifs—men walking, women standing—Giacometti was able not only to explore “variation within sameness,” as one critic put it, but to accept that an individual piece had not lived up to his expectations. Perhaps the next time, it would: the possibility propelled him forward, even knowing that failure was inevitable.

“Trying is everything,” Giacometti wrote in one poem, “how marvelous!”

Ultimately, the secret to knowing when a project is finished may have less to do with the project itself than the anticipation of the next effort ahead.—Sarah Todd

Read the rest of this story on Quartz.

Five things we’re reading this week

🔥 Even Beyoncé is burned out. The pop star’s latest single is a manifesto for the great resignation.

📉 Bitcoin’s crash is good news for the environment. Energy consumption is falling for the first time, as major bitcoin mining operations are shutting down.

💎 Should Russian diamonds be categorized as “conflict diamonds”? The world’s largest producer of diamonds is doing all it can to avoid the damning label.

♀️ There are still not enough women in Indian’s military. The Agnipath protests in India—and the young men leading them—are proof of the abysmal level of female participation.

👜 Chanel is launching exclusive boutiques for top clients. These invitation-only stores are set to open in Asia first.

Charted

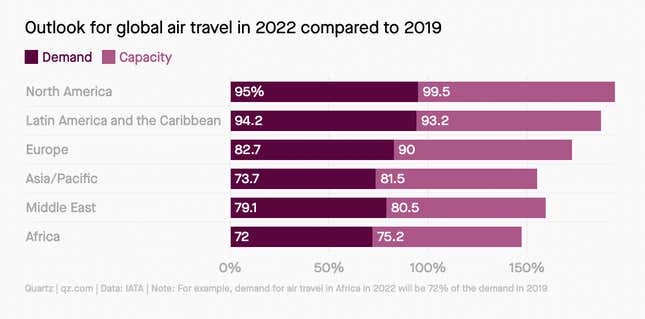

Global air travel’s great recovery is not happening at the same pace across the world, reports Alexander Onukwue, Quartz’s West Africa correspondent. While demand in North America this year will almost be equal to 2019, demand in Africa will be significantly lower. The reason? Lower covid-19 vaccination rates, says the International Air Transport Association.

30-second case study

Apple is an on-again, off-again most valuable company in the world. It was the first American corporation to reach a valuation of $3 trillion earlier this year. But even at more earthly valuations (like its current $2.2 trillion), it remains an investor’s darling, showering shareholders with stock buybacks and dividends.

Apple employees at many of its retail stores, however, are less satisfied with the way the company has rewarded them for their contributions to the brand’s success. The tech firm made $366 billion in revenue in 2021, 36% of which was earned through Apple Store sales. And yet hourly workers in the US say that it has been difficult to make a living, especially as inflation rises.

To be sure, Apple is seen as a good employer. The minimum starting wage for store workers was recently boosted from $20 to $22 per hour, and employees are eligible for several benefits, which is still unusual for most retail employees.

However, that wage increase didn’t come out of the blue. In February, the Washington Post reported that union organizing was taking hold at 14 Apple store locations across the US, including at a store near Baltimore, Maryland, and at New York’s Grand Central Terminal store. (The Maryland organizers, who call their union AppleCORE, for Apple Coalition of Organized Retail Employees, are aligned with the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers trade union. Employees at New York’s Grand Central store are backed by the Communications Workers of America.) The workers behind these campaigns say Apple found the budget to increase wages only to fend off unionization efforts.

If so, it didn’t work. On Saturday, June 18, store employees in Towson, Maryland voted to become Apple’s first union in the US.

“I ask Apple CEO Tim Cook to respect the election results and fast-track a first contract for the dedicated IAM CORE Apple employees in Towson,” IAM international president Robert Martinez Jr. said in a statement, adding, “This victory shows the growing demand for unions at Apple stores and different industries across our nation.”

The takeaway: Fueled by labor shortages, the pace of change in the US labor movement is astonishing. Companies that aren’t prepared to embrace empowered employees may be putting their reputations at risk.

Martinez could have named several other companies which find themselves in Apple’s position. Some Amazon warehouse employees in New York successfully unionized in April. Starbucks workers have already voted to unionize at more than 150 stores. Employees at a Trader Joe’s location in Hadley, Massachusetts filed for a union election this month, with an eye to becoming the first unionized store in that nationwide chain.

Apple also isn’t the only “progressive” firm on this list. But companies that boast about being ethical employers shouldn’t be surprised to find their staffers holding secret meetings about unionizing: the companies themselves have raised workers’ expectations.

Importantly, the issues at stake for many members of the new labor movement go beyond pay and benefits. Employees are also looking for more of a voice in corporate decisions. Maryland’s Apple store employees made that point in an open letter to Apple chief Tim Cook last month, adding that their collective action was sparked by a love of their jobs, “not to go against or create conflict with our management.” (Unfortunately, Apple already stands accused of using union-busting tactics.)

These employees and others are essentially demanding that employers live up to the values of stakeholder capitalism. At this point, the leaders who are quickest to do so are likely to gain a competitive edge by attracting and retaining workers—and avoiding protracted battles.

There are more than 270 Apple Stores in the US, and the Maryland union says it’s getting calls from from workers everywhere who want to learn about the unionizing process.

You got The Memo!

Today’s Memo was written by Sarah Todd, Lila MacLellan, and Anne Quito. It was edited by Francesca Donner. The Quartz at Work team can be reached at work@qz.com.

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up for future installments here. Get the most out of Quartz by downloading our app and becoming a member.