Hi Quartz members,

The nickname coined itself: the Blade Runner. What else to call Oscar Pistorius, the South African sprinter who burst onto the scene in the early 2000s, wearing prosthetic feet that bent and curved like blades? Those blades, still novel in competitive sport when Pistorius first started racing, are the standard today. At the Tokyo Paralympics in 2021, all runners with prostheses wore blades.

The Pistorius blade (the Cheetah) is only one specialized kind of prosthesis, though—the billion-dollar market mainly serves people who just want to walk to the grocery store or pour a glass of milk. Össur, a little-known Icelandic company, is one of the two biggest prosthetics manufacturers today, making not just elite athletic limbs but also daily-use hands, feet, and legs for amputees.

In just a few decades, prostheses made by Össur and other companies have grown incredibly sophisticated. Running blades, for instance, are made of thousands of strong, fine layers of carbon fiber sandwiched together. “The materials are always evolving, driven by aerospace and automotive applications,” says Christophe Lecomte, Össur’s director of biomechanical solutions. Nike designs soles especially for the bottoms of these blades. Increasingly, microprocessors and motors live in the core of these devices, making them more powerful and sensitive still.

The debate that Pistorius sparked—over whether prosthetic limbs have gotten so good that they give their users an advantage—is intriguing, but also a sidelight. The real story of the progress of these devices lies in how Össur and other firms are trying to fabricate limbs that can be controlled by the human brian, just like real limbs. For Össur, the ultimate triumph would be a prosthetic that moves and works precisely like the limb it is replacing—to the point that its user forgets it’s even there.

A 🎙️ interlude

Have we piqued your interest in prosthetics? The latest episode of the Quartz Obsession podcast explains what could go wrong when technology starts to focus on augmenting able bodies for superhuman functions. 🎧 Listen here or 👀 read the transcript.

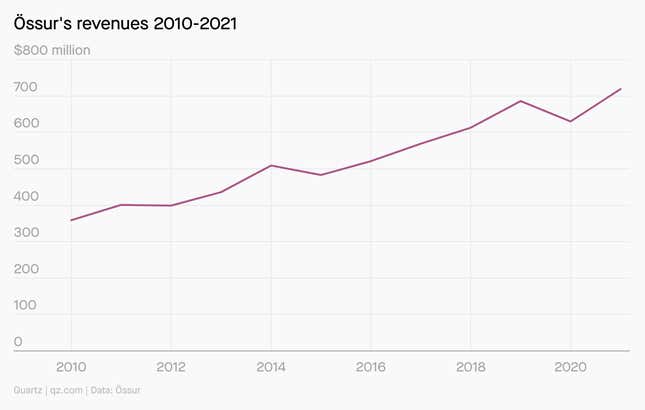

By the digits

$719 million: Össur’s 2021 sales, up from $630 million in 2020

$50,000: The upper end of the cost range for sophisticated prosthetic limbs

4,000: Össur employees, across 30 locations.

2 million: Cycles of testing undergone by a single Össur running blade

28: Medals won by athletes with Össur prosthetics at the Tokyo Paralympic Games

25 hours: Battery life of the latest model of Össur’s motor-powered, microprocessor-enabled knee

Origin story

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that Össur Kristinsson went into prosthetics: He was born in Iceland with a malformed leg, which required an amputation later in life. After studying prosthetic science in Sweden, Kristinsson opened a clinic in Reykjavik in 1971 to help fit amputees into their artificial limbs. But he soon noticed a persistent problem: An amputated limb would usually be forced straight into the prosthetic’s socket, resulting in chafing, pain, and hampered mobility. “People would put cotton or wool socks to protect the limb where it goes into the hard socket,” says Össur vice president Edda Geirsdóttir.

In 1986, Kristinsson invented a silicon liner—an interface in the socket that protected the human limb. The liner did so well that, through the 1990s, Össur was pretty much a one-product company. Only in 1999, after going public, did it start to look around for acquisitions. The following year, it bought Flex-Foot, which made the now-famous blade-like foot, for $72 million. The purchase set Össur firmly on a path into the heart of the prosthetic limb business.

A big player in prosthetics

Prosthetic devices like running blades and power knees form 63% of Össur’s total sales. In the global market for such prosthetics, valued at around $1.4 billion, Össur is the second largest company, with a share of 24% of the market.

The everything material

In 1976, a young undergraduate named Van Philips got into a terrible water-skiing accident, losing his leg below his left knee. The prosthetic limbs available at the time were blocky replicas of real legs, so Philips set about designing a new one: the Flex-Foot, inspired by the springy hind leg of a cheetah. It was the first model of the Össur running blades we see today.

When Philips was searching for the right material for his invention—something strong, light, cheap, and heat-resistant—he lit upon carbon fiber. The first filaments of carbon were created more than a century ago, for use in light bulbs, but its properties were refined only in the 1960s. By itself, a single strand of carbon isn’t very strong, but when thousands of fibers (each thinner than a human hair) are woven and compressed together, the material gets up to 18 times stronger than steel.

Among the first companies to use this space-age material was Rolls-Royce, which made jet engines out of carbon composites in the late 1960s. Since then, carbon fiber has made its way into practically everything except the food we eat. It’s in airplane and car components, motorcycle racing gloves, wind turbine blades, power lines, microchips, spectacle frames, clothing, and skis.

It’s a marvel—except that it comes with a cost. Carbon fiber, despite its organic-sounding name, isn’t biodegradable, so landfills are brimming with the stuff. Recycling it is difficult, because that helpful imperviousness to heat makes it difficult to melt down and reuse. The development of carbon fiber was a true revolution, but as with so many other wondrous technologies, it now requires a second revolution, one that determines how we can use it without letting it ruin the planet.

Watch this!

At the Tokyo Paralympics, the Netherlands’ Fleur Jong, a double amputee on Össur blades, won the long jump. She broke her own world record in the process, which she’d set earlier in the summer, at the World Para Athletics European Championships in Poland.

Keep learning

- One German company has run tech support for prosthetics at the Paralympics since 1988 (Quartz)

- The prosthetic foot so advanced, it may even send amputee soldiers back into battle (BBC)

- Brain controlled prosthetics are finally real (WIRED)

- An amputee’s company will help Paralympians run and jump in Tokyo (Quartz)

- For jumper, renewed debate over athletic versus prosthetic (New York Times)

- Neuroscience research and AI are driving a revolution in bionic limbs (WIRED)

- 🎧 Prosthetics: Upgrade available (Quartz)

Have an enhanced end to your week,

—Samanth Subramanian, senior reporter

PS: Last week’s email about Nextdoor incorrectly stated the total number of global Nextdoor users (69 million, not 36 million), and misstated the year the Kindness Reminder was introduced (2019, not 2020). We regret these errors!

One 🤡 thing

When Össur was negotiating to buy Flex-Foot, the American company’s founder, Van Philips, grew curious about the low rate of lifestyle diseases in Iceland. Philips, a vegetarian and a devotee of healthy living, posed the question to two Össur executives during a lunch break. Was it true, Philips asked, that Icelanders didn’t eat junk food? The executives, both overweight men, looked at each other. Then one shot back: “How do you think we achieved this shape? Eating bananas?”