Hi Quartz members,

A hundred years from now, people won’t remember much about the covid-19 pandemic. Memories of masked gatherings and lines for testing will slip out of the popular consciousness. But it’s likely something else will have more staying power: mRNA (messenger RNA) technology.

The speed at which companies developed vaccines against covid-19 gave the world a taste of the potential for technologies built around mRNA, a genetic molecule that exists in all of the body’s cells and gives them instructions to create the proteins necessary for it to function. Although mRNA naturally occurs in most organisms, it can be recreated in a laboratory, too; when used in a vaccine, it trains the immune system to respond to an infection as if it had been exposed to a pathogen.

But this isn’t something that can only be applied in the case of pathogens like viruses. The truly revolutionary promise of mRNA technology rests in the fact that it could provide a highly tailored—and fast—response to a person’s cancer, or dial down the exaggerated immune responses that cause autoimmune conditions.

It’s our first real hope for an everything vaccine, so to speak.

EXPLAIN IT LIKE I’M 5!

For more than two centuries, all vaccines were essentially made the same way: They were simply an inactive virus or bacteria in a solution. The immune system of the patient receiving the vaccine would have a small reaction, but most importantly would remember the pathogen so that it would know to attack it should it be faced with an active version of it.

But mRNA vaccines work differently. They instruct the organism to create a protein (or even a fraction of protein) that triggers an immune response without the need to expose the body to the pathogen at all. This significantly speeds up the development timeline.

WHAT COVID TAUGHT US

Though mRNA vaccines had been in the works for years, scientists had no real-world evidence that mRNA technology actually worked in humans until two years ago. Now they know for sure. This caused enormous enthusiasm within the scientific and medical community, leading to large investments in ongoing and new trials. Some anticipate that mRNA is the future of vaccines and, potentially, pharmacology more broadly.

In the months since the large-scale deployment of mRNA vaccines, however, researchers learned a few more things, too. Indeed, mRNA vaccines can be made at great speed and work, but they also seem to cause more severe reactions after the injection. In the future they may be best used when there is need for new vaccines on a quick turnaround but then switch to other types of vaccines for boosters. Researchers will still need to compare the efficacy of mRNA vaccines with traditional ones in situations where speed isn’t as important.

THE EVERYTHING VACCINE

Research into mRNA vaccines to treat infectious diseases has been going on for decades, but the success of covid-19 vaccines has sped it up. Researchers are looking to mRNA vaccines to treat conditions such as HIV, malaria, Zika, the flu, and Lyme disease. New mRNA vaccines against cytomegalovirus (a common virus that can be dangerous during pregnancy) and the respiratory syncytial virus (a severe respiratory virus affecting mainly children) are in late-stage clinical trials and could become available in the next couple of years, offering more opportunities to evaluate the performance of mRNA vaccines.

But research is also well underway to apply mRNA technology far beyond external pathogens, to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis and for highly tailored cancer vaccines targeted to individual patients. Moderna is already exploring at least 14 products that use mRNA technology to treat conditions that aren’t caused by external pathogens, on top of almost two dozen new vaccines against pathogens. BioNTech, too, is working on five mRNA products to tackle a variety of cancers.

It will take time, and a lot of money, for these new treatments to become available on the market. But if and when they do, they will represent an epochal shift in disease treatment.

HOW SOON IS SOON?

The astonishing speed at which the covid-19 vaccines were developed doesn’t guarantee that future mRNA technologies will come nearly as fast. Some of the unique ingredients that made it possible for vaccines to go from zero to the arms of millions in less than a year—notably, huge government investments, global scientific cooperation, emergency authorizations from regulatory bodies—are unlikely to converge outside the pandemic.

This means that it might very well take years before we see the next mRNA products, though optimistic estimates predict a non-vaccine application within five years, and dozens more in the next decade.

In the meantime, traditional vaccines are still being developed, tested, and introduced to fight the many pathogens we have yet to defeat—from the flu, to malaria, to ebola.

SHOW ME THE MONEY

Because they developed successful covid-19 vaccines, Moderna and BioNTech (Pfizer’s vaccine partner) profited enormously from the pandemic. Moderna made more than $11 billion in the first nine months of 2021; BioNTech, whose vaccine became the most sold drug in a single year, raked in more than $13 billion in the same period. These companies will keep making money off these vaccines as long as covid-19 is around, though their revenue will likely diminish as the virus becomes less of a threat.

This puts the two companies in a position to lead their field. While there are hundreds of biotechnology companies working on RNA research, including mRNA technology, only Moderna and BioNTech can reinvest their massive windfall in new research and to acquire smaller competitors.

That means it will be very difficult for smaller upstarts to challenge them. They can come up with effective products, but even breakthrough successes will hardly reach the same scale, unless there’s the mass mobilization of resources to combat an epochal event like the pandemic.

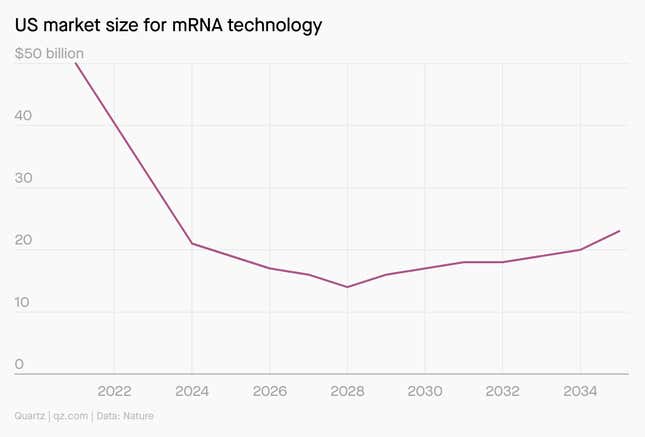

Still, there’s so much being built around mRNA that there will be space for small players as well as leaders, at least in the medium term. An analysis from Nature predicts that, in the next couple of years, covid-19 vaccines will make up the entirety of the market around mRNA technologies. But as the need for covid-19 vaccines diminishes, the market will shrink until new products become available. After that, the sky’s the limit.

Keep learning

Kati Kariko helped shield the world from Coronavirus (New York Times)

The founder of Moderna doesn’t think vaccines are all that impressive (Quartz)

Could one shot kill the flu? (The New Yorker)

Has Covid-19 permanently altered the development timetable for other vaccines? (Quartz)

The age of genetic medicine (Quartz)

Evolution of the market for mRNA technology (Nature)

🔮 PREDICTION

Vaccines and treatments for complex diseases are cool, but in the future mRNA technology could be used to treat conditions that the immune system can’t address. For instance, if a missing protein is causing a heart issue, an mRNA injection could instruct a person’s body to produce it.

This use of mRNA would be very different from what we have known so far, and is much further from becoming available, but could have enormous impact.

Sound off

Do you think mRNA technology will live up to the hype?

Yes, I think it’ll treat lots of diseases

No, I think it’ll be more limited

In last week’s poll about the economy in 2022, 50% of respondents said they expect the tech bubble to burst this year.

Have a great week,

—Annalisa Merelli, senior reporter (and vaccine enthusiast)

ONE 🇨🇳 THING

There is currently no mRNA covid-19 vaccine approved in China. Sinovac, China’s homegrown vaccine, is a traditional vaccine in that it uses an inactivated virus.

Although Pfizer’s vaccine is licensed to the Chinese company Fosun Pharma, it has yet to receive approval from Chinese authorities.It might not until the first locally developed mRNA vaccine—ARCoVAx, which is currently running trials in China as well as Mexico and Indonesia—is ready to hit the market, as the country is keen to establish its vaccines as preferred against Western-developed ones.