Hi Quartz members,

Vladimir Putin caught much of the world off guard when he sent tanks and troops into Ukraine, but he was likely just as shocked when the West blew a huge hole in his prized bulwark: Russia’s billions of dollars in foreign exchange reserves stashed around the world.

That’s only one in a battery of measures that also target Russia’s biggest banks, politicians, oligarchs, and its access to key products and debt markets. In a remarkable show of cooperation, Putin’s opponents even threw in the largely symbolic step of booting Russia out of SWIFT, the banking communication system.

This is economic warfare at an unprecedented level. It’s true that, over the past decade, the global use of sanctions has exploded to the point of making them routine. But most of the time, they are much narrower—aimed at certain individuals, institutions, or industries—or applied over a much longer timeline, or against a much smaller economy, as in the case of Iran. The speed, scale, and sweeping nature of the Russian sanctions make them the equivalent of an economic blitzkrieg.

Revolutionary as they may be, they’re the logical progression in the evolution of what has been called “the economic weapon”. With each new round of sanctions, both sides adjust—new ways of sanctioning prompt new ways of avoiding sanctions. To protect itself against WWI-style blockades, Germany sought to become self-sufficient, a logic that fed Hitler’s 1939 invasion of Poland. Similarly, Putin built his foreign exchange reserves to bypass 2014-style sanctions after Russia’s invasion of Crimea.

The latest offensive will no doubt lead to further adaptation. In the meantime, will it force Putin to change course? In the past, we have seen sanctioned leaders carry on regardless of economic duress. Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro is one recent example.

But with Russia, the sanctioners’ gambit is more dangerous. Given Russia’s bigger role in the world economy, the potential of spillover is much greater than with Venezuela (or Iran or Syria). And none of those countries have nuclear weapons. In response to the new sanctions, Putin put Russia’s nuclear forces on high alert. It’s a reminder that economic and physical warfare cannot be easily disentangled.

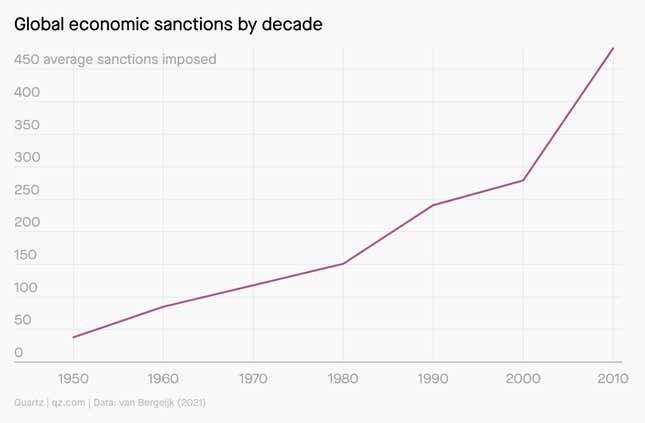

Charting the rise of sanctions

The average number of sanctions per decade has increased since the end of the Cold War in 1990. Economist Peter A.G. van Bergeijk suspects this isn’t a coincidence—they’re more palatable than an armed conflict, with less collateral damage than some other interventions. They also coincide with shifts in the openness of the world economy—the economy became more global after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Economic interdependence gave sanctions more teeth, so their use spiked.

The backstory

Normally, given the protracted nature of diplomacy and the legislative process, sanctions take months, even years, to devise. The Western sanctions against Russia came together within a week. Never before has such a large country been so swiftly sanctioned at such scale.

In part, this is because sanctions experts have, out of long practice, built a reliable playbook, and because they’ve been studying Russia’s vulnerabilities since 2014. In 2018, the economist Daleep Singh—now a key Biden adviser—testified about the US’s discoveries of what works against Russia: restricting access to foreign capital, targeting state-owned companies, cutting off technology supplies.

But the Russia sanctions also emerged so quickly because the conflict triggered a wave of public pressure, helped in large measure by the public profile of Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s president, and by the images of Ukrainians arming themselves. There are harsh geopolitical truths here. The public chose to care about Ukraine, an outpost of Europe, in a way it didn’t for Myanmar or Sudan. And the US is more willing to confront Putin’s regime than it is, for example, Saudi Arabia, with whom it maintains a working relationship.

No set of sanctions is guaranteed success; in fact, most sanctions fail. But since they are among a small set of tools that can be used to try to influence rogue states, they will continue to be a go-to. Future sanctions architects will learn a lot from the past week: the benefits of getting public opinion on side with a generous release of intel, for instance, or of long-term studies of economies. But they’ll also have to plan for public fatigue with sanctions, and for domestic side effects—such as rising gas prices—that turn people against sanctions altogether.

What this means for China

China loathes what it calls US “financial hegemony” and its ability to sanction foreign countries. It has refused to join the West in sanctioning Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, saying such “unilateral sanctions” are illegal and counterproductive.

In the meantime, Chinese officials, academics, and experts are watching the widening global economic war against Russia and thinking about how to better sanction-proof China.

One investor argues that China should more deeply integrate into the global economy (link in Chinese). “Only with a deeper and broader integration with other countries’ economies and investments will the so-called economic sanctions have a ‘half-hearted’ effect,” he writes.

But in seeking integration, China shouldn’t risk (link in Chinese) “excessive financial dependence on the US,” noted a professor of international relations at Fudan University.

And with China’s homegrown cross-border payment system CIPS still reliant on SWIFT, an analyst at Citic Securities says China must “vigorously promote the internationalization of the renminbi,” focusing on CIPS and the digital yuan.

🔮 Predictions

Right now, everything about the war in Ukraine is uncertain and changing quickly. We rounded up predictions from experts and from prediction markets to present a range of opinions on what could happen next. (The quotes from experts were made at two separate events on Thursday, March 3.)

🇺🇦 Ukraine

Despite the Russian military’s stumbles and diplomatic talks between Russia and Ukraine, online prediction platforms give between a 40% and a 60% chance that Kyiv will fall to Russia in the next two months.

🇷🇺 Russia

The ruble will keep falling, said Anders Åslund, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Crypto won’t save the Kremlin. “If I were trying to get money out of Russia right now, I would launder it, I wouldn’t use bitcoin,” said Atlantic Council senior fellow Julia Friedlander.

🇪🇺 Europe

In 2022, economic growth in Europe will be about half a percentage point lower than otherwise due to the conflict and sanctions, predicted Ludovic Subran, chief economist of insurer Allianz.

Europe might decide to invest in energy independence, added Subran. (Here’s what that might look like.)

🇺🇸 US

“The macroeconomic implications [of the conflict] for the US are limited,” said Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

The Federal Reserve will still raise interest rates as planned, Posen added. (Forecasters and prediction markets agree.)

Keep learning

The sanctions reflect the global economy’s convoluted architecture—and so will their effects. How do the pieces fit together? We have questions (and some answers).

- How will sanctions reverberate around the world? (Derek Thompson)

- What happens to China’s relationship with Russia? (Voice of America)

- Why was energy not included in the sanctions? (TIME)

- How could Russia suddenly lose access to billions of dollars in reserves? (Financial Times)

- Is there an exit ramp for the sanctions? (Washington Post)

Sound off

What do you think the main effect of sanctions will be?

They make an end to the war more likely

They will deter future invasions

They will hurt everyday people without accomplishing much

In last week’s poll about the future of fast fashion, 47% of respondents said they’d rather buy fewer clothes that are more expensive. Our wardrobes may be all basics, but they’ll be a lot more sustainable.

Have a great week,

—Ana Campoy, deputy economics and finance editor (dusted off her international relations major this week)

—Samanth Subramanian, fixing capitalism reporter (whose international relations major is too far buried under dust to excavate)

—Mary Hui, reporter (pondering how China thinks about security)

—Walter Frick, executive editor, membership (old enough to remember the End of History)

—Alex Ossola, membership editor (keeping an eye on the ruble)

One ⚔️ thing

Economic sanctions are often thought of as an in-between point between words and bullets. Originally, though, they were conceived as weapons just as capable of killing as conventional warfare. “(W)e tried, just as the Germans tried, to make our enemies unwilling that their children should be born; we tried to bring about such a state of destitution that those children, if born at all, should be born dead,” said William Arnold-Forster, a British blockade manager during WWI. Those blockades killed hundreds of thousands of people through hunger, as Nicholas Mulder chronicles in his new history of economic penalties. Countries have since become more mindful of targeting sanctions to limit their harm, but that doesn’t mean they’re not violent—one of the reasons why Mulder argues for a rethink of “the economic weapon,” which serves as the title of his book.