Hi Quartz members,

The wildcards struck early this year. Our January guide to the economy in 2022 included four hard-to-forecast but potentially important disruptors, one of them a Russian invasion of Ukraine.

War is especially difficult to predict—at the start of the year, most online forecasting platforms put the chance of an invasion at less than half—which is why we’ve published a “wildcards” list for each of the past three years. We look for events that might not be likely but that are plausible and would have an outsized effect on the economy if they occurred. It’s a bit like the “pre-mortem” exercise, where you imagine that a choice you’re about to make turns out poorly and then hunt for reasons why that could be. Each year we imagine what could go wrong for the global economy and list the possible culprits. In 2020, our list included a then-novel coronavirus.

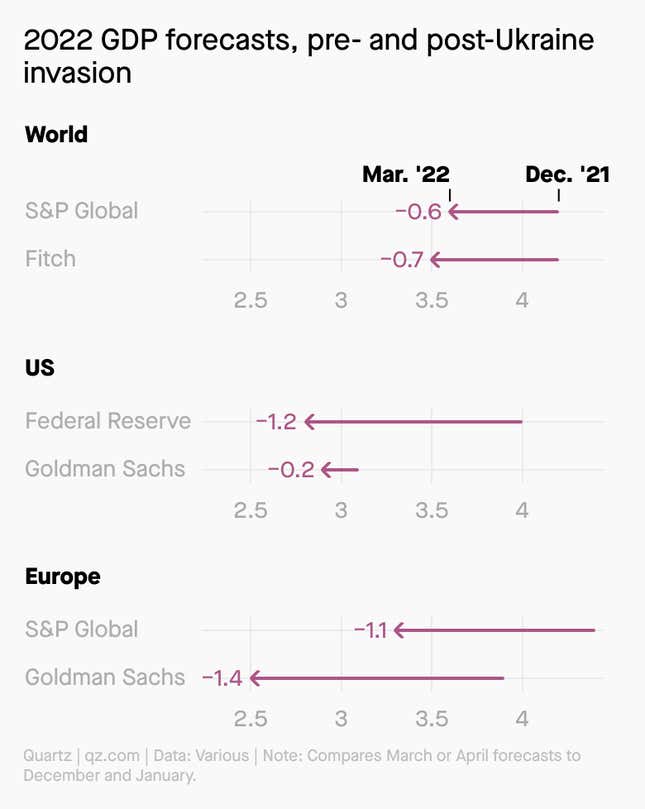

With all that’s happened since January, we thought we’d look back at the topics from this year’s guide and provide an update. We cover inflation, supply chains, and covid—and we’ve added energy to the mix. Unfortunately, the news is mostly bad: As you can see in the chart below, the prospects for the global economy are looking quite a bit worse than they did just three months ago.

📉 LOWER YOUR EXPECTATIONS

Forecasters on Wall Street and at central banks have lowered their estimates of economic growth for nearly all regions of the world, with the steepest adjustment for Russia—which S&P Global estimates will shrink by nearly 9% this year. In the US, the Federal Reserve cut its annual growth forecast from 4% to 2.8%, and Goldman Sachs says there’s a 20-35% chance that the US enters recession this year.

🛢️ ENERGY CRISIS

In February, the price of oil topped $100 per barrel for the first time since 2014, and natural gas prices surged as well. In May, the US will begin releasing oil from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve and is sending more natural gas to Europe, but in the short term there are no good alternatives that could completely replace Russian oil and gas. Oil prices (and therefore gasoline prices) may climb even higher, and that’s one of the biggest causes of those darkened economic forecasts in the chart above.

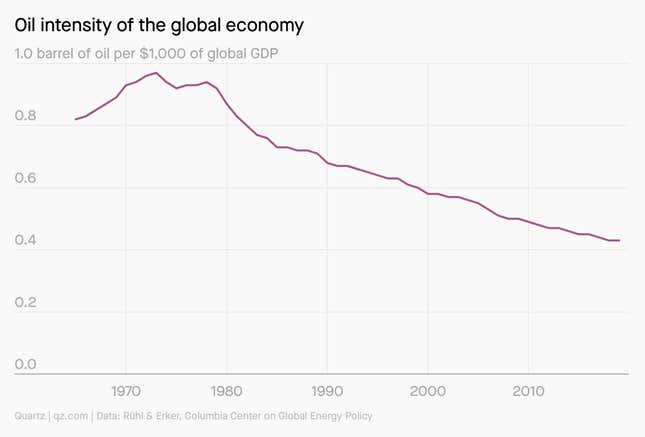

The good news is that the global economy has never been so insulated from high oil prices. It relies less on oil for electricity than it once did and is more energy efficient overall, which makes temporary price spikes more tolerable.

💸 INFLATION RISING HIGHER

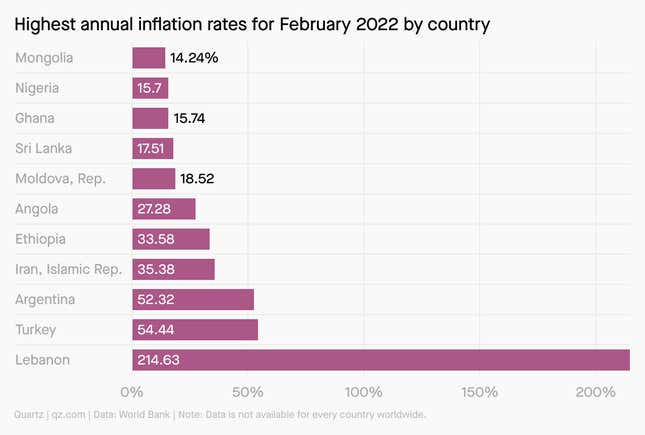

The dynamics behind 2021’s high inflation numbers have persisted in the first quarter of 2022. After a half a century of falling inflation rates, the global annual inflation rate has now climbed above 6%.

Central banks around the world are making borrowing more expensive to slow down the increase in prices. But interest rate hikes are a blunt tool, and will not build more semiconductors or houses. The World Bank also estimates that a dozen poor countries are headed for default in the next year, as rising interest rates make their debt more expensive.

The global economy is facing rising food and oil prices in the face of Russia’s brutal and unprovoked invasion of Ukraine—adding more inflationary pressure.

The persistent rise in prices is another reminder of the market’s inability to foresee long-term risks and build resilience for them. Inflation is hard enough to manage when everything else is going well. But our current system prioritizes short-term earnings over long-term resilience, writes Joseph Stiglitz, chief economist at the Roosevelt Institute. That means more crises, he argues, and each one potentially making inflation that much harder to tame.

😷 Inching towards endemicity

Much of the world is starting to shrug off the pandemic, as hospitalizations fall due to a combination of vaccination and previous infection. Except China, which remains committed to its zero-covid policy even as it fails to contain the biggest spike in cases yet. The policy will likely stay in place at least until the end of 2022, when Xi Jinping is expected to announce his third term. Until then, the government’s priority will be to avoid any political disruptions like a surge in severe cases or overrun hospitals. That commitment comes with consequences for the rest of the world as the Chinese economy slows down. One tally put the lost productivity from China’s patchwork of covid lockdowns at nearly $50 billion a month, and they’re one reason ocean shipment volumes are down.

The return to normal, both economically and otherwise, could be further delayed if a new, deadlier variant of the virus pops up.

📣 SOUND OFF

Which is the biggest threat to economic growth this year?

- An energy crisis as oil and gas prices rise

- Continued inflation and the possibility of a central bank-induced recession

- The next wave of covid

- Something else

Last week, 35% of you said the Digital Markets Act won’t dent the tech giants. Their investors hope you’re right.

Have a great week,

—Ana Campoy, Nate DiCamillo, Walter Frick, Tripti Lahiri, Tim McDonnell, Samanth Subramanian

One 🏘️ thing

A full quarter into the new year, the Chinese property giant Evergrande is generating fewer global headlines but is still hobbled and limping. In March, it missed its deadline to publish its annual results, and after its $22.7 billion default last December, it is being kept afloat by the Chinese government. By July, Evergrande has said, it will divulge how it will restructure its debts of $300 billion. In the interim, Evergrande is still causing ripples throughout China. Local banks seized $2 billion of its cash without the company’s knowledge, stoking anxieties among foreign creditors. But the full-scale collapse of banks and companies that many feared hasn’t transpired—a hopeful sign, for markets and investors everywhere, that China is turning this into a controlled implosion.