Hi Quartz members,

If your interests lie at all in the health of the US economy—you’re a Quartz member; of course they do!—you will have watched closely a couple of days ago as the Bureau of Economic Analysis released second-quarter GDP data. And although you may not have said the word out loud, it must have quivered in the air around you, with a question mark appended to it: “Recession?”

The numbers weren’t heartening. The economy contracted by 0.9% on an annual basis in the second quarter, after a 1.6% drop in the first quarter. To be sure, these are only provisional figures, subject to revision. It’s also true that the US doesn’t call recessions based on the narrow, technical definition of two straight quarters of economic contraction, relying instead on a National Bureau of Economic Research committee to serve as umpire. Nevertheless, the GDP numbers felt indicative—of the direction in which the economy is headed, and of a destination everyone wants to avoid.

A host of other signals gesture in that direction as well. Consumers kept some form of economic activity alive, spending more on services in the second quarter. (Hotel and restaurant spending alone moved up by 13%.) But businesses slashed long-term investment, and inflation remains high. The US Federal Reserve hiked interest rates by another 75 basis points on Wednesday, July 27, and did not rule out even bigger increases if needed.

The housing market, in particular, is calling out for attention. New home sales were down for the first half of 2022, and existing home sales have decreased for the past five months. Americans are canceling new home construction, and Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase are laying off employees in their home lending division. The housing market just became the least affordable it has been since the mid-1980s, when the Fed hiked rates to double digits, Black Knight analysts wrote recently. In June, the number of borrowers who missed a single payment rose by 5%, and 90-day delinquencies moved up by 1%, breaking a 21-month streak of improvement.

All of which is to say: It’s understandable if you’re hunkering down, awaiting a recession. But the US may well avoid one entirely. Here’s how.

The backstory

Throughout last year, prices rose and rose. People were spending money again after being unable to during lockdowns, and they felt newly flush with stimulus money. Supply chains were struggling both with demand and covid-induced breakdowns. The resultant chaos from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent the price of oil soaring above $100 a barrel.

Through much of 2021, the Fed thought these high prices were transitory, and

that the supply bottlenecks would eventually ease. But the economy refused to cool, triggering the fastest interest-rate hike cycle in history.

When an economy is speeding along as it was before the hikes—prices high, spending strong—sharp rises in interest rates are the equivalent of smashing the brakes. You hope you’ll slow down safely, but you want, more than anything else, to not go fast any more. There’s always a danger, though, that the economy screeches to a standstill. And hey presto! a recession.

But maybe not this time?

It’s still largely true that US inflation has been stoked primarily by persistent covid lockdowns in China and the war in Ukraine. Supply chain holdups are, in fact, starting to ease now. For these reasons, the economist Claudia Sahm wrote recently, a recession is not inevitable. Moreover, the Fed does not have to fight inflation alone.

“The White House and Congress can help bring inflation down,” Sahm pointed out. “Their tools are more plentiful and precise than the Fed’s.” Encouraging people to work from home and making transit free in cities would all lower gas prices, she noted.

Economists at Employ America, a labor advocacy firm, also suggest that the government set price floors and future sale guarantees for the producers of oil, wheat, and other commodities. This way, producers will not feel the need to charge higher prices now to avoid losses from lower prices later.

The White House has, in fact, accepted one of these proposals—for oil. The government is going to buy oil futures contracts to refill the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). It could do the same for other raw materials that the country’s industries need to function.

Damage to the labor market aside, there are other reasons for Congress and the White House to do more by way of investment. The drop in venture capital funding and initial public offerings, for instance, has meant that biotech companies aiming to advance research and drug development are stalled. Investment in capital expenditures like structures and equipment is also declining, after rising for the first time in more than a decade during the pandemic recovery. These kinds of underinvestments will only make the US economy more fragile to shocks in the future, at a time when it could well have emerged stronger from pandemic.

What to watch for next

- Consumer spending could follow business investment. While businesses are usually the first ones to pull back, the recessionary cycle would be complete once consumers slash their discretionary spending too. That would, in turn, shrink corporate revenues and profits, and increase the number of layoffs.

- Prices will come down. Gas prices fell below $4.50 a gallon in July, a two-month low. The median sale price for new homes dipped by 9% from May to June.

- Higher interest rates. The Fed plans to raise the federal funds rate to somewhere between 3% and 3.5% by the end of the year. If inflation doesn’t come down in response to hikes, then the Fed could raise rates even higher by the end of 2022.

- Supply-side economics. Instead of arguing about the causes of inflation, policymakers in Congress may pass more bills that directly address supply issues. The Biden administration could do away with tariffs or the Jones Act, which bars foreign ships from moving goods between domestic ports.

- Long-term government investment and price regulation. The Department of Transportation is also going to incentivize better land use—denser zoning—using federal funds. The Senate is also considering a bill that would allow Medicare to negotiate the cost of prescription drugs, raise corporate taxes to 15%, and strike the biggest blow to climate change yet with a $369 billion bill that would be disinflationary.

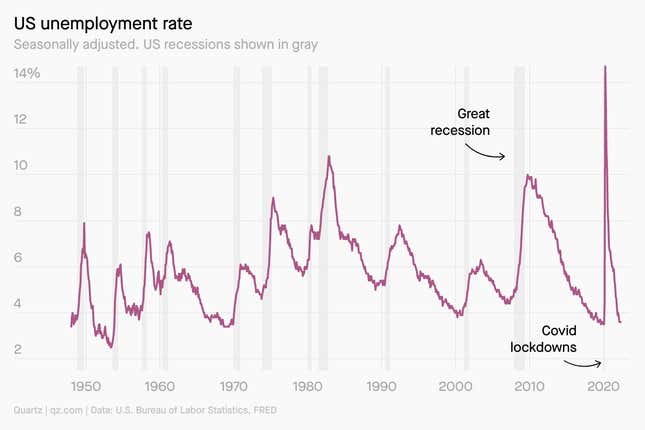

One📈 thing

Is it possible to hit a recession in the midst of a strong labor market? The answer is, it’s not impossible. In the past, the official start of a recession predated the spike in unemployment that comes along with one. Still, with the jobless rate at a historic low, it’ll be a while before the US’s official arbiters call a recession—if they do at all.

Quartz stories to spark conversation

- Why can’t we have legs in the metaverse?

- Inflation is making McDonald’s breakfast a success

- Aspiring midwives of color are mainly motivated by racism witnessed during childbirth

- Congress is finally realizing that clean energy fights inflation

- The critical minerals industry desperately needs new engineers

- Here are all the countries taking a second look at nuclear

5 great stories from elsewhere

💸 Buy future me. The Liberman brothers, Daniil and David, have been “ideas people” circulating in the tech world since the early 2010s, brushing shoulders with everyone from Rupert Murdoch to the Dalai Lama. Now their latest idea is to sell shares in themselves—essentially, letting people invest in their futures. The New Yorker paints a portrait of this dynamic duo who believe that, in an age of mass inequality, buying stakes in people could level the playing field.

⏱️ Too soon to call. With inflation and commodity prices soaring, and global supply chains squeezed between China’s zero-covid policy and the war in Ukraine, many anticipate a recession. But “recessions are hard to spot in real time,” says The Economist, as it looks into indicators beyond GDP, like high confidence in personal finances and a tight labor market, which could actually be causes for optimism in the near future.

🍄 The shrooms race. Psychedelics are having a renaissance. Research has found substances like psilocybin can be used effectively to treat a variety of mental health disorders, sparking a race to corner a market projected to be worth $10 billion by 2027. Wired looks into one company, UK-based Compass Pathways, that is working towards that goal. At the helm is chemist Jason Wallach, who runs a lab devoted to synthesizing new psychedelic compounds.

🌴 Prison in paradise. Lesvos, an island in the Aegean Sea and birthplace of the poet Saphho, has become an “asylum hotspot” designed to keep refugees outside the EU’s borders. In an in-depth policy analysis, Chatham House writes about how the EU’s failing migration and asylum policies go against its humanitarian principles, turning a blue-water paradise into an open air prison.

⚗️ Ancient aromas. Dora Goldsmith is an Egyptologist who studies perfumes from the times of the pharaohs. At Free University in Berlin, she has been able to recreate some of the world’s earliest known fragrances, which ancient Egyptians may have burned as incense, offered to the gods, or even made into a kind of chewing gum. El País talks to Goldsmith about how she painstakingly translates these recipes from pharaonic texts, adding a new sensory dimension to Egypt’s history.

Thanks for reading! Have a recession-free weekend,

—Nate DiCamillo, senior reporter, and Samanth Subramanian, global news editor

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck, Alex Citrin-Safadi, and Clarisa Diaz.