The key to the handcuffs

The FTC wants to kill off non-compete agreements, which prevent tens of millions of American workers from changing jobs

Hi Quartz members,

“Should I stay or should I go?” The Clash once wondered. The song, ostensibly, was about quitting a tempestuous relationship. But it may just as easily have been about a non-compete contract. “If I go, there will be trouble,” Mick Jones, the song’s lead vocalist, agonized. Lina Khan would empathize.

Under Khan, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is proposing a ban on non-compete agreements, which prevent a firm’s employees from moving to another company or starting a business in the same field. It’s a decision that could affect roughly 30 million Americans. Khan, the FTC chair, argued that non-compete restrictions drive down wages and prevent better working conditions. Banning non-competes, she estimated, could increase workers’ earnings by $300 billion per year.

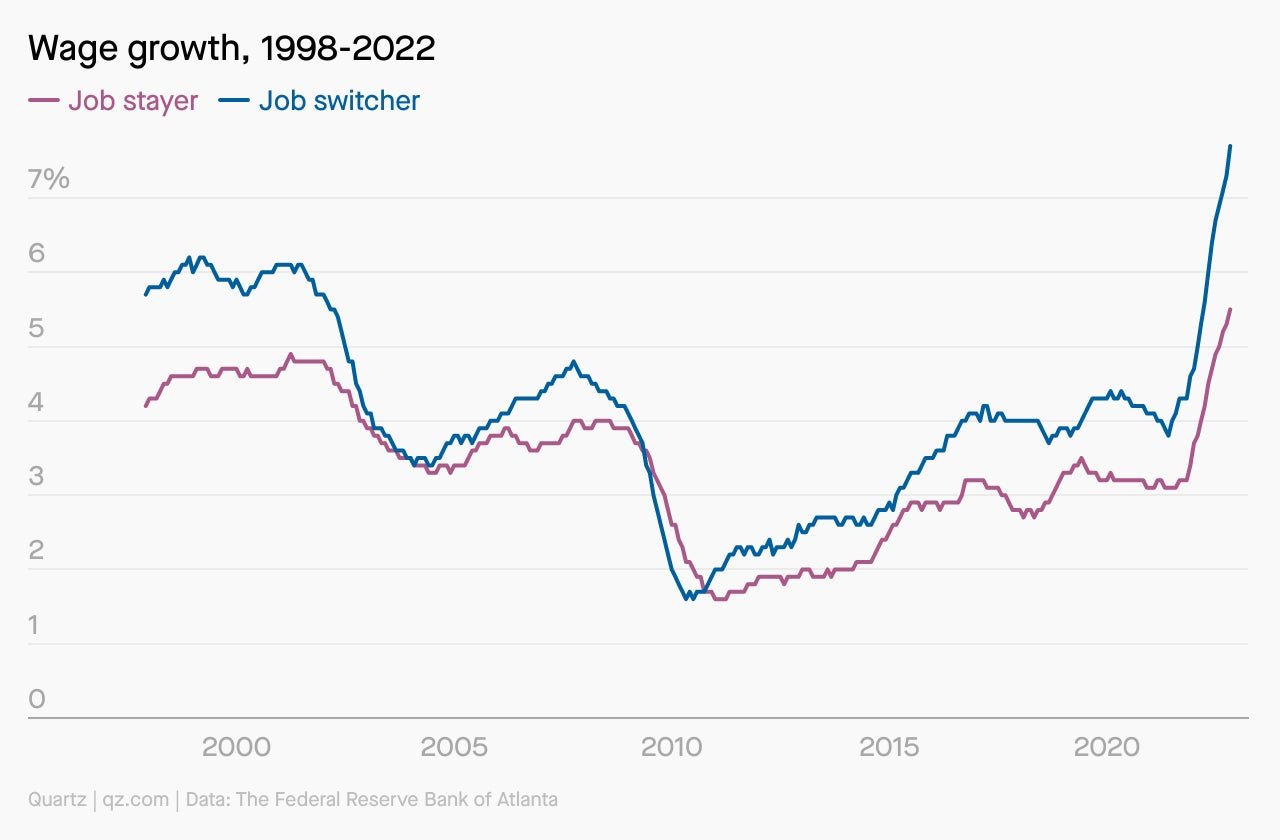

Non-compete agreements depress employee earnings by precluding the wage increases that come from switching jobs. A recent report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that people who switched jobs saw their wages jump 6.7% on average in 2022—2 percentage points higher than those who remained in their jobs.

Even without actually changing jobs, employees can often leverage a competing offer to negotiate a pay raise. But if the employee is bound by a non-compete clause in their contract, their employer is likely to ignore any competing offers, knowing full well that the employee will be unable to leave.

Additionally, studies have shown that industries with high rates of non-compete agreements see a decline in the creation of new firms and start-ups. By reducing the possibility of employees leaving for better situations, competitiveness is dampened, and employees have less incentive to innovate.

The Biden administration sees this potential ban on non-competes as a victory for workers, an investment in a dynamic and innovative economy, as well as a lifeline to millions of Americans stuck in stagnant or hostile work environments. If Khan is successful, this could go down as one of the FTC’s most effective and far-reaching reforms.

THE NON-COMPETITORS

Non-compete clauses are often assumed to apply only to high-ranking corporate executives or those who might hold confidential information about their company. In reality, the average employee working under a non-compete agreement is a middle-class worker paid by the hour. So while corporate executives and tech workers sign non-compete agreements at the highest rates, such clauses can be found in all kinds of professions.

This was illustrated by the FTC’s recent announcement that it will sue three blue-collar companies for requiring workers to sign illegal non-competes. One was a Michigan-based security guard company that prohibited its employees from working for a competing business within a 100-mile radius for two years after leaving. The other two were glass container manufacturers. All three companies settled with the FTC, promising to stop requiring employees to sign non-competes and to void any such agreements with current employees.

Often non-compete agreements for low-wage workers amount to empty threats; most corporations are not interested in a protracted, possibly expensive legal battle against an easily replaceable worker. But non-competes provide an astonishingly easy way to hobble the competition and to intimidate workers. Some websites even advertise free non-compete contracts that take just minutes to draft.

12%: The proportion of workers earning less than $20,000 who had signed non-competes, as of 2014

$100,000: The penalty that a Michigan security firm levied if any of its guards left to join a competing business in a 100-mile radius. (The FTC settled allegations against the company on Jan. 4.)

1 in 3: The number of employees who are presented with non-competes after having accepted their job offers

1 in 10: The number of employees who try to negotiate non-compete clauses

8.6%: The median estimated rise in average earnings for all workers that would ensue if non-competes were rendered unenforceable, according to a 2021 study

ONE 💻 THING

If non-competes had their way, we might’ve never had Silicon Valley.

About half a century ago, the heart of the emerging “minicomputer” industry lay not in Californian sunshine but in Boston’s dim, cold winters. A handful of firms here competed against the PC makers out west. And yet, as the years went on, Boston’s tech sector along Route 128 wilted as Silicon Valley bloomed. What happened?

According to the legal scholar Ronald Gilson, non-competes were at least partly to blame (pdf). California doesn’t enforce non-compete agreements, Gilson argues, which made for a dynamic, open employment culture in Silicon Valley. Companies poached the best, most innovative talent and gave them better resources. Employees quit to strike out on their own. Intellectual property spilled from firm to firm.

These conditions aren’t necessarily replicable, Gilson cautions, either in time or space; a state today couldn’t be certain of conjuring up its own industrial super center simply by doing away with non-competes. But in the legal regime that encouraged the growth of Silicon Valley, one finds another strong argument against the indiscriminate use of non-compete contracts.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- Nearly 99% of US hourly workers earn more than the federal minimum wage

- Dolce & Gabbana is trying to rehab its China image by dressing the wrong demographic

- Closing the gender pay gap has stalled. A new study reveals why

- Seattle schools blame social media for a mental health crisis. Are tech companies liable?

- China wants to corner another segment of the global auto industry: car shipping

- Could you be losing money with a manager title?

- Why an Indian Himalayan town is sinking

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

👵 Grandfluencer. Gen-Z has landed on a new formula for TikTok fame: Let Grandma be the star. The Wall Street Journal interviews several grandkid-grandparent duos that have cornered the “#grandtok” market. Aside from promoting intergenerational bonding, it’s also proven to be a successful business model, with twenty-somethings handling the tech, octogenarians delivering the content, and both splitting the rewards.

🍄 Myco-mania. Mushrooms are popping up everywhere these days, be it on designer runways or in psychedelic brews. By some estimates, the global market for mushrooms will balloon to $115 billion by 2030 as they promise intriguing solutions to mounting technological and mental health problems. High Snobiety talks to people involved in the fungi renaissance, and probes why the chitinous organisms seem to inspire a near-religious devotion.

⭐ Five stars. Google reviews, the go-to spot to check out go-to spots, range from absurd one-liners (“Didn’t enjoy, too much water,” reads one review for the Bering Sea) to touching ruminations (“The peace found in this place is second to none,” writes a reviewer about the lake where their mother’s ashes are scattered). An essay from Longreads examines the humanity, humor, and poetry that are mapped onto locations in this public forum.

⭕ Gather round. For decades, scientists have been puzzled by the mysterious formation of circles in the Namib Desert. But now they may have an answer. A new hypothesis argues that competition amongst plants for scarce water resources (and not aliens) could create the so-called “fairy circles.” The Washington Post talks to desert ecologist Stephan Getzin, who explains the likely reason behind this phenomenon.

🍕 Box flaws. The pizza delivery box was designed in 1966, and as the decades have gone by, its cardboard contours have remained unchanged. That’s unfortunate for us pizza enjoyers, who are left with soggy-crusted, cheese-congealed pies. The Atlantic explores the history of how to deliver a perfect slice, and why it might be time for the favorite order-in meal to get some improved packaging.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have an uncontestably fun weekend,

— Diego Lasarte, staff writer; Samanth Subramanian, global news editor.

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck