Hi Quartz members!

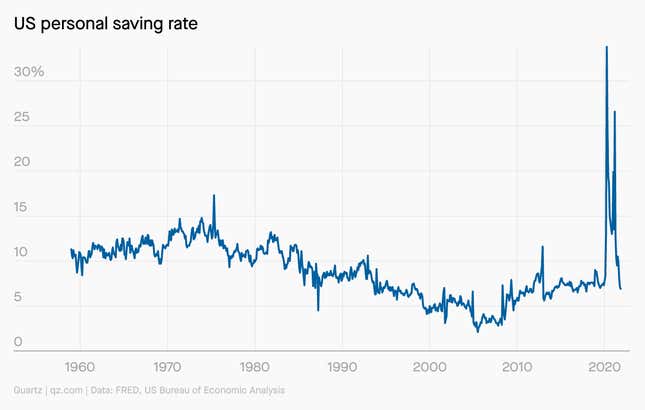

If your New Year’s resolution was to save more money… good luck. This year, more Americans are going to be dipping into their savings as covid-related support from Congress and the Federal Reserve recedes. As of November, workers were already putting away less money than before the pandemic.

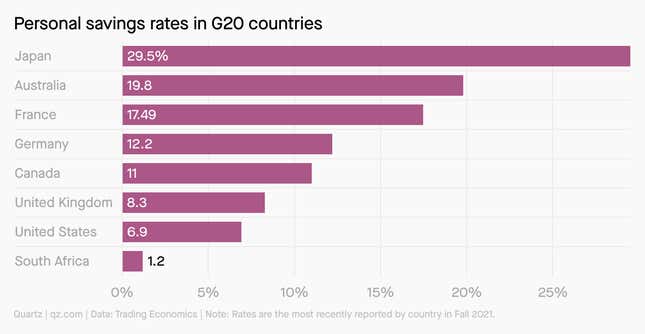

Sturdier savings accounts make both workers and the overall economy more resilient to financial shocks. And for a brief period of time Americans, some of the worst savers among rich countries, socked away a lot more money than they usually do. In this case, the extra savings were the result of weird pandemic circumstances—stimulus checks and fewer opportunities to spend—not financial discipline. Still, they gave Americans wiggle room to find better jobs and tackle financial emergencies that would have previously derailed their budget.

The closest historical parallel is World War II, when the US savings rate shot to 28%. Americans had extra cash then, too: To jumpstart the war effort, the federal government paid workers twice as much as they could spend, says James Galbraith, an economist at the University of Texas.

But that time around, people couldn’t spend because there were fewer things to buy, given government rationing of food, gasoline, and many other goods. As a result, many Americans took payment in the form of long-term bonds. Unlike today, this meant 20- and 30-year-olds in the late 1940s and 1950s could easily afford a mortgage and a family.

Over the subsequent few decades, this wealth and financial security ultimately dissipated. But before it did, it raised living standards for everyone. The pandemic savings surge will clearly be shorter-lived.

The backstory

- Pandemic aid boosted savings. The US savings rate peaked in the summer of 2020, but with most pandemic-related government benefits now expired, Americans will probably be “scraping the bottom of the barrel” by this summer, Galbraith says. “There’s an urge to get back to normal and back to normal is a state of considerable fragility.”

- Extra savings gave workers more leverage. With more cash on hand, workers bargained with their employers by going on strike, unionizing, or quitting. They achieved unprecedented wage increases, and were able to more easily switch jobs. That might seem like it would slow down business, but in the long run it makes workers more productive because they end up in jobs that they’re better suited for, says Alex Williams, a research associate at Employ America.

- The economic recovery has been unusually quick. Once Americans could spend again, consumer demand rebounded quickly thanks to the extra cash buffer. Increased spending increased demand for workers: As of November, there were 1.5 job openings for every unemployed person, giving job seekers more opportunities and signaling a healthier labor market in the future. The Federal Reserve expects the US to hit its target unemployment rate of 3.5% before the end of the year. In 2019—more than a decade after the Great Recession—that target still had not been reached.

The global perspective

Savings rates around the world vary depending on economic growth, incomes, and taxes. In general, countries with low taxes have higher gross domestic savings rates. (Oil-rich countries also have higher savings rates.) Compared to other G20 countries, the US personal savings rate ranks near the bottom.

What to watch for next

- Poor people lose their financial cushion. The majority of extra savings are held by rich people, says Wendy Edelberg, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution; lower-income households increased checking account balances by about $500 during the pandemic. The JPMorgan Chase Institute estimates that seven weeks of savings—or roughly $2,500—is needed as a cash buffer for low-income families.

- Child poverty goes up. Parents are particularly attuned to the need for short-term savings, but Democratic senator Joe Manchin may have permanently killed the Child Tax Credit that expired last month. Millions more children are expected to go back into poverty in 2022. “We knew the end of fiscal relief was coming, and it would be hard,” says former Federal Reserve economist Claudia Sahm. “We did not expect covid would come roaring back again, and Manchin would block the extension of the Child Tax Credit.”

- The labor shortage turns into a lack of labor demand. Some 80% of excess savings during the pandemic went to the top 20%, who tend to spend their savings more slowly and stimulate the economy less than poor workers. Omicron also has the potential to keep more people at home, to reduce consumer spending, and to dent the demand for labor.

- Job-switching slows down. Contrary to popular belief, dwindling savings won’t spur people to find more work, says Kate Bahn, interim chief economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Having more money in the bank actually gives low-income workers the ability to conduct job searches when they need to, and match into better paying jobs.

- A return to credit card dependency. As savings begin to dwindle, credit card debt is rising again. When the Fed starts to raise rates, there may be another period of rising debt where some consumers take out new loans to cover existing loans with increased interest rates. Their savings rates will dip further.

One 📊 thing

Excess savings can tell us how successful the stimulus was and what the future of the economy might look like, but we need better data. The US doesn’t frequently report the savings rate by income distribution, and data from the private sector is biased towards consumers with bank accounts, which means poor Americans’ excess savings could be overestimated. With this blindspot, policymakers may be underestimating how much support workers actually need and how resilient the economy will be to future shocks.

Quartz stories to spark conversation

🇨🇳 Beijing’s digital yuan app is getting Olympics-ready

🏥 US hospitals are breaking the law on price transparency

📈 The top-performing commodity of 2021 rose 437%

🤔 GameStop wants to sell you NFTs

📋 Can algorithms be regulated? China says yes

🚘 American millennials just aren’t that into driving

🩸 The Theranos trial was a pop culture phenomenon

5 great stories from elsewhere

🔥 This world is on fire. The New York Times Magazine laments the growing climate hazards of living in California, and humanity’s need to be more “trans-apocalyptic.”

🏥 There’s a hospital bed monopoly. The American Prospect digs into the company that controls 75% of the hospital bed market, and its ruthless quest to thwart rivals.

♻️ The plot against green investment. The New Republic looks at lobbying efforts to fight the financial institutions that are disincentivizing fossil fuels.

🏈 How Biogen fumbled its Alzheimer’s drug. After promising early results, the pharma company raced toward regulatory approval. As the Wall Street Journal reports, that’s when things got confusing.

🏠 The story of the Steel House. Texas Monthly documents the saga of an iconic artist-built house east of Lubbock, now being turned into a controversial Airbnb.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a thrifty weekend,

—Clarisa Diaz, multimedia reporter (saying goodbye to her savings)

—Nate DiCamillo, economic reporter (keeps his in a piggy bank)