Hi Quartz members,

The word is clumsy enough: “friendshoring,” a portmanteau buzzword for the business strategy of running supply chains only through countries that are close political partners. As a concept, though, it’s even clumsier—and damaging to the world’s economy.

Politics and covid-19 have made the last two years hard on supply chains. China’s political decisions to institute hard lockdowns led to global shipping and manufacturing delays. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to wheat shortages, and the need for Europe to suddenly reorganize its energy supply lines. The US and EU are both investing in semiconductor manufacturing plants at home to reduce their reliance on Taiwan, an island politically vulnerable to China.

Given how politics puts critical supply chains at risk, it’s little wonder that corporate and political leaders have begun to ask whether friendshoring would make those chains more resilient. If Europe buys gas and rare earths from the US and in turn supplies Australia and Canada with semiconductor chips, surely these links will weather political storms better than those reliant on Russia or China.

That is, at least, the theory behind friendshoring. In practice, it will be an entirely different matter.

How friendshoring is bad for business

- It’s regressive. Three decades after the Cold War, it’s easy to forget that the world once friendshored by default. The US and the USSR had their spheres of influence, forcing countries to align with one bloc or another; the promise of the end of the Cold War was more openness. Friendshoring will mark a retreat to fragmentation, IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva said at Davos recently, “with trade blocs and currency blocs separating what was up to now still an integrated world economy.”

- It will harm poor countries. The process of globalization has had its drawbacks, but among its economic effects has been the growing prosperity of developing countries that participate in the world economy. Friendshoring will “exclude the poor countries that most need global trade in order to become richer and more democratic,” economist Raghuram Rajan wrote recently. “It will increase the risks that these countries become failed states, fertile grounds to nurture and export terrorism.”

- It will force prices up. For a long time now, the global economy has been arbitraging costs of labor and production to provide us with cheap devices, clothing, household goods, and much else. If this disappears—if the West, for instance, largely sources materials and components only within its bloc of nations—costs will rise dramatically, stoking social discontent. In trying to elude the effects of global political risk, friendshoring will have ended up creating new kinds of political risk at home.

- It’s harder than it looks. The supply chains that seemed so vulnerable over the past two years are also more robust than we give them credit for—and therefore harder to restructure than we think. When the Wall Street Journal broke down the supply chain of a hot tub, it found that the company assembling the tub in Utah was using 1,850 parts from seven different countries. Redoing these supply chains so that they flow only through the Western world will be difficult and costly.

Numbers for your next chat

📱 How complex are today’s supply chains? Apple currently buys iPhone components from 43 countries on six continents.

🤑 A few years ago, research firm IHS Technology estimated that an iPhone 5, which then retailed for about $800, would cost nearly $2,000 if it was made entirely in the US.

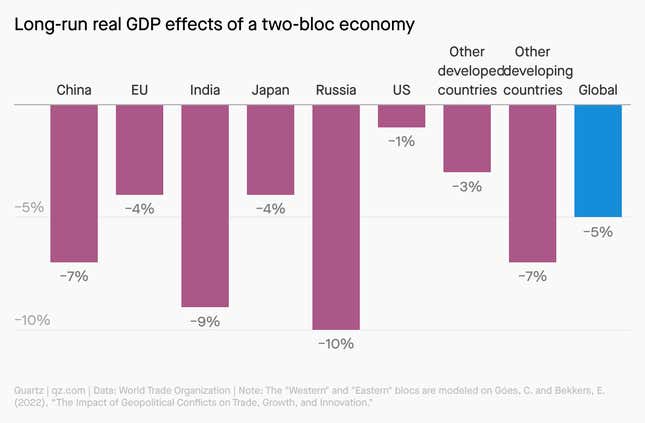

📉 A World Trade Organization (WTO) study (pdf) of the Ukraine war estimated that the global economy decoupling into “Western” and “Eastern” blocs would cost it nearly 5% in output, the equivalent of more than $4 trillion.

🌍 In the WTO’s decoupled-economy model, the US loses 1% in economic output, while India loses 9% and other developing countries lose 7%.

What to watch for next

- Inventory levels. The world has turned so variously unpredictable that companies will start to keep bigger stocks of components and products, to have them at hand just in case a supply chain goes awry. One survey of 200 businesses in the UK and Ireland found that 85% of them are already beginning to do this.

- The return of non-alignment. During the Cold War, many countries in Asia and Africa declared themselves “non-aligned”: unwilling to be part of either the Western or the Soviet bloc. If any new blocs form, will nations—particularly in the developing world—decide again that their best economic interests lie in dealing with both sides?

- Reshoring. What’s more robust than a supply chain that runs through other friendly countries? A supply chain that runs only through your own country. Expect plenty of endeavors along the lines of the push to bring more semiconductor chip manufacturing back to the US.

- The EU’s oil sources. Having agreed to ban almost all Russian oil imports by the end of the year, the EU will now have to friendshore its oil supplies. Middle Eastern countries like Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are expected to make up the shortfall.

One 🤝 thing

Who came up with “friendshoring”? In 2019, Newsweek cited Bonnie Glick, then-deputy administrator of USAID, for coining “allied-shoring”: same concept, and arguably just as ghastly a word. But “friendshoring” first appeared (pdf) in a White House report in June 2021. To build more resilient supply chains, the report said, tools such as “ally- and friend-shoring, and stockpiling, along with investments in sustainable domestic production and processing will all be necessary.”

Quartz stories to spark conversation

⚖️ Is student loan forgiveness fair to everyone else?

📉 The strong labor market doesn’t mean a recession is inevitable

🙃 Elon Musk wanted more data, so Twitter gave him all of it

📅 Pakistan’s energy-crunch solution is a shorter work week

💸 NYC landlords are rejecting tenants making under $160K

🛢️ Most economies are slowing down—except oil producers

🚇 Should commute time be counted as part of the workday?

☣️ The real reason toxic leaders keep getting promoted

5 great stories from elsewhere

😤 NIMBY v. YIMBY. Susan Kirsch has spent 20 years fighting housing developments in her suburban California neighborhood, making her a bit of a “NIMBY,” or “not in my backyard.” In a profile of the archetype, the New York Times explores a nuanced disconnect between hardline NIMBYists’ progressive politics and their inequitable stance on housing.

🏞️ A river in crisis. The Colorado River cuts through seven US states, provides drinking water for tens of millions, and holds both agricultural and ecological significance. But the river is losing water due to rising temperatures. Winding along its 1,450 miles, the Washington Post compiles stories and photos that document the fallout from a shrinking waterway.

🤡 Know your memes. You can hold multiple slurp juices on a single ape, and if you have no idea what that means, you can look it up on KnowYourMeme.com. In a conversation with Cybernaut, KnowYourMeme editor in chief Don Caldwell talks about how to screen memes, the evolution of the genre, and the explosive memetic force that is TikTok.

📱Who’s to blame? Social media gets charged with many crimes, not least the destruction of society and our brains. Surely inspired by an abundance of think pieces, The New Yorker turns to research to determine whether Twitter and its ilk are indeed catalysts for echo chambers, misinformation, and radicalization. The results are as nuanced as social media is sensational.

😩 AHHHHHH! From the Beatles to BTS, fangirls have earned a reputation for unleashing deafening shrieks upon seeing swoopy-haired boy groups. In The Atlantic, the author of a forthcoming book on the subject argues that these teenage screams belie the creative, transformational communities of online fandom.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a yes-in-your-backyard weekend,

—Samanth Subramanian, senior reporter

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck.