When can you fly me?

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: The race to launch the smallest satellites is heating up, an orbital game of catch, and how space science undermines authoritarians.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Nearly three years ago, I reported on the competition to be the leading launcher of small satellites. With hundreds of millions invested in small satellite companies, somebody had to get the darn things into space. Big rocket companies were focused on big satellites, creating a market opportunity for someone to care about the little guys.

A lot has changed—now there are more than 130 small rocket launch companies in the world, and the majority of them are not going to survive the coming reckoning. The shots were fired this week at the Small Satellite conference in Utah.

First, the big rocket companies are paying more attention to the market. After a 64-satellite mission last year, SpaceX now says it will do a dedicated ride-share mission for small satellites in each of the next three years, at a cost of roughly $15,000 per kilogram of payload. That’s bottom-barrel pricing for space launches. The Russian space agency quickly announced they would charge the same for small satellites launched on their Soyuz 2 rocket. And Europe’s Arianespace announced it would have a dedicated small sat flight, too.

Among the new small launchers, only one is actually operational—Rocket Lab, the US-New Zealand firm that has flown six successful missions since January 2018. Its charges customer more than twice as much per kilogram, but the offering here is flexibility and timing: Rocket Lab expects to launch at least once a month, not once a year, and to a variety of orbits.

Peter Beck, Rocket Lab’s CEO, tells me he’s not worried about the big rocket companies getting more serious about his market. “When we sit down with a customer, the first question is when can you fly me? The second question is, how much?” he says.

SpaceX’s single rideshare flight a year won’t be enough to trouble Beck’s business. He does say it might spell trouble for other rocket companies aiming for the middle ground between his Electron rocket, which carries 150 to 225 kilograms, and rockets like SpaceX’s Falcon 9 that can carry many tons of cargo.

Beck and company aren’t resting on their laurels, however. The second big news this week is that Rocket Lab will work to make the first stage of its Electron reusable, which is already virtually a requirement for next-generation large rockets.

That’s an about-face for the company, which had previously said that investments in reusability were too costly for their minimum viable product. Now Beck says that data collected on the vehicle’s first flights showed that it is robust enough to survive re-entry. More importantly, he says he just can’t build rockets fast enough to keep up with the demand.

If his team can figure out how to make sure their rocket survives an 8.5 mach trip back into the atmosphere, snag it with a helicopter and then refurbish it, they’ll have doubled their production rates.

“Launch frequency is the thing that is going to change this industry,” Beck said during his reusability announcement—a higher cadence means lower prices and more innovation. Now, they just have to make it happen.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery Interlude: A high-stakes game of catch succeeds: SpaceX’s Ms. Tree vessel successfully catches half the nosecone, also called a fairing, that separated from a Falcon 9 rocket hundreds of miles above the Earth after an Aug 6. launch. It’s just the second time the maneuver has been pulled off.

SpaceX has been working to recover fairings since 2017, in the hopes that they can be re-used. Elon Musk has compared the effort to catching a palette of money falling out of the sky, since manufacturing the ultra-light and ultra-strong nosecones costs $8 million. If the company is able to re-use the fairings in the future, it will be one more avenue to drive down the cost of their rockets.

🚀 🚀 🚀

PROMOTION TIME!

I want to hear more from you, readers, and I’m willing to make it interesting. Let’s keep it simple: Reply to this e-mail with the most important question in space business today. Everyone who responds will be entered in a drawing to win a copy of my book Rocket Billionaires and a 50% discount on Quartz membership (arguably the better value). Also, I’ll try to answer the questions!

🚀 🚀 🚀

SPACE DEBRIS

Brazil nuts. The head of Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research was fired last week for telling the truth about the rapid pace of illegal deforestation in the Amazon. Ricardo Galvão defended his agency’s satellite research, which showed a 60% increase in forest clearing since right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro took office. Bolsonaro called the findings “lies,” but the agency’s work is widely respected by the scientific community. Mockingly called “Captain Chainsaw,” Bolsonaro is backed by mining companies and agribusiness and has argued for more development of the rainforest—just as long as nobody notices, apparently.

Go or no go? With William Gerstenmaier ousted, someone new will be in the hot seat when it comes to final authorization for NASA’s riskiest astronaut missions. Ars Technica’s Eric Berger looks at how difficult it will be to replace him with someone who has the technical chops to earn the trust of the space agency’s workforce. Ensuring that technical concerns get communicated up the chain of command and properly evaluated has been a challenge at NASA, highlighted by the Challenger and Columbia disasters. Gerstenmaier helped implement reforms after Columbia aimed at fixing that problem, and his successor will need to be able to balance engineering reality and the willingness to take risk.

More small sat cash. HawkEye 360, a firm building a network of satellites to gather radio-frequency data, announced a $70 million series b financing round this week. The company plans to launch 18 satellites that will do things like pinpoint the location of ships and track emergency distress beacons. Its backers included venture funds and Airbus, the European aerospace giant.

Water (Bears) on the moon. WIRED’s Daniel Oberhaus broke the space story of the week when he revealed that the crashed Israeli Beresheet moon lander carried, besides a digital library and scientific sensors, a bunch of microorganisms called tardigrades. These unusually hardy little guys, also called Water Bears, can survive in the most extreme environments—including, maybe, the moon. The good news is that the tardigrades in question are in a dehydrated hibernation state and would need to be rehydrated in an atmosphere to become active creatures again. But NASA takes not contaminating other astronomical bodies with Earth organisms pretty seriously. A private organization launching creatures to the moon without checking in with, um, anyone, raises big questions about what kind of rules should be in place as the cost of getting into space—and onto the lunar surface—continues to fall.

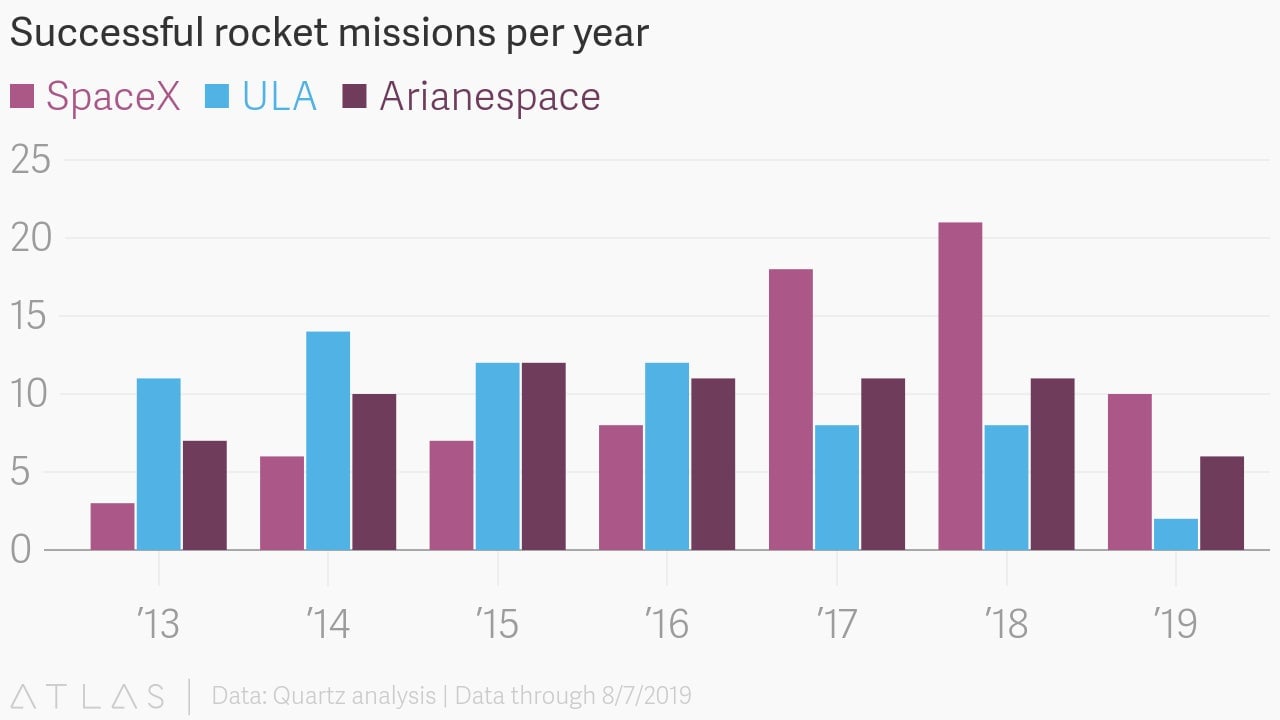

Launch activities. This week we’re expecting launches from all three Western major rocket-makers. Arianespace went first, SpaceX went next, and if all goes to plan ULA will have flown a satellite for the US Air Force shortly before you receive this newsletter. Here’s the current launch leaderboard:

your pal,

Tim

This was issue 10 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your dang questions, satellite evidence of government wrong-doing, tips and informed opinions to [email protected].