Over the moon

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: The latest on Moon 2024, Jeff Bezos challenges the Air Force and the first Emirati astronaut.

🌘 🌘 🌘

I know you’re all closely following the most important political developments in Washington—by which I mean, trying to figure out if NASA is actually launching a mission to return to the moon in 2024.

(What, there’s something else going on? Oh, right. Yes, an impeachment process that could derail the Trump administration’s space plans.)

Even without political calamity, it doesn’t look like my earlier pessimism about the Artemis program was misplaced. First, Congress is now delaying its 2020 budget decision until the end of November, so NASA won’t get the money it needs to build necessities like a lunar lander for another two months.

Six months ago, when this plan was launched, one aerospace engineer told Ars Technica’s Eric Berger that his company would need to start on a lander “today” to make a 2024 deadline.

Since then, Democrats in the House of Representatives declined to fund the moon plan. Would the Republicans in the Senate be more generous? This week, we found out the answer is “no.” Their NASA budget provides less than half the amount NASA requested as a down-payment on its lunar return.

This comes after administrator Jim Bridenstine spent most of August on a whirlwind national tour, visiting lawmakers’ home districts to drum up support. The result? “I’ve yet to see the numbers for a five-year plan,” senator Jerry Moran, the Kansas Republican, told the Washington Post’s Christian Davenport. “I want to be able to strongly make the case for acceleration for Artemis, for moving forward with landing a woman on the moon. But for me to convince my colleagues, I need information I don’t yet have.”

One reason there are no numbers is that there is still no permanent NASA executive leading the human-exploration program. The acting leader, Ken Bowersox, testified last week that “I wouldn’t bet my oldest child’s upcoming birthday present or anything like that” on meeting the 2024 deadline.

Bowersox argued that an aggressive goal would be smarter for NASA, even if the actual deadline is missed. Yet there’s a risk that the push to meet the deadline will overwhelm the other goals of the program. Scientists and space advocates hope to lay the groundwork for a longer-term lunar presence, learning about the moon’s resources and using it as a base for new astronomical observations.

But if the date trumps all, then political pressure could lead to Apollo redux: A push to get boots and flags in the regolith, and forget the research. Boeing, for example, is pushing NASA to abandon plans for multiple commercial rockets and a gateway station orbiting the moon, urging the agency to spend more upgrading its SLS rocket so that astronauts could go straight to the moon. That architecture could achieve the administration’s political goals, but wouldn’t leave behind the infrastructure for sustainable long-term presence.

As far as industrial policy goes, NASA is doing OK: It announced that Lockheed Martin received $4.6 billion worth of contracts with guaranteed profits to build six Orion spacecraft for the moon program. Jeff Foust noted the subtext spotted by space watchers: Three Texas lawmakers who had previously criticized the Artemis program were quoted in the news release, talking about how the new contract would benefit their home state.

🛸 🛸 🛸

Imagery interlude

Sometimes the wildest space scenarios are what might have been. Wayne Hale, a former NASA official who spent five years running the space shuttle program, shared a story about a truly ridiculous kludge used by the vehicle.

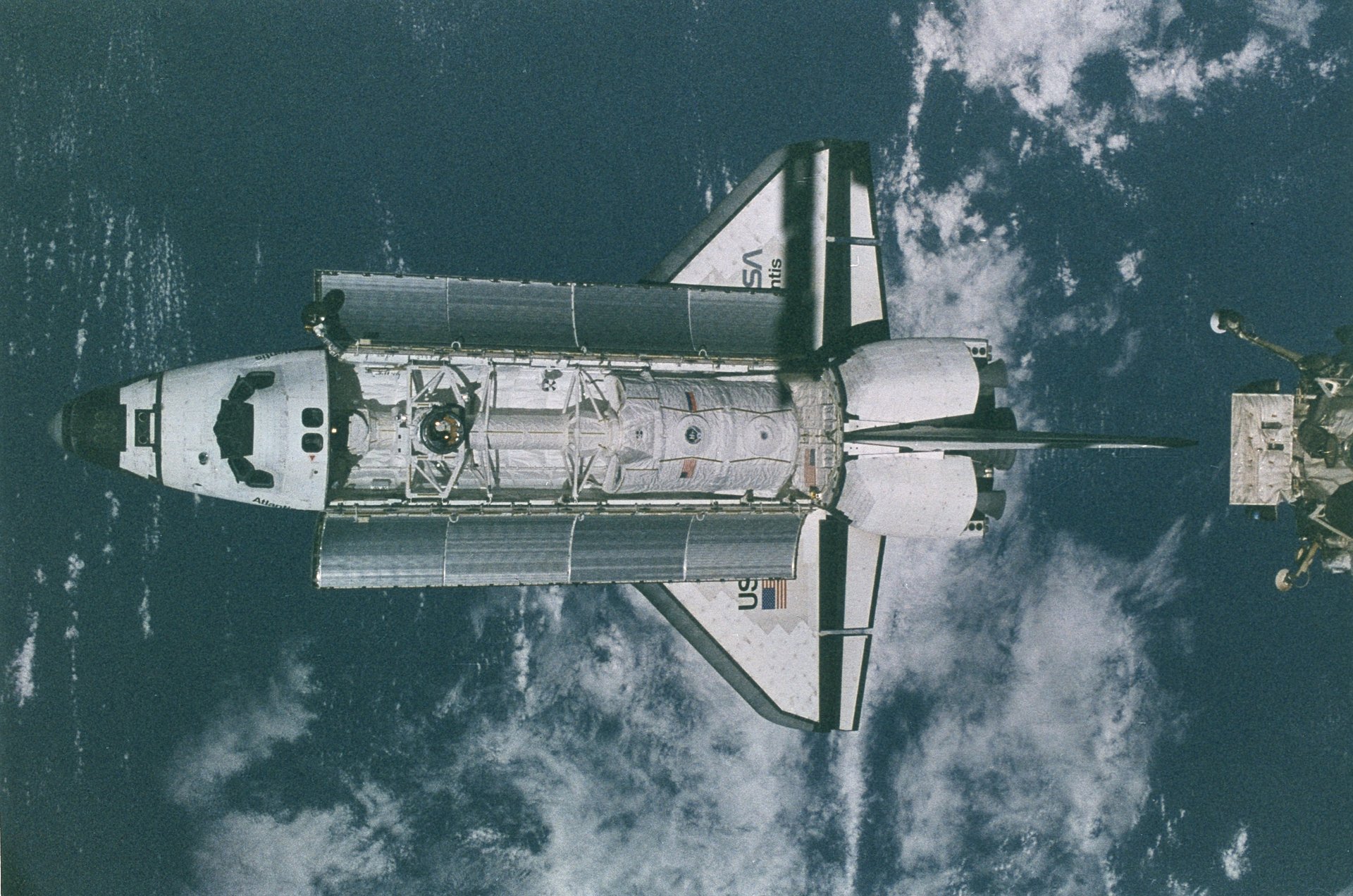

The shuttle had to close its payload bay doors before flying back to Earth. If the doors jammed, a space-suited astronaut could climb back and manually secure them. But when NASA began flying a large research module called SpaceLab, the shuttle team realized that if the payload doors had to be manually closed, the astronaut would be trapped in the back of the shuttle—and have to ride home there. Here is SpaceLab inside Space Shuttle Atlantis in 1995:

The trip down would have been fairly safe, Hale writes, but “getting the crew member out of the payload bay, well that is a problem. Remember the doors are latched shut and clamps have been applied to keep them shut. Surely the ground crew could figure something out . . . given several hours…So that is the story. Accept the risk because we think it is low; have a screwy contingency procedure ready if we’re wrong.”

🚀 🚀 🚀

SPACE DEBRIS

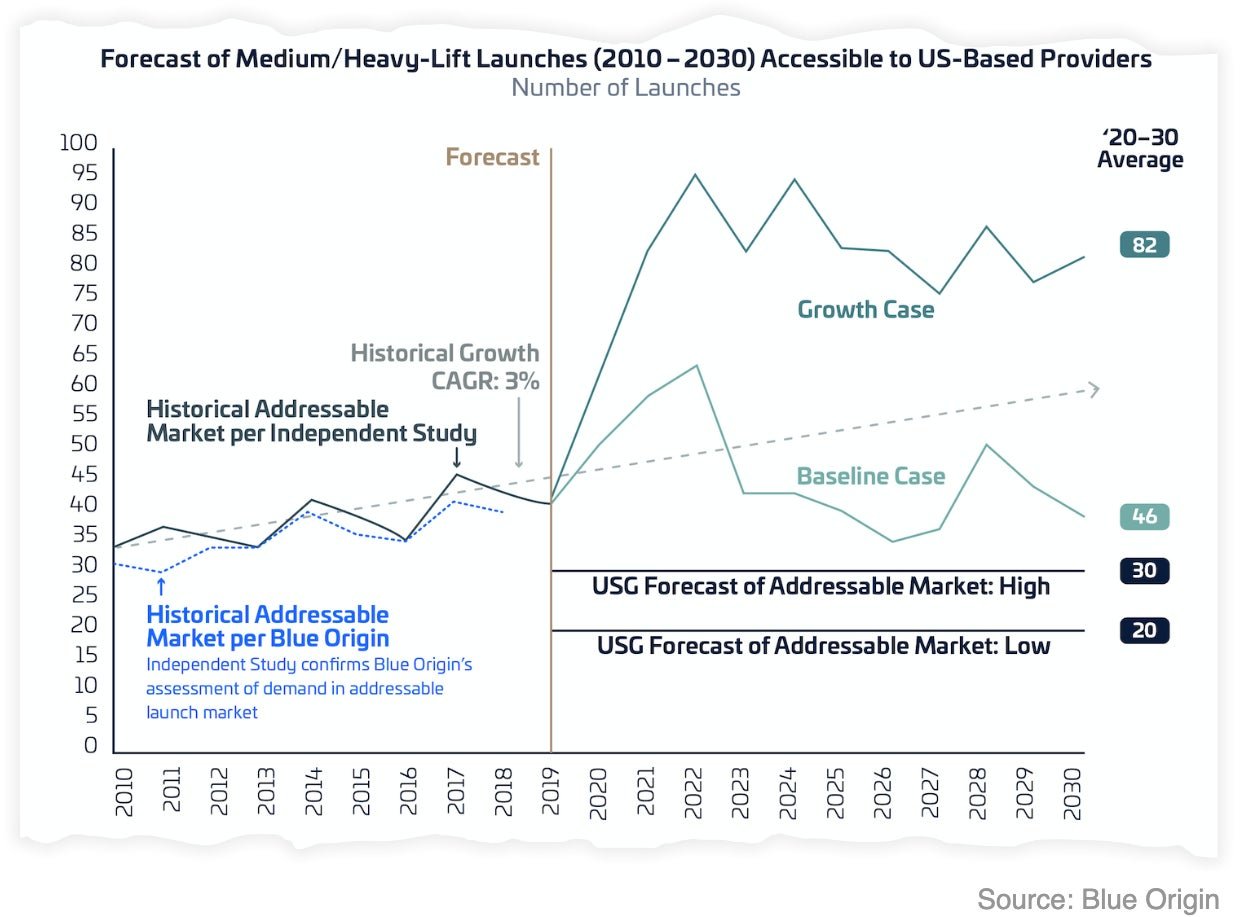

Jeff Bezos wants the US Air Force to think big. The fight over the next generation of military rocket contracts will shape the US space program for a decade. There are plenty of complaints about how the Air Force is running the procurement, but Jeff Bezos’ space company Blue Origin launched a media blitz this week to point out that things have changed since the last time the Pentagon went to the rocket store. Today, CEO Bob Smith argues, space is important enough to sustain at least three US rocket-makers, and the Air Force shouldn’t be in the business of deciding which private businesses are commercially viable.

The NEOCam Mystery. This summer I spilt some ink about how NASA ignored a recommendation from the National Science Foundation to fund a space telescope called NEOCam to hunt for asteroids that could potentially endanger earth. On Monday, NASA’s top science administrator, Thomas Zurbuchen, said the agency would launch a NEOCam-like mission. So what’s changed? NASA public relations hasn’t responded to repeated inquiries. I’m accepting your theories!

Space debris spat. Figuring out the right regulatory approach to the problem of space junk is no easy task, given the way authority is scattered through several space-related agencies. Now, we have some idea why it’s taken a year for US government’s working group to release four pages of guidance: NASA and the Department of Defense have been sparring over exactly what those rules ought to be.

UAE to LEO. Hazzaa Al Mansoori, the first astronaut from the United Arab Emirates, launched to the International Space Station for an eight-day mission yesterday. Mansoori, a former fighter pilot, will spend his time on the ISS performing scientific experiments with colleagues from Russia, the US and Italy. The UAE’s space agency was only founded in 2014, but it has big ambitions—and notably, the petroleum industry to fund them.

Developments at the development agency. The US Space Development Agency, set up this year to help develop new orbital technology for the military, is pushing through some growing pains and re-designing the new satellite constellation it wants to launch in the next few years to spy on rivals. We’ll be watching to see if the plan survives the political fight around Space Force and who in the Pentagon will control space-research budgets.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 16 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your NEOCam gossip, nominees to lead NASA’s human-exploration program, tips and informed opinions to [email protected].