Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think.

This week: US export controls stand in the way of space supremacy, Rocket Lab’s first US launch, and Boeing’s big losses.

🚀 🚀 🚀

What fuels American technology supremacy? One key factor is immigration.

In the 1930s, a group of Hungarian geniuses fleeing repression in Europe—including Edward Teller, John von Neumann, Theodore von Kármán and Paul Erdős—came to the US and were cheekily known as The Martians after revolutionizing a half-dozen scientific fields. More controversially, German scientists who served the Nazi regime became important players in the early days of NASA.

In today’s world of global technical competition, openness to immigration is an enabler of success. I can dump a dozen studies on your desk that show things like 38% of American Nobel Prize winners are foreign born, or that 36% of US innovative output comes from immigrants, or that immigration to the US since 1965 increased innovation 8% and real wages by 5%. Or you can look at individuals: Indian-born Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, South African-born SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, or Russian-born Google co-founder Sergei Brin, all working in the US.

While much of the US tech world is driven by engineers and business people with global backgrounds, hiring foreign nationals is much more difficult in the space tech sector. Just about everything related to rockets and spacecraft is considered a dual use technology with both civil and military applications and restricted to US citizens or permanent residents. That has led to blow ups, like former Momentus founder Mikhail Kokorich, a Russian national, being ousted from his company. And the situation causes grief for aerospace engineers around the world who want to get in on the ground floor of the new space industry in the US.

Late last year, Enzo Bleze and Nick Orenstein, founders of HStar Space, argued the US should link reforms of its temporary work visas and International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) that govern technology access. Even if more foreign nationals can legally work in the US, they would likely not be able to work in the space sector. Even clarifying the rules to allow more exceptions for fairly banal space tech would be helpful. Meanwhile, US agencies are fretting about whether the US space industrial base can remain competitive with China. One obvious way to compete is to make sure the most talented scientists and engineers in the world can come here.

This competition is already happening on the civil side of space: China’s new space station will vie with the International Space Station for global participation in space science. Meanwhile, this week SpaceX is set to launch astronauts from the UAE and Russia, alongside two Americans, to the ISS. While NASA has a framework for letting those foreign nationals train on commercial crew vehicles, it’s running into issues bringing foreign partners to work on projects related to the Artemis lunar return. That’s a real problem for a program that is billed as an international effort and could benefit from more cost-sharing.

The overall trend for US immigration hasn’t been good in recent years: The number of immigrants grew more slowly in the last decade than in the 1990s or early 2000s. In 2021, the US government failed to issue around 66,000 of the 262,000 available permanent residency cards simply because of poorly functioning bureaucracy. That included green cards for more than 15,000 applicants considered exceptional due to advanced degrees or other qualifications.

Immigrants, particularly skilled ones, have been consistently shown to improve economic outcomes in the US. The major argument against allowing more foreign-born people to work on dual-use technology is the fear of espionage and theft. Consider that the Manhattan project to develop the atomic bomb, which relied on the Martians and many other foreign nationals, was penetrated by Soviet spies—but having the team of geniuses was significantly more advantageous than any damage caused by a few spies among them. The same is likely true in space and other frontier technologies, from AI to electric cars.

🌕🌖🌗

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

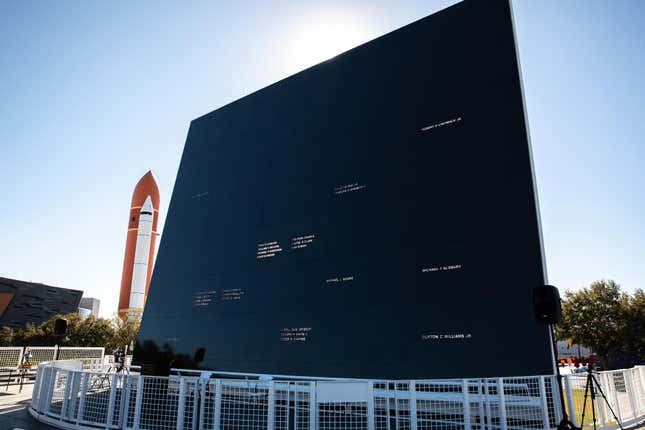

Today, NASA will mark its Day of Remembrance for those who lost their lives furthering the cause of space exploration. That includes the crews of Space Shuttles Challenger and Columbia, and the three Apollo 1 astronauts who died during a test accident. Their names are inscribed on the Space Mirror monument near Cape Canaveral, Florida, shown below.

Consider reading an excerpt from my book about how the Columbia tragedy led to the age of commercial space, or for the more technically-minded, this discussion of how NASA’s risk analysis evolved (pdf) during the Apollo program.

SPACE DEBRIS

Rocket Lab’s first US launch succeeds. An Electron rocket took off from Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia on Tuesday (Jan. 24), delivering three HawkEye360 satellites to orbit. Breaking in the new launch pad should mean more flights for Rocket Lab (NASDAQ:RKLB), which also operates a launch site in New Zealand.

Boeing, a surprise loser. The US aerospace conglomerate (NYSE:BA) reported a surprising $650 million loss during the fourth quarter of 2022. Most of the bad news came from the company’s aviation division , but the company’s defense and space division lost $3.5 billion in 2022. While details are not broken out, we know Boeing lost $288 million last year alone trying to catch up its delayed Starliner program.

Starship pulls off a wet dress. The SpaceX Starship rocket and its Super Heavy booster were fully stacked and fueled during a so-called wet dress rehearsal in Boca Chica, Texas. The run-through is another step toward an orbital test flight; up next, we’re expecting an engine test, firing up all 33 of Starship’s engines on the launch pad.

The Pentagon is learning. At this week’s National Security Space Association’s defense and intelligence conference, US military leaders recognized that geostationary satellites are too immobile to be safe and the days of buying large, bespoke satellites are over. One reason why? The increasing evidence of threats to those vehicles, such as the release of a small spacecraft in geostationary orbit by a Chinese satellite.

Asteroid miners prepare for launch. AstroForge, which wants to pluck platinum-group metals from near-Earth objects, plans to launch a payload in April that will demonstrate the ability to mine metals in space. The company also expects to launch another spacecraft onboard Intuitive Machines’ lunar mission later this year that will fly to a target asteroid and assess its viability for future mining.

A big step toward nuclear spacecraft. NASA and DARPA, the military’s advanced projects lab, are teaming up to develop nuclear propulsion technology, with a test planned for 2027. Rocket scientists believe nuclear-powered engines could make inter-planetary space travel more realistic, but developing such technology safely is a major challenge.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 166 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your schemes to reform US export controls, use cases for nuclear propulsion tech, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].

Correction: This newsletter erroneously referred to a launch site as Wallops Space Center; the NASA launch facility is correctly named the Wallops Flight Facility.