Space Business: Impact Statement

Can the US build new spaceports under modern environmental regulations?

Whenever China launches a rocket and drops dangerous debris in a populated area, Western observers tend to feel superior because US and European launch sites are meant to adhere to stricter safety regulations and a bias toward public opinion. This is helpful context for the debate over SpaceX’s Starship launch site in Boca Chica, Texas.

Suggested Reading

The recent test flight there was another step toward a vehicle that could unlock the potential of the space economy. But it revealed some clear problems with the way the brand new site has been designed. Now, a coalition of environmental groups is suing the Federal Aviation Administration for failing to force sufficient environmental review of the launch site.

Related Content

Set aside your feelings about Elon Musk and SpaceX: If China had flown a Long March 5 rocket from a new launch pad and covered towns miles away in a coating of dust and pulverized concrete, would you say it’s business as usual, or amateur hour?

Before the Boca Chica launch site was approved by the FAA last year, there were vociferous debates among rocket fans, the local community, and environmental groups about whether the launch site belonged there. A seaside location close to the equator ideal for launching rockets isn’t easy to find in the continental US, and the community could use high-paying jobs. But was the area, which included wildlife refuges, marshland, and a historic Civil War battle site, the fitting spot for the world’s largest rocket?

After a long process of filings and public comment, the FAA issued a “Finding of No Significant Impact” (FONSI) that allowed SpaceX to apply for and eventually receive a license to perform test launches at the site. But the new lawsuit revealed something interesting: In 2020, an FAA official wrote in an internal email that SpaceX should create a full Environmental Impact Statement about its plans for the site, a more costly and time-consuming exercise, before instead allowing SpaceX to avoid that route by obtaining the FONSI.

Critics have a point when the say the engineering analyses underlying the no-impact finding appear to be off the mark. For example, Eric Roesch, an environmental compliance expert, has written that attempts to model the noise and exhaust of the rocket engines were based on a vehicle 20% less powerful than the one that was actually flown, which might explain why debris was thrown far beyond the area expected by the agency. And Musk himself said that the decision to launch without a flame diverter was driven by analysis of a static fire at 50% thrust.

Should engineers have anticipated more consequences during a full-thrust launch? During that same static fire test, a US Fish and Wildlife Services employee measured sound that exceeded noise limits expected during a regular launch.

The crux of the lawsuit is that the no-impact finding is only meaningful if SpaceX follows more than 75 mitigation requirements included in the document. But the plaintiffs say those mitigations were either ineffective or not followed, leading to trouble. When Quartz asked the FAA before the launch if SpaceX had accomplished them all, the agency declined to answer specifically, but said it “will ensure SpaceX complies with all required mitigations.”

The challenge for SpaceX is that there really may not be other options for a test site. The most suitable alternative is Cape Canaveral, Florida, where SpaceX launches most of its rockets and expects to operate Starship in the future. But NASA doesn’t want to risk explosive test anomalies near the pads where it launches astronauts. That means if this lawsuit succeeds (or if the FAA isn’t satisfied with SpaceX’s post-mission analyses) SpaceX will be stuck doing the environmental work it arguably should have done years ago, when this vehicle was first conceived.

Federal regulators are typically given fairly wide latitude by the courts, but SpaceX has another card up its sleeve: The US military, intelligence community, and NASA all depend on the company to get into space (and go to the Moon). Those concerns may override legal protections on the environment in Texas, just as similar concerns led the Federal Trade Commission to okay a monopolistic merger of Boeing and Lockheed Martin’s launch businesses in 2006, over Musk’s objections. One attorney told Reuters that Congress could act to override the environmental rules at the Starship site, as it did for some federal oil and gas leases last year.

The argument over Boca Chica’s future touches divisive issues that reach beyond SpaceX, to questions about decarbonization and democracy. Can the US continue to balance a dynamic economy with the rights of landowners and citizens? How do we value life on Earth versus the potential rewards of space exploration? Is the National Environmental Protection Act the right process to find answer these questions?

However these dilemmas are resolved, SpaceX’s Starship is now at the center of the debate over equity in the science fiction future—which is probably right where Musk wants it to be.

🌕🌖🌗

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

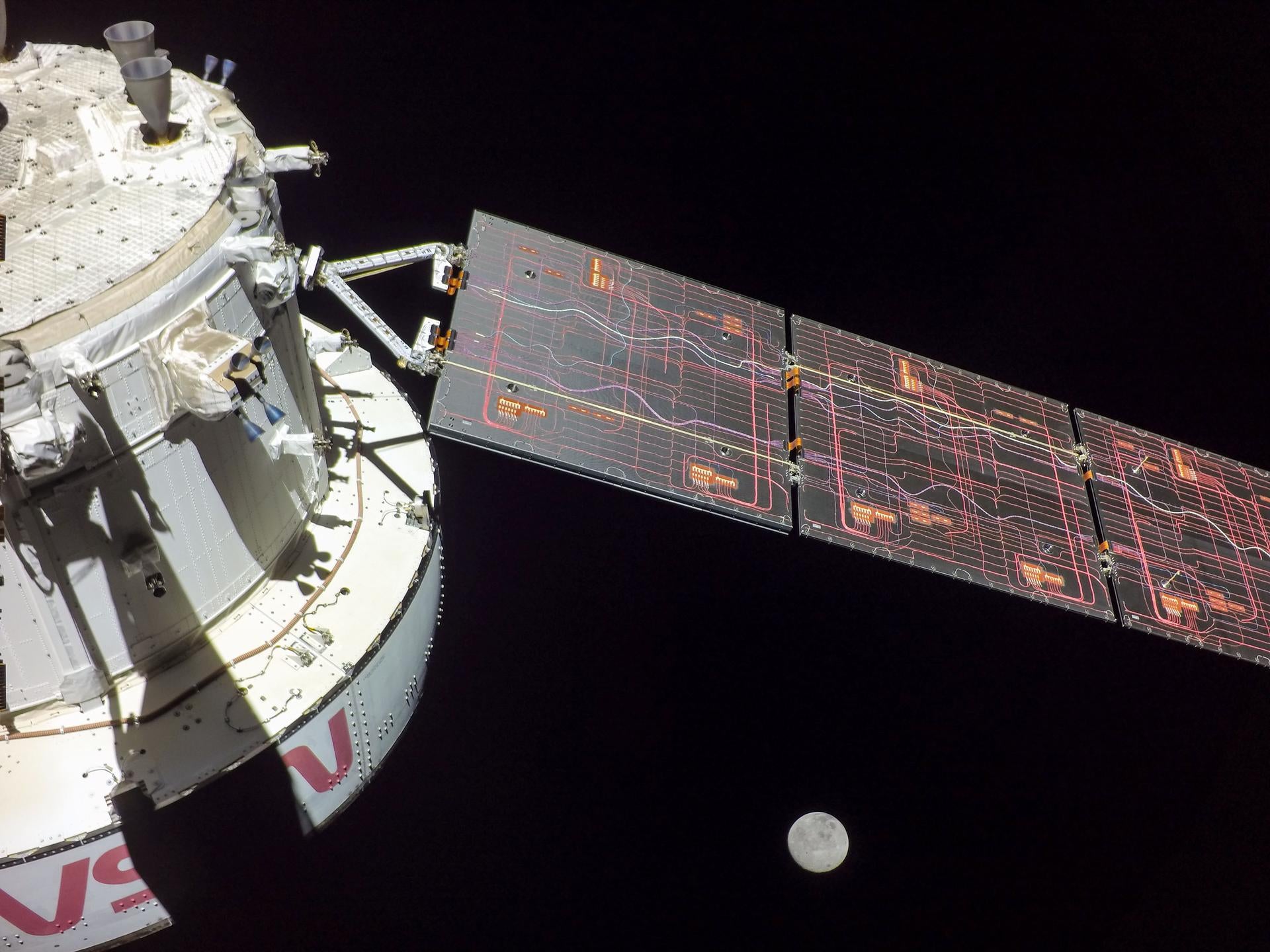

We’ve talked before about the cameras that Redwire made for the Orion spacecraft’s journey around the Moon during the Artemis 1 mission. But I hadn’t realized the modified GoPros that collected some of the coolest images on the mission were communicating via a version of the same wifi protocol you might be using right now.

When SpaceX was building its first rockets, one cost-saving innovation was using modern ethernet cables instead of traditional cabling. Now, we’ve got wifi-enabled spacecraft orbiting the Moon.

SPACE DEBRIS

How much capital does SpaceX need? Elon Musk is, among other things, one of the world’s great fundraisers, a much-needed talent as SpaceX invests billions in ambitious space projects like Starship. Last week, Musk said the company had no plans to raise new capital. But unexpected delays in development could see the company entering the most difficult fundraising environment it has yet encountered.

European satellite firms vie to build Starlink competitor. A consortium including Eutelsat, SES, Hispasat, Airbus, and Thales Alenia has come together to bid on the contract for IRIS², a satellite network funded by the European Union. IRIS² is intended to be Europe’s alternative to Starlink and to China’s forthcoming megaconstellation, but the geopolitics are already tricky: Eutelsat is working through a merger with OneWeb, which is partially owned by the UK government, which European officials have suggested wouldn’t be welcome in a post-Brexit European space project.

Inside the billion-dollar hunt for China’s next weapon. BlackSky, a space data firm, this week revealed the first images of a lighter-than-air vehicle at a remote Chinese military facility. The much-watched complex also hosts what appears to be anti-satellite laser weapons, and highlights the growing business of delivering intel about China’s weapons research to government and private customers alike.

Rocket Lab keeps pushing. Here’s a deep dive into the latest developments at Rocket Lab, the rocket-maker that is out-executing its competitors.

We may not have enough plutonium to get to Uranus. NASA uses the radioactive element to provide a steady power supply during deep space missions, but current production levels of the heavily-regulated radioactive substance might not be sufficient for additional missions.

Last week: The rocky rise of the lunar transportation business.

Last year: How NASA’s Bill Nelson got religion on fixed-price contracts.

This was issue 179 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your bets on the FAA lawsuit, favorite digital protocols you hope to see in space, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].