Space Business: Light the Beam

What is the future of satellite telecommunications?

The shake-out in space business is catching up with satellite operators who rely on large, high-flying satellites to broadcast data to users below.

Suggested Reading

“Overdue” M&A activity is picking up, says Brad Grady, a satellite market analyst at NSR. Look no further than US satellite provider ViaSat’s merger with the European firm Inmarsat last month. The new Viasat is expected to earn around $4.5 billion in annual revenue, making it one of the biggest satellite operators in the world.

Related Content

Meanwhile, Starlink, SpaceX’s space internet network, is reasonably forecast to bring in more than $5 billion in 2023. That signals the challenge ahead for incumbent firms—and more consolidation is coming, with SES, previously the largest satellite operator, now deep in talks with rival Intelsat about a link-up.

“Starlink seems to be on everyone’s mind—it sucks the oxygen out of any room you’re in,” Grady says. But not everything is about Elon Musk.

The end of satellite TV.

It may surprise you that satellite operator revenue, and especially satellite TV revenue, has been falling for years. That’s largely driven by the ability to stream television over terrestrial broadband internet—and it’s forcing companies to look for new business models.

“The economics of space have changed. Revenues on a per unit basis are radically different,” Grady explains, noting that just seven years ago, a satellite operator’s sales team could find one video customer and live off it; today, that operator might need to find hundreds or thousands of data customers to build a business.

That transition has been abetted by widening interest in the industry. “Lots of new folks that are from the app world or terrestrial IT world or telcos are bringing those business models into space,” says Grady. One example is Astranis, the San Francisco firm building low-cost satellites that orbit over one place on the planet, which it sells to single customers interested in regional coverage.

Grady compares that model to software-as-a-service companies, or firms that purchase cellular phone towers and lease their services back to mobile phone operators.

The rise of LEO constellations.

Connecting people with lots and lots of satellites flying near the planet is a business model that was initially defeated by the cost of going to space and the complexity of managing such a network. But once the concept was proven by the pioneering company O3B in 2013, billions of dollars have been invested in networks like SpaceX’s Starlink or Amazon’s Kuiper.

These networks offer faster speeds and broader coverage than those built by firms like SES or ViaSat. But it’s not clear how sustainable they will be, given the cost of such projects—around $10 billion or more–and the crowding in low-earth orbit.

Grady notes that Starlink has yet to win a contract from a company already providing internet access to commercial airplanes, perhaps because of the regulations involved. It’s been easier for large maritime operators like Royal Caribbean to adopt Starlink, but he’s watching how much take-up Starlink finds onboard leisure yachts, fishing boats and merchant ships.

The “multi-orbit” satellite operator.

Promising further consolidation are operators who utilize satellites in different orbits, operating on different frequencies, to provide optimized service to their customers.

We’re not quite there yet. ViaSat wants to be seen as a “multi-orbit” provider, but its strategy is unclear. One hint: It will launch a new satellite for the Air Force in low-earth orbit that relay data between the Earth and geostationary satellites.

But multiple orbits isn’t quite enough. Grady envisions a world where satellite-linked devices act more like modern mobile phones, seamlessly switching between different mobile and wifi networks to provide optimized communication. These kinds of software-defined networks aren’t yet part of the satellite picture, but they’re coming.

The death of the satellite phone.

Multiple companies are working on the technology to link satellites to mobile phones. Apple has already rolled out limited space connectivity for iPhones. Most of these efforts are focused on consumers, but the cost-benefit analysis of plugging cell phones into satellite networks isn’t entirely clear for companies like Verizon or Vodafone. The real target of this tech may be the government—particularly military and intelligence users of expensive satellite phones.

The US Space Force is already talking about how to modernize how it deploys satellite communications. Even limited connectivity to cheap devices might be useful: Instead of find my iPhone, the Pentagon could use “find my soldier.”

🌕🌖🌗

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

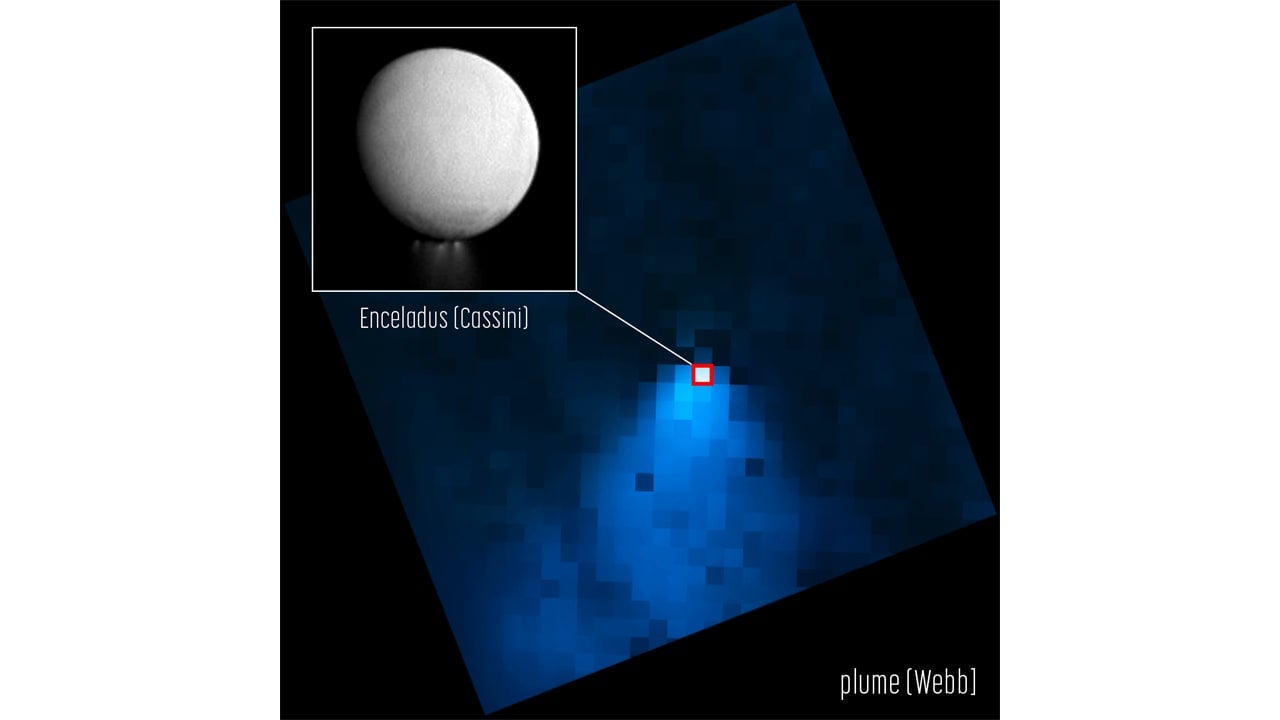

A few weeks ago, the James Webb Space Telescope spotted a massive plume of water emerging from the ice-covered oceans of Enceladus, a moon of Saturn.

Enceladus is seen as an enticing target for exploration because of the water there, and now even more so after scientists detected phosphorus, an element that is key to biological life, in those plumes.

🛰️🛰️🛰️

SPACE DEBRIS

House Republicans plan NASA cuts. Apparently, the debt ceiling deal has not entirely saved the space program: The top Republican appropriator has set spending levels far below those in the agreement, teeing up a potential cuts of nearly 30% for NASA. That would a worst-case scenario—“game over for the space agency’s ambitions this decade,” per the Planetary Foundation’s Casey Dreier.

Planet stumbles in earnings report. The space data company (NYSE: PL) forecast this month that it would earn $23 to $33 million less than expected in its current fiscal year, leading its stock price to sink; however, the company expects revenue to grow between 18% and 23% in the same period.

SpaceX launches the latest space start-ups. The eighth mission in the company’s ride-sharing Transporter series deployed some 72 payloads in orbit on June 12, including an autonomous pharmaceutical lab from Varda Space and an orbital rendezvous demonstrator from Starfish Space.

Is Starship going to delay a lunar landing? Elon Musk’s enormous rocket is NASA’s choice to put humans back on the Moon, but it’s still on the ground. “With the difficulties that SpaceX has had ... you can think about that slipping probably into [2026],” the space agency’s Jim Free said last week, confirming conventional wisdom about the earliest date Americans could return to the Moon. Musk said on June 13 that Starship could fly again in “six to eight weeks.”

Space Industry B.S. Check. The Financial Times ran an insightful piece debunking the more florid claims about the space economy on Wall Street. (I’ve long sought an interview with Adam Jonas, Morgan Stanley’s perpetually bullish analyst, but he won’t bite. Tell him to reach out!) Here’s a similarly good breakdown of the economics of Starship that punctures over-the-top expectations of the vehicle, like a $5 million launch price. This is something that ought to be recognized in the industry: In 2016, Musk predicted SpaceX’s reusable Falcon 9 would cost about $40 million a launch, but today it’s being sold for upwards of $67 million per flight.

Last week: Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos are betting on unproven tech for NASA’s return to the Moon.

Last year: SpaceX made a surprising peace deal to focus on its satellite fight with Amazon.

This was issue 184 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your predictions for the future of geo satellites, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].