At a time when media houses the world over are struggling for eyeballs, a 27-year-old from Indore, Madhya Pradesh, has found a way to get most of the content on his website to go viral.

Vinay Singhal began his entrepreneurial journey with a desire to change India and create awareness about national problems. Instead, seven years on, he has found success via WittyFeed, a website that creates shareable content—the kind that goes “viral.” WittyFeed content spans a range of topics, including lifestyle, entertainment, politics, sports, health & fitness, and celebrities, and includes stories based on news and current affairs, videos, quizzes, and listicles, similar to viral content created by BuzzFeed or UpWorthy.

As of Sept. 13, 2017, Singhal’s creation ranked 41 in India and 407 globally according to Alexa, a US-based service that ranks websites based on popularity, while ScoopWhoop, a BuzzFeed clone in India, is at 453 in India and 5,249 globally.

According to Singhal, his company gets 80 million unique users and 250 million page views a month. In 2016, it earned revenues of around Rs30 crore ($4.5 million) and is profitable, too. On Sept. 12, WittyFeed raised its first round of funding (an undisclosed amount) from a group of angel investors, including Anand Chandrasekaran, former chief product officer at Snapdeal, and Apurva Chamaria, head of corporate marketing at HCL Technologies.

The beginning

Vatsana Technologies, WittyFeed’s parent company, was born in 2011 when Singhal was still an engineering student at SRM University, Chennai. Along with some friends, Singhal launched Badlega Bharat (India will change), an online venture that organised events for social causes. Soon he realised patriotism alone wouldn’t do and Vatsana needed money to stay afloat.

In 2012, Singhal and his current co-founders, brother Praveen (23) and friend Shashank Vaishnav (27), launched a Facebook page called “Amazing Things In The World.” It carried, among other things, baby videos, jokes, nature and wildlife pictures, and inspirational videos. In just six months, the page had over a million followers. The trio then began looking for ways to scale and monetise it. Following a series of iterations and name changes, including stupidstation.com, they launched the WittyFeed website.

Early on, Singhal and his partners realised they were not the only ones in the online content arena, and two of the key areas these companies were struggling to crack were distribution and monetisation.

So, in 2011, they created Viral9. “Influencers can sign up (on Viral9) and have access to all content that WittyFeed has produced and post it whenever they want to their communities,” Singhal said.

Viral9 is run by a 30-member technology team led by Vaishnav and has around 60,000 influencers signed up. Anyone who has at least 100,000 followers on platforms such as Facebook or Twitter can join Viral9 as an influencer. It also takes initiatives to reach out to celebrity influencers to bring them on board.

WittyFeed’s team then tracks the links shared by these influencers in real-time and incentivises them based on the traffic generated. It registers almost 50 influencers a day, Singhal said, not wishing to reveal how much they are paid.

The company itself earns money through advertising (including banner ads on pages, sponsored articles or other paid content such as quizzes for advertisers, and sponsored videos). More clicks and page views brought in by influences mean more revenues.

WittyFeed is heavily dependent on social media platforms, and Facebook is its biggest distribution channel since most of its influences have their largest reader base there.

However, Facebook’s periodic algorithm changes and its mission to crack down on clickbait articles can hit hard. But WittyFeed has always “come back very very strong after each update” by improving the content quality, said Singhal. Such algorithm changes may affect the company in the short-term but works well for the industry in the long-term as it forces websites such as WittyFeed to produce only quality content, he added.

Similarly, with Facebook giving videos more prominence, WittyFeed has had to tweak its strategy and related tech infrastructure.

Yet, three-year-old WittyFeed has over 40,000 stories in various formats in English and Hindi. It briefly experimented with Spanish, too, before lack of resources forced it to go slow. The content is created by an in-house team based on topics suggested by data generated by its own experts.

However, WittyFeed’s clear dependence on influencers throws up unique challenges.

Fly-by-night?

“There is no code of conduct or norm that controls (the industry), and there is no pricing mechanism,” said Vikas Chawla, co-founder of influencer.com, a platform that connects social media influencers with brands. Influencers today have an upper hand and could charge clients heavily, he added.

“Key influencers in the content space need money to do what they need to do and the larger number of followers of you have…the more you charge,” branding strategy expert Harish Bijoor said.

Singhal, however, believes there are no risks involved.

“Because ours is an influencer-driven platform, we believe we will be able to stay relevant always,” he said. “Influencers are always going to be there, in one or the other form. Maybe they are on Facebook today, they’ll be somewhere else tomorrow, but they’re going to be there. That’s the way our society works,” he added.

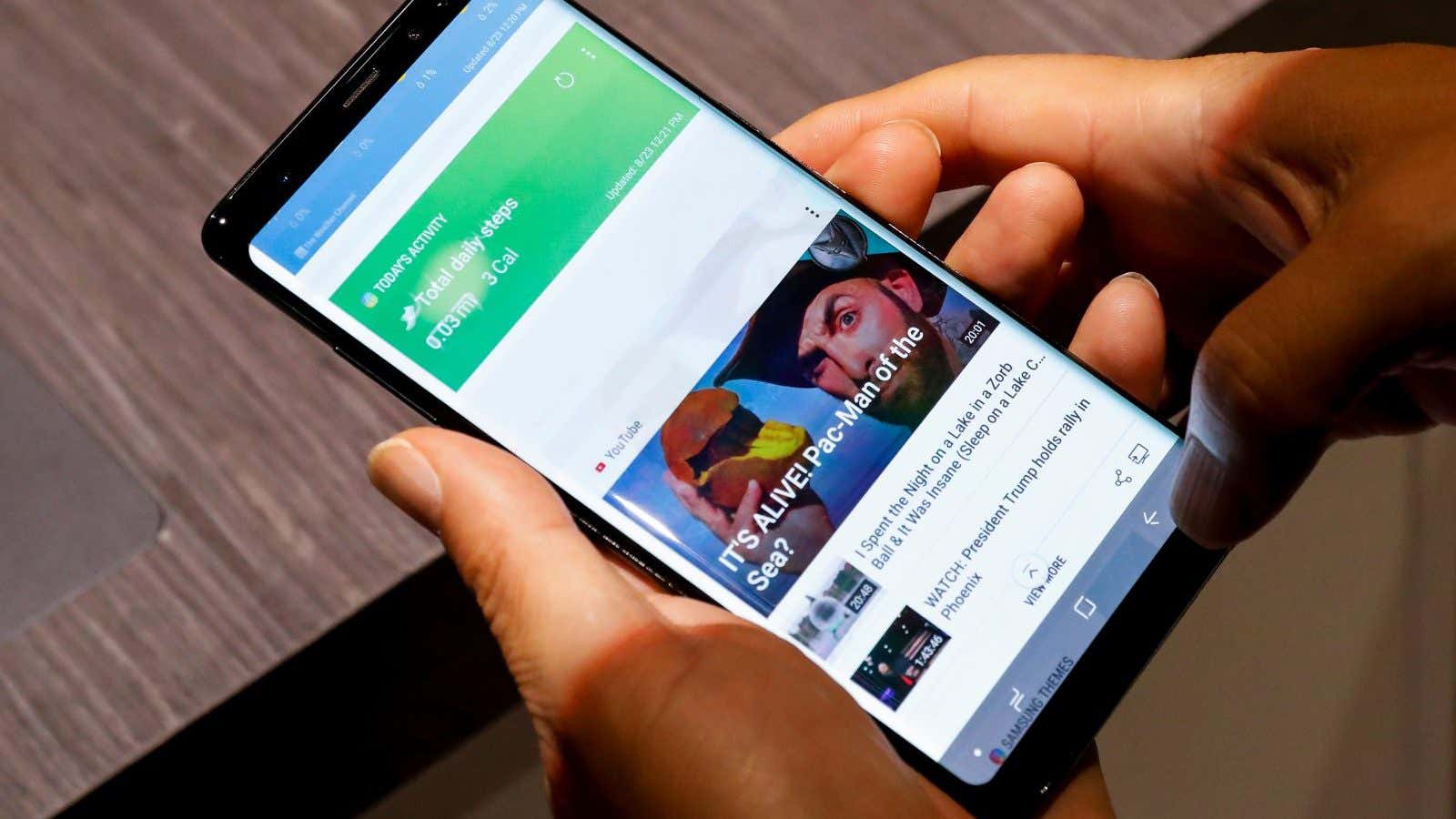

WittyFeed’s strength, he said, is its platform-agnostic content and technology. For instance, it is now gradually adapting to mobile apps. “We will be able to work with any mobile app and convert it into a content app with just one line of code,” Singhal said.

He now plans to invest in technology and geographic expansion.