More Indian women are fighting back against sexual harassment they face over phone calls and text messages, a survey shows.

In an India-based survey by the Swedish phone-identification app Truecaller, nearly 40% of respondents who had faced sexual harassment via calls and SMSes said they’d filed police complaints against it in 2019—a sharp increase from 10% when the company conducted the same survey just one year ago.

Truecaller’s survey, conducted with global market research firm Ipsos, asked detailed questions to over 2,100 women from metro areas across India. All respondents had to be users of the Truecaller app.

The survey, published yesterday (March 07), showed the staggering scale of phone-based harassment of women in India. One in three respondents reported receiving “sexual and inappropriate” calls or SMSes. This is the same figure as when Truecaller conducted the survey last year.

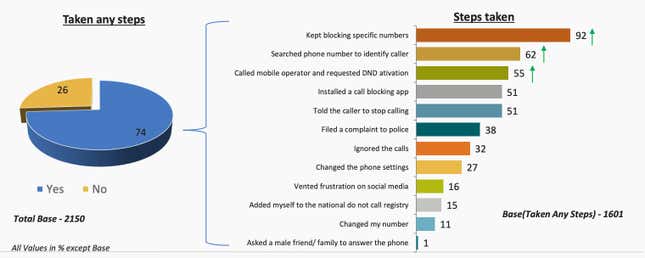

Women’s responses to phone harassment took various forms. While 62% of women reported having “taken measures against” harassment in 2018, 74% did this year. Some of the steps women took this year included blocking numbers, calling mobile operators to request “do not disturb” activation, ignoring calls, and changing one’s number.

Blocking numbers, the most popular step women took, also saw a substantial increase in popularity from last year. While 65% of women who experienced harassment reported blocking offending numbers in 2018, 92% did so in 2019.

Women who faced harassment also reported being more willing to “name and shame” perpetrators on social media—with 7% reporting having done so last year, and 16% this year. In a recent, high-profile instance of this, when television journalist Barkha Dutt experienced a torrent of phone-based harassment, she published screenshots from her perpetrators’ messages on Twitter.

Why this increase?

Some say that this increase in willingness among women to take action may be in part due to the influence of the MeToo movement, which took India by storm last year.

“MeToo had a huge impact across India,” said Gayatri Sethi, the business head of WhiteBalance, a Delhi-based creative studio that Truecaller partnered with on an anti-harassment media campaign called #ItsNotOK. Now, Sethi said, “women can step up and can tell the world about these issues, and understand that they should not just ignore (harassment).”

Truecaller believes that the Indian government’s initiatives to tackle harassment may also be partly responsible for the increased reports to police. “There’s been a major shift in the approachability of the police, and there are several helplines for women to call and report,” Lindsey LaMont, Truecaller’s global brand manager, told Quartz. “I think this has made a big difference.” In October, as #MeToo gripped India, the country’s National Commission for Women launched helplines and a dedicated email address to field harassment complaints.

It is important to note, however, that Truecaller’s survey—of which around 97% of respondents come from the highest socioeconomic classification group in India—cannot at all be considered nationally representative. “One of their criteria for targeting respondents is that they need to be using Truecaller, which is in itself a very limited sample set,” said Ambika Tandon, a policy officer who researches gender and tech issues for the think tank Centre for Internet and Society.

Indian women of lower socioeconomic strata, Tandon suggested, would be more likely to respond to harassment “by going offline or not accessing mobile phones at all, because they don’t have the kinds of support structures that would exist for communities where there is a larger level of access or skill.”

Tandon also cautioned against the survey’s clubbing together of different ways that women are taking action against harassment, for example, by including steps like ignoring calls or blocking numbers next to filing police complaints. This conflation, she said, could risk being seen as similar to instances of law enforcement bias, in which police sometimes tell women to simply block harassers’ numbers—while “not dealing with (the complaint) as rigorously as they would with a physical harassment complaint.”