Porbandar, where Mahatma Gandhi was born into a prominent family in 1869, is a town with a long history of charity and empathy.

As legend has it, Porbandar (also known as Sudamapur) was the birthplace of Sudama, a peasant friend of lord Krishna, one of the most widely revered gods of Hinduism. They both studied at an ashram in Ujjain, Madya Pradesh, where they lived together for 64 days, then returned to their homes. Later, Krishna left his native Mathura, in Uttar Pradesh, to found the city of Dwarka, not too far for Porbandar. When Sudama heard about it, he went to visit his old friend, whom he fund sitting on his regal throne. Krishna stood up and went to hug him as if he was his peer—a gesture that has come to symbolize the value of friendship in Indian mythology.

Their hug is depicted in a sculpture in Porbandar, outside a temple dedicated to the story of their friendship.

It is befitting that Kirti mandir, the home of Gandhi, father of the Indian nation and the man who taught the world the power of nonviolence, would be only a few hundred meters from this temple.

Kirti mandir is a destination for tourists—about 1,500 to 1,700 daily, says Puja Samani, who works as a clerk in the museum and looks after the souvenir shop. The place is a stop along a classic religious tourist route: pilgrims visit Dwarka, Porbandar, and Somnath, a sacred site for the cult of Shiva.

The three-story, 17-room, home where Gandhi grew up is grand. Elegantly decorated with drawings of peacocks and birds and featuring ornate wood fixtures, it is a testament to the wealth he was born to.

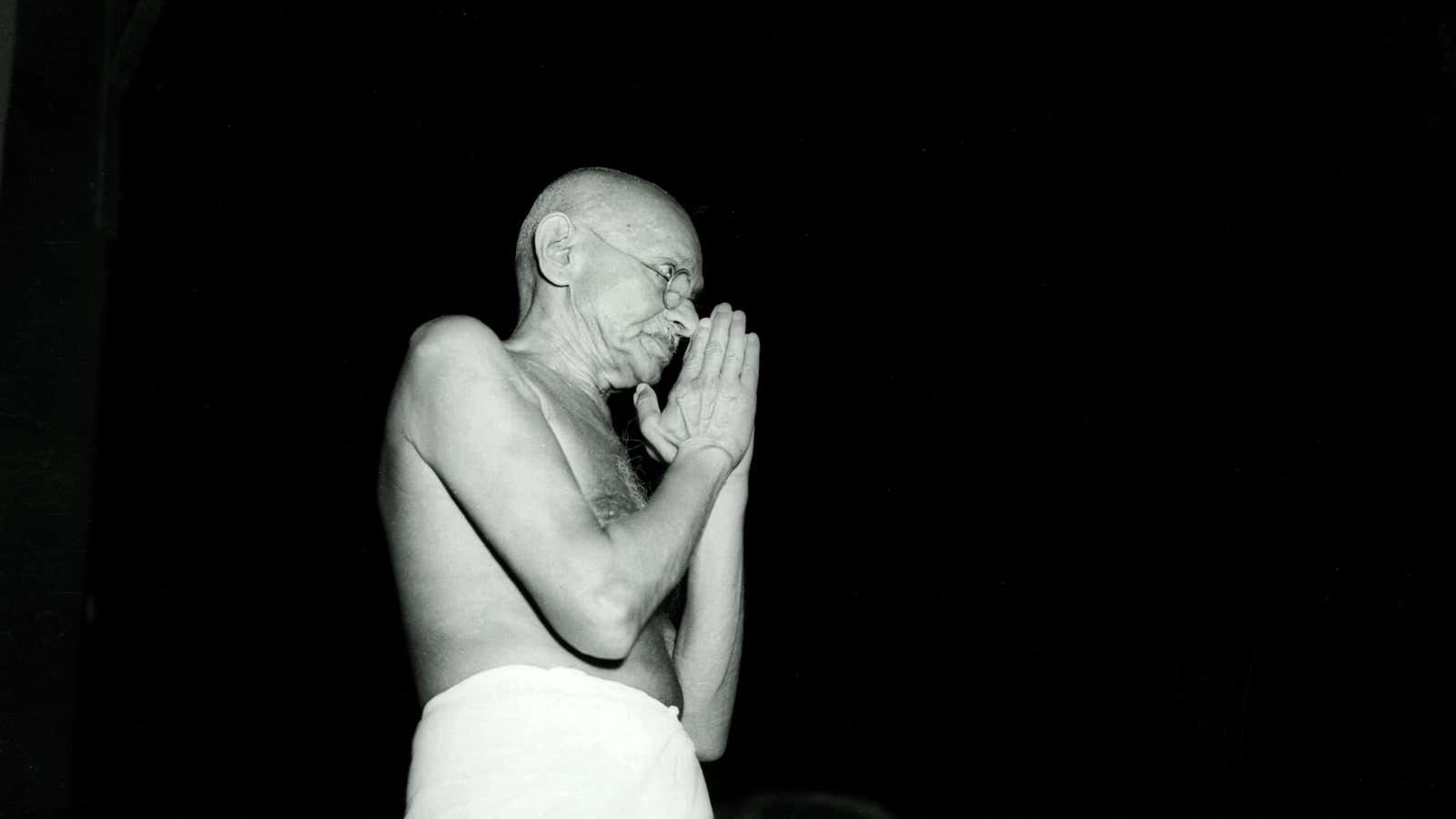

Walking through the home and the adjacent memorial, posters and images covering the walls remind tourists of his life’s journey and the values Gandhi lived by: “Truth, nonviolence, and sacrifice,” says Samani, “these were Gandhiji’s thoughts.”

As India goes through its Lok Sabha election, a visit to Porbandar is loaded with symbolism: The area is a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) stronghold like the rest of Gujarat, which in 2014 voted to assign all of the available seats to prime minister Narendra Modi’s party. This is the same BJP that has driven the most divisive electoral campaign India has ever witnessed, with some of its most prominent members fomenting hatred towards minorities and threatening to enforce ethnicity-based citizenship laws.

Has India—a nation that grew up orphaned, as Gandhi was assassinated in 1948, just months after the country became independent—forgotten the values that made it a model democracy for the world? How do Indians at his birthplace reconcile his message of nonviolence and sacrifice with the passions of sectarian politics?

“We came to show the children where Gandhiji was born and his lifestyle, that he came from so much,” says Ashok Changan, a construction worker from Jamnagar who is visiting Kirti mandir with his family for the third time.

“He said ‘because my country’s people are poor I will not wear more than a loin cloth,” adds his wife, Kailash, a homemaker. She voices what they both think is Gandhi’s most important legacy: combating poverty for all and promoting humility, particularly among the powerful.

They both say they think current Indian leaders are not following Gandhi’s message, with one exception: Modi. Changan pushes back on questions of whether the current government is, together with the broader BJP political message, fomenting violence. “There should be proper policies, and safety,” Changan says, with measures put in place to protect citizenships. He speaks just days after the Sri Lanka church massacres, which Modi has exploited to promote the need of his tough security policies (moves that betray Islamophobic undertones).

“Modiji will fulfill bapu’s [an affectionate nickname for Gandhi, meaning “father”] dream of India,” says Satish Harkani, who keeps the grounds of the home and memorial. He says he puts all his efforts into keeping it neat, as cleanliness was one of Gandhi’s priorities. “People today are not working [Gandhi’s] path, they have completely forgotten what bapu did for this country,” he says.

Harkani singles out Modi within the country’s leadership as one official who is not corrupt—a point that has always been a pillar of the prime minister’ brand. “First of all, we as citizens should start following his messages, only then the politicians will follow that, too,” he says.

“I come here every day,” says Ajit Kumar, a coast guard officer from Haryana posted in Porbandar. “The main reason is that this gentleman has taught the world you can do everything with the power of peace.” For him, too, Modi is a shining example of Gandhian conduct and values, transforming India, showing its power to the world and its own citizens.

Kumar does not seem concerned about maintaining a nonviolent India. He doesn’t deny an increase in violence against Muslims and Dalits in the past few years, and he is somewhat apologetic about it. He believes disadvantaged individuals and communities ought to be given respect—but only if they show respect for power. “First give respect,” he says smiling, as if imparting a motto to a class, “then hope for respect.”

Kumar adds that he isn’t worried about the Indian communities that may oppose the current government. The number is small, “only about 5% to 7%,” he says. “We are not bothered about them.” He says those who support the government will “make it a target” for all to follow the BJP leadership.

“Once they realize we are correct, they will do everything for the country,” he says.

S. K. Dasgupta, a tourist from Kolkata, is reticent to share much information about himself, or his thoughts about the current political system and how it aligns with Gandhi’s views. “The present politicians are not good for the country,” he says in a whisper. “But because of this political situation I can’t say more.”

Samani, the Kirti mandir’s clerk, also has a similar reaction when asked about the current government vis à vis Gandhi’s message.

“What can I say? Nothing,” she says.

Stavan Desai contributed reporting to this article.

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.