When Akbar, at the age of only 13, succeeded to the throne in 1556, the Mughal empire was vast and powerful. When he died, in 1605, he left it three times the size: It was a flourishing empire that encompassed much of the Indian peninsula, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, which gained him the epithet of Akbar the Great.

One of the key factors of his success was tolerance of diversity, and a harmony amongst different rulers. The Mughals were Muslims, a minority in the land they ruled, so it was vital to involve Hindus and other non-Muslims in the running of the state. That’s what Akbar did: Non-Muslims held positions of all levels within the administration—from generals to ministers, from artists to scribes. He didn’t impose an Islamic rule, and he discontinued the levying of the jizia, a tax on non-Muslims, and of any taxes imposed on Hindus traveling to their pilgrimage site.

It was a time in which India shone for its enlightened culture. As author Ira Mukothy noted in a talk about Mughal women in Delhi’s National Museum on Saturday (May 11), while the wars of religion between Protestants and Catholics where burning up Europe, Muslims and Hindus were busy learning about one another, and producing one of the finest testament to the value of intercultural dialogue: The Razmnama.

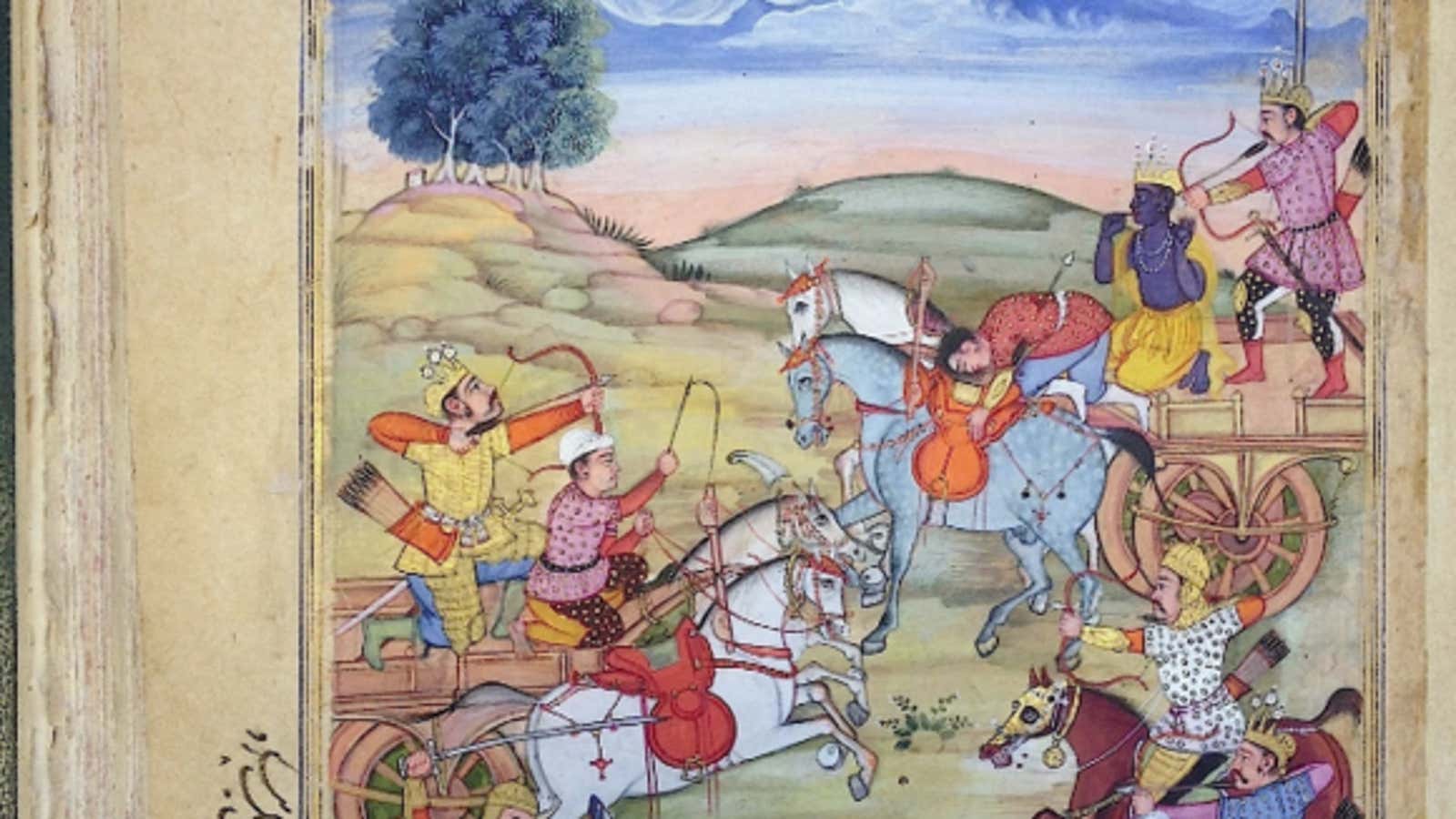

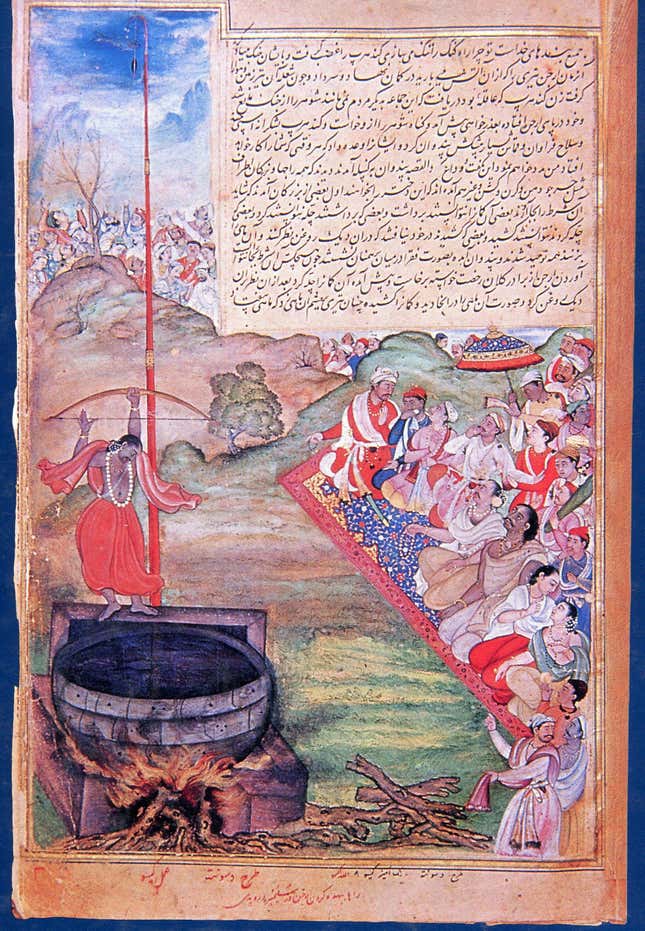

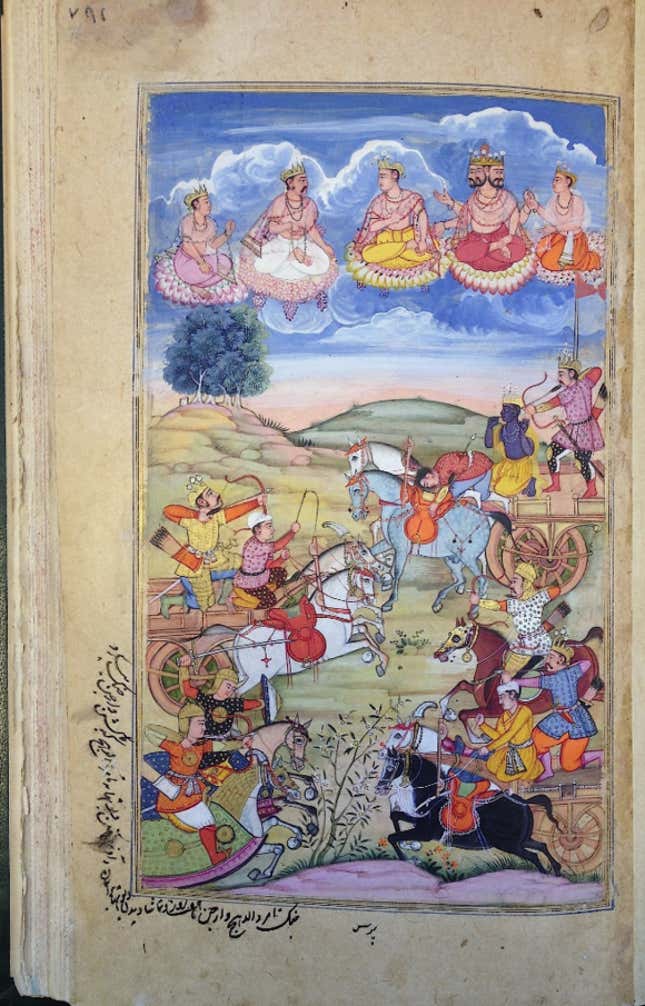

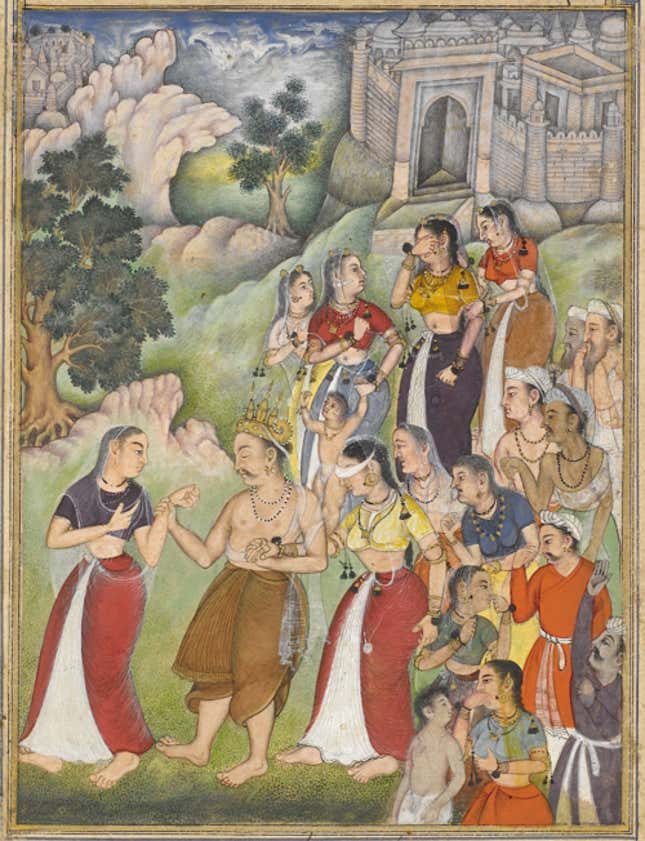

A Persian translation of the Mahabharata, Razmnama means “book of war.” It was completed by the maktab khana, a translation bureau set up by Akbar to translate important Sanskrit texts into Persian. It was Akbar’s intention that the empire be Persian-speaking, and translating the Hindu epics (including the Ramayana, the epic narrating the life of Ram) was a way to encourage sense of belonging and inclusion amongst Hindu subjects, who would see their sacred books as part of the official culture. The bureau was also asked to translate Muslim holy books from Arabic to Persian, so that both Muslims and Hindus could have access to the respective sacred texts in a shared language. As the Razmnama preface explains:

It was desired by the minute-loving reason [of the king] that the Mahabharata, which is replete with most valuable things connected to the religion be translated so that those who display hostility may refrain from doing so, and may seek after the truth…

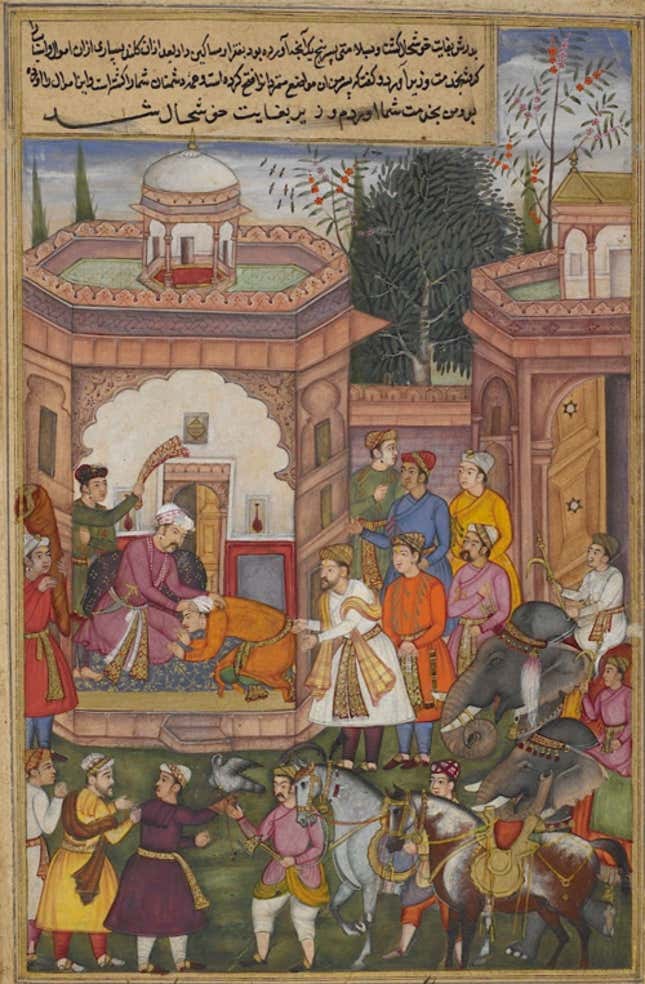

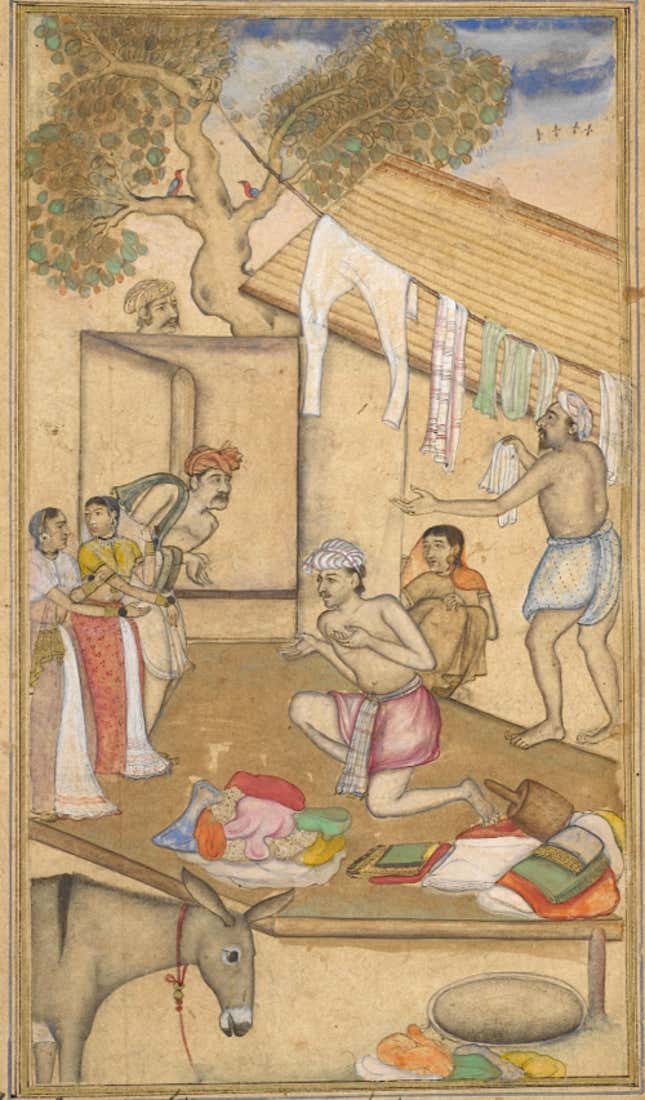

The Mahabharata is a massive 100,000-verse epic—it is the longest known epic poem in the world. Translating it was a massive endeavor that took the maktab khana two full years, between 1584 and 1586. Paintings depicting the project show Muslim and Hindu translators collaborating in the work at the court of Akbar in Fatehpur Sikri: As Yael Rice notes in her paper (pdf, p. 127) analyzing the Razmnama, negotiating the religious nuances of the book required shared work between masters of both languages.

The result, though not a strict translation, was a copiously-illustrated volume, which was intended by Akbar to circulate across the empire: This is why copies of it were handmade and painted, including one, dated 1598-1599, whose pages (though believed to be less elegantly executed than the original) are in several institutions around the world, and upon which much of our contemporary knowledge of the Razmnama is based.

This is not, however, because the original has been lost—quite the contrary. Both the Razmnama and the Persian Ramayana are well-preserved in their full glory, having been housed inside the Jaipur City Palace since 1690. But they have been locked away for decades, out of access for historians and art experts, because of a family feud, Yunus Khimani, who directed the Jaipur City Palace museum from 2010 to 2019, told Quartz.

The two manuscripts, and other Royal properties part of the Maharaja estate have been placed under court seal in the 1980s because of multiple property claims advanced by members of the royal family of Jaipur. The sealed properties are still administered by the court, which will not allow mobile items (that is, anything other than buildings buildings) to be accessed for fear of theft and damage.

And so, a family feud is hiding the precious product of a time when India was a beacon of inter-religious tolerance. For those who would still like to see proof, one of the early copies can be found in Kolkata: The Birla Razmnama, a condensed version of the original, dated 1605—the very year Akbar died.