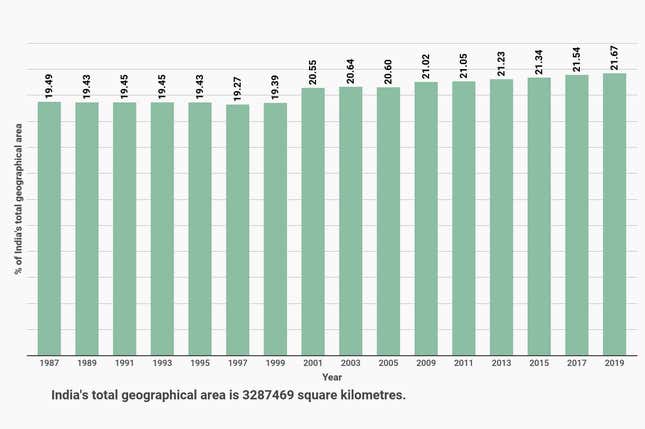

From covering 640,819 square kilometres (19.49%) of India’s total land area in 1987 to covering 712,249 sq km (21.67%) of the country’s geographical area in 2019, India’s forest cover has had a roller coaster journey.

The 32-year-long journey witnessed the rise of a little over 2% of forest cover despite an increase in the population of the country, rapid urbanisation, and tremendous pressure on resources like forests. Perhaps one of the best chroniclers of the change in the forests and their importance has been India’s State of Forests Report (ISFR), which has been released every two years since its first edition in 1987.

However, there have been constant queries raised about India’s forest data, either due to constant revision of official data due to factors like “better interpretation,” or because of questions raised by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

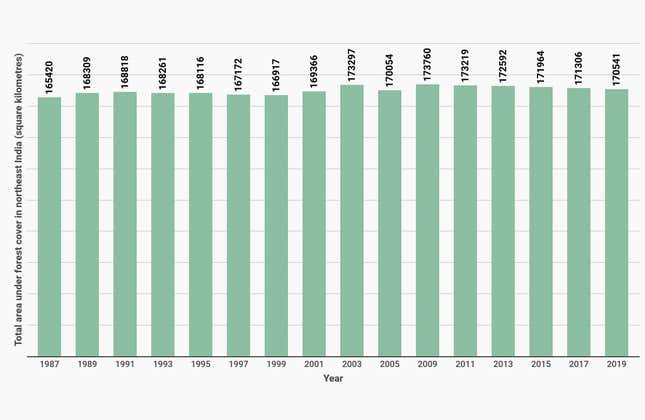

Northeast is a cause for concern

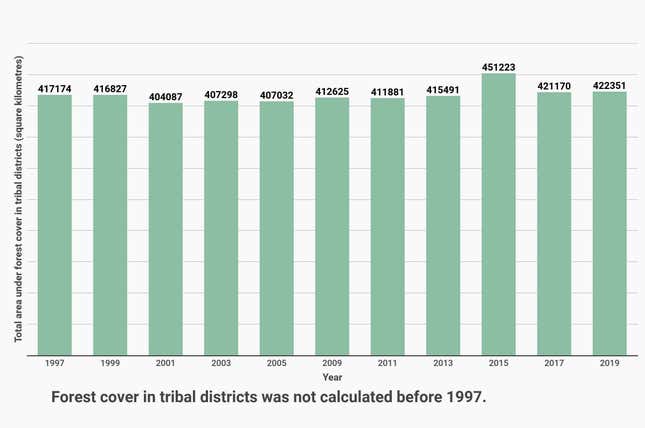

One fact consistently noted by ISFR reports is that there has been a constant pressure on forests in northeastern India and in the tribal districts. According to the report, northeast India includes eight states—Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, and Sikkim.

Though the data in the ISFRs since 1987 may show an actual increase in forests in the region in the last 32 years, nearly every ISFR noted a decrease of forest compared to the previous one. The forest department officials of the government explain the anomaly to better data in the latest ISFRs.

In ISFR 1993, the then environment minister Kamal Nath had said that the data for the northeastern region was a cause for concern. “While efforts at forest conservation and development all over the country have to be pursued vigorously, special emphasis needs to be given to the northeast with regard to policy reform, strategy formulation and programme implementation,” said Nath.

In 1987, when the first ISFR report was released, the then environment minister of the country, ZR Ansari, had said that there are inadequacies in the report but noted that bringing out this first report itself had been a major effort.

Ansari had set the stage at the time, when he had emphasised that the future editions will cover “substantially the same ground but looked at from a different perspective, highlighting a new theme every time on selected topical issues such as social forestry, wasteland development, eucalyptus planting or wildlife.”

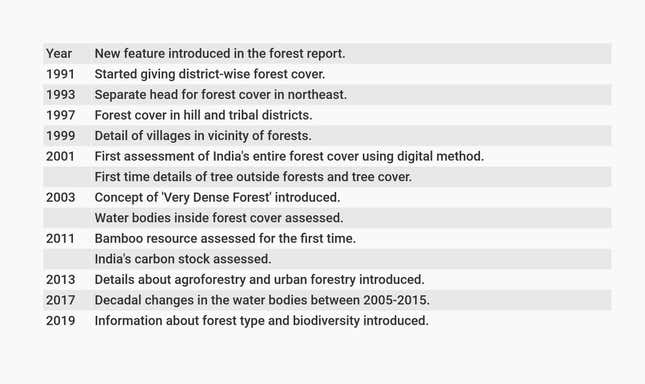

The Forest Survey of India (FSI), which brings out the ISFR report every two years, has stayed true to these words. Every year since then, the FSI has added new themes to these reports, some of which became permanent, while some made way for others.

With the enrichment of data in every new version, the ISFR has travelled quite a distance from being an 87-page book in 1987 to a 604-page book, spread across two volumes, in 2019.

For instance, the first ISFR in 1987 discussed the forest area diverted for non-forestry purposes like mining, river valley projects, highways, etc., which has not been discussed in any subsequent reports. In the reports post the 1987 version, the FSI introduced features like district-wise forest data, forests in the hill and tribal districts, forests in northeast India, forest fire, tree cover, carbon stock, bamboo resource, invasive species and assessment of biodiversity in forests (in the latest 2019 edition).

It has come a long way since 1987 with refinement in data being used to interpret the forest data every few years. But that also resulted in the constant revision of the data in the ISFRs and no two reports being exactly comparable to each other.

Talking about the evolution of the ISFR report, Subhash Ashutosh, director-general of the FSI, said: “There has been a steady and regular upgradation of the ISFR in terms of enrichment, refinement and accuracy.”

“It (the ISFR report) has come a long way. In future, improvements and additions of the future will continue,” said Ashutosh, while recounting his 20-year-long association with the ISFR report. “I joined FSI organisation in 1999 and since then I am associated with the ISFRs. I have seen the evolution of the ISFR for the last 20 years.”

Missing data on forest diversion

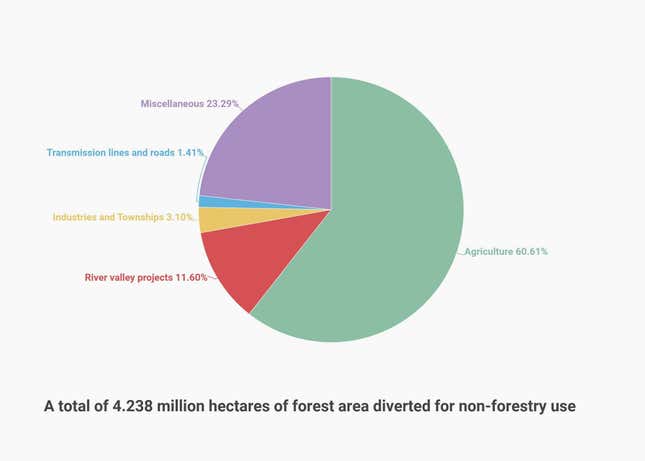

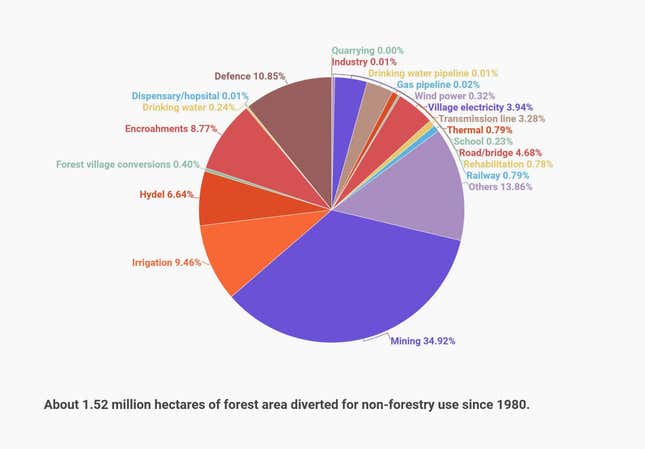

The story of India’s forests can never be complete without the discussion around forest area diverted for non-forestry projects. According to data highlighted by the central government including the ISFR reports, about 4.2 million hectares of land was diverted for developmental projects between 1951-1980. In 1980, the central government enacted the Forest Conservation Act 1980 which made forest diversion difficult. Since then, 1.5 million hectares of forest area has been diverted for such projects.

This means that in the past 70 years, the Indian government has diverted about 57,300 sq km of forest area, which is nearly equivalent to 38 times the size of Delhi.

When asked if the ISFRs in future could look at data regarding the forest areas diverted for non-forestry purposes in a particular state against the increase in the forest area, the FSI’s DG said that is “definitely a possibility” to understand the “trends.”

“There is always room for improvement. For instance, this time we have included information on biodiversity in the forests and also included information regarding people’s dependence on the forest which is very vital for policy planning. There is much more information, which is required by the governments. Next time we could add more to enrich it,” said Ashutosh.

For example, Ashutosh explained that right now they only give forest cover which includes plantations so probably they can look at broadly telling the species in those particular plantations.

“Our work has already started for the next assessment. We just had a meeting on it. We have identified a few possible areas for new data but nothing has been finalised as of now,” he said.

This post first appeared on Mongabay India. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.