On March 1, the Venkatesan family revived an old WhatsApp group that had been lying dormant.

The group had eight people eligible for the Covid-19 vaccine across cities in India, and as many who weren’t. “Did anyone register on Co-WIN yet,” was the first question asked by Ravi Venkatesan, who turned 62 in February. “The site keeps taking you back to the homepage.”

Others hadn’t found the link yet. Those further along the process were not receiving any one-time passwords (OTPs). “I’m logged out now. Do I need another OTP to login?” asked an exasperated Sridhar Venkatesan, Ram’s 58-year-old brother who qualifies for the vaccine because of his co-morbidities.

The offspring took over to help their tech-challenged parents. “I think we should give it a rest for today, it’s too glitchy,” said Anand Sridhar, Sridhar’s 28-year-old son.

The first day of India’s Covid-19 vaccine drive was riddled with tech glitches, some of them that were ironed out in a couple of days, and others that persist 10 days into the programme.

The Sharma family, which lives in Pune, was able to register with the Indian government’s Co-WIN portal in a single try. “It was smooth,” says Ravikant Sharma, a 65-year-old retired government officer. But the real challenge came after he completed the registration for his wife and him.

When Sharma tried to pick a Covid-19 vaccine centre in his district, there were none available with his area code. “I know for a fact that the hospital right across the street is offering the vaccine,” he said. One of the various WhatsApp groups he is a part of, found the solution to that—find the hospital’s name by selecting the city, but not the specific area code.

But where are the slots?

For seven days, Lata Mohan, a resident of Gurugram in Haryana, logged in every day to find and book a vaccine slot on the Co-WIN website. Each time, she would find no slots available for up to a month. Finally, on the eighth day, she called the hospital near her home to find out what the issue was. “They told me to try early in the morning, click on the hospital’s name, and wait for a few seconds,” says Mohan. “Apparently, these hospitals are only releasing limited slots at a time.”

Tech is a major factor in why India’s poor are being left behind the Covid-19 vaccine drive. “A lot of those who are on high posts, who live around the area, and are comfortable with technology are coming,” a doctor at Delhi’s Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital told Scroll.in.

But even those among the affluent chose to completely skip this internet rigmarole. “We walked up to Ganga Ram Hospital and got vaccinated on the first day. We had to wait a bit, but it was still less exhausting than trying to book an appointment online,” said Ravi Oberoi, a 63-year-old chartered accountant in Delhi.

The Indian government has directed hospitals to register those who walk-in without an appointment, but the first 10 days of the vaccine drive left a few hospitals inundated with paperwork and server errors.

But then there were those who had appointments, had all documents in order but were turned away at the vaccine centre.

Challenges beyond the tech

Two members of the Venkatesan family, who stay in New Delhi’s Dwarka, were turned away from a large private hospital for not carrying their doctor’s prescriptions. Both of them were well above the age of 60, and the Indian government has mandated that this age group automatically qualifies for the vaccine, irrespective of whether or not they have co-morbidities.

In Munsiyari in Uttarakhand, Bhairavi Jani’s mother was refused the Covid-19 vaccine. The staff at the small village health centre told her that they could not open a 10-dose vial for one person. While she tried to line up some other people for the vaccine, her husband, with qualifiable co-morbidities was turned away for not having the government’s form signed by the original doctor, who was 14 hours away by road.

And then there is the issue of communication from the hospitals. The Ramaswamy family was turned away from the vaccine centre of a private hospital in Bengaluru on March 11 on account of it being a public holiday. “But then why did they allow us to book an appointment on that day at all?” asked S Ramaswamy.

This is particularly harrowing for senior citizens, who are already nervous about getting the vaccine. Some private hospitals, though, have been doing their best to keep vaccine beneficiaries comfortable. At BLK Super Speciality Hospital in Delhi, for instance, those waiting for their turn to get a shot are offered hot beverages, and there is ample seating space.

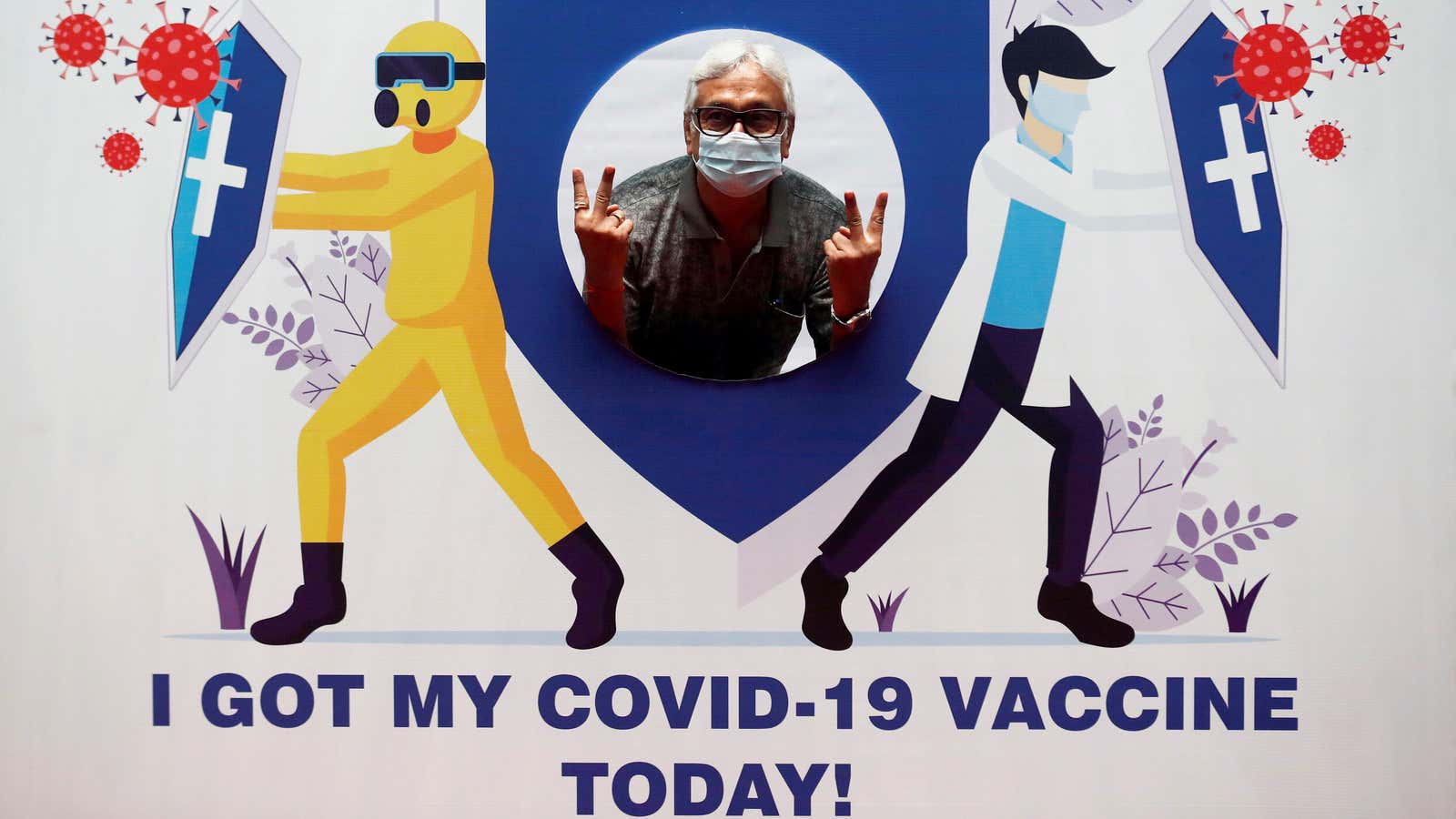

A 62-year-old vaccine beneficiary had to wait for his turn for nearly two hours, but it was bearable, he says. “Some people in the waiting room told me that the (internet) server wasn’t working the previous day so they were asked to come again. There was a backlog, but thankfully, everyone was calm,” he says.