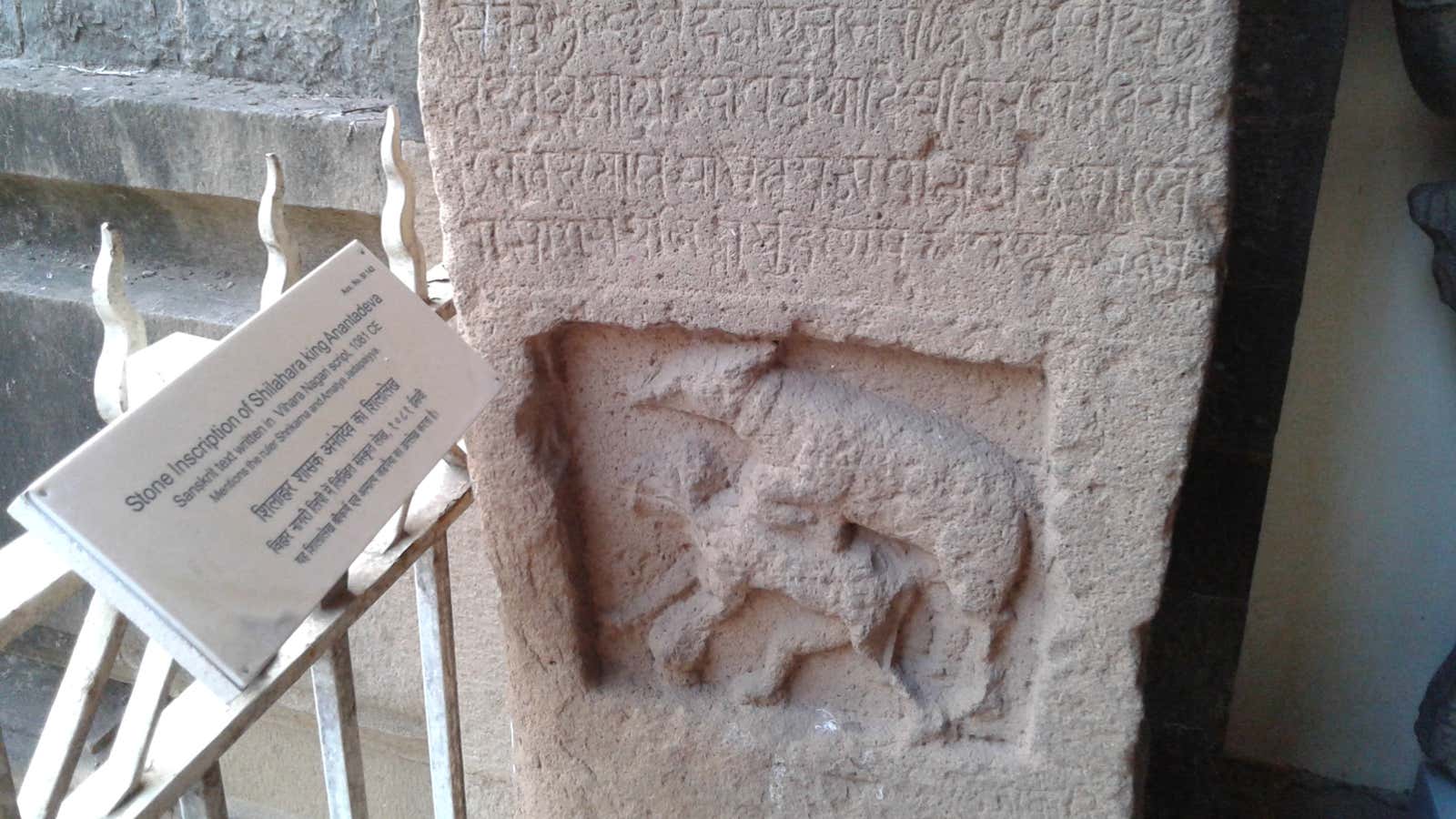

They sit innocuously in an airy gallery in Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji museum—drawing barely a glance. But a closer look at the two engraved stone slabs from the 11th century reveals a rather explicit scene: A donkey with an erect phallus poised over a woman, about to have sex with her.

As it turns out, scores of stone slabs with this configuration of figures lie scattered across Maharashtra and parts of Goa. In Marathi, these stones are called gadhegal, from gadhe, which means donkey, and gal, which could mean either a stone or a curse.

Archaeologists studying medieval Maharashtra have often referred to them as ass-curse stones. But until now, very few scholars have written about them in detail.

New interest

Since 2012, a group of archaeologists in Mumbai and Pune has turned their attention to these stones—and they are discussing what exactly the engravings could mean.

The stones date back to the reign of the Shilahara dynasty from 1012 to 1651, according to archaeologist Kurush Dalal.

“The stones basically served as declarations of land grants given to feudal or Brahmin families, and depicted a curse or punishment that would befall the person who violated the order,” said Dalal, who teaches at Mumbai University’s centre for extra-mural studies.

Over the past three years, Dalal and his team have discovered four new gadhegals in the Konkan region of Maharashtra, as part of their larger excavations of various Shilahara period sites. Three of the stones are in Diveagar, and the fourth is in Deokhol— both in Raigad district.

Dalal has now co-authored two research papers about his findings, and these are due to be published in academic journals this year.

The symbolism

The vertical stone slabs typically feature three panels: The top panel depicts a round sun and crescent moon, the middle contains an inscription in the Devanagari script (or, in some rare cases, Arabic), and the panel at the bottom shows the striking image of the donkey-woman intercourse.

In medieval times, the stones would be placed on the boundaries of a plot bestowed on a family, to serve as a territory marker. The inscription would name the giver and the receiver of the grant, and often explain the symbols on the stone plaque quite directly. The sun and the moon at the top meant that the grant would be valid forever.

“The bottom panel meant that if anyone dared to violate the grant, his mother would—to put it bluntly—be screwed by a donkey,” said Dalal. “But this was not actually meant to be a physical threat.”

In a research paper co-authored by Siddharth Kale and Rajesh Poojari, Dalal describes a prominent theory on the deeper, symbolic meaning of the ass-curse stones, proposed by Maharashtrian archaeologist R.C. Dhere in 1990.

According to Dhere, the woman featured on the stones is symbolic of mother earth, or fertility. The donkey is the vahana (vehicle) of Sitala Devi, the goddess of pestilence and plague, whose cult was very strong during the Shilahara period.

At that time, there was also a widely held belief that if a person’s farms were ploughed by donkeys, it would turn fallow. The donkey and its protruding phallus, then, become symbolic of such ploughing.

“The curse on the stone, then, was that an offender’s land would become barren,” said Dalal. “In an agrarian society, there could be no greater threat.”

In fact, there is a well-known Shivaji legend in Maharashtra that invokes this idea, added Dalal.

In the 1630s, the Adilshahi ruler Rayarao had sacked Pune and is said to have had the land there ploughed by donkeys. Around that time, a young Shivaji came to live in the city with his mother Jijabai, and when they saw the ruins that Pune was in, he had the lands re-ploughed with a golden blade.

“The gold was symbolic of the light of the sun, and after that Pune is said to have flourished again,” said Dalal.

Literal or symbolic?

While Dalal believes there might be some weight in this theory, Mumbai-based archaeologist Harshada Wirkud finds it a bit far-fetched. Wirkud recently researched 34 gadhegals around Maharashtra, including a handful in Mumbai, for her post-graduate diploma, and is now studying the stones further for her PhD in Pune.

“The aim of any pictorial representation is to convey a common message to anyone seeing it,” said Wirkud. The inscriptions on ass-curse stones were written in a language that commoners would easily understand, and Wirkud believes the donkey-woman imagery merely referenced an abusive phrase that is still prevalent in Marathi: “Tujha aai-la gaadhav laagel,” or “may your mother be defiled by a donkey.”

“I don’t think one needs to look at these stones as symbols of mother earth or any goddess,” said Wirkud. “A lot of curse words that we use are still women-centric, and I see this imagery as a similar abusive threat.”

A step ahead

Irrespective of the theory used to interpret gadhegals, Dalal believes it is important that researchers are finally studying them seriously.

“The concept of these stones has been known for a while, but they have not been discussed, because archaeologists and historians were uncomfortable explaining something they considered grotesque,” said Dalal. “But these stones were a significant part of Shilahara history, and thus help us understand the early medieval period.”

The study of the ass-curse stones reveals that such traditions of land grants and sexual threats were popular for nearly 250 years during the Shilahara rule, and the location of the stones reveals the extent of the dynasty’s reign.

In south Mumbai, for instance, there is an 800-year-old gadhegal at Pimpalwadi in Girgaum that is now worshipped as a local deity by devotees visiting a nearby Shiv temple. The inscription on the stone has still not been read and analysed by anyone, although the project is now being taken up by a team of archaeologists led by Abhijit Dandekar from Pune’s Deccan College.

“This stone is the southernmost medieval inscription found in Mumbai, and indicates that there was once a village in the area, with enough land to be granted to feudal families,” said Dalal.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.