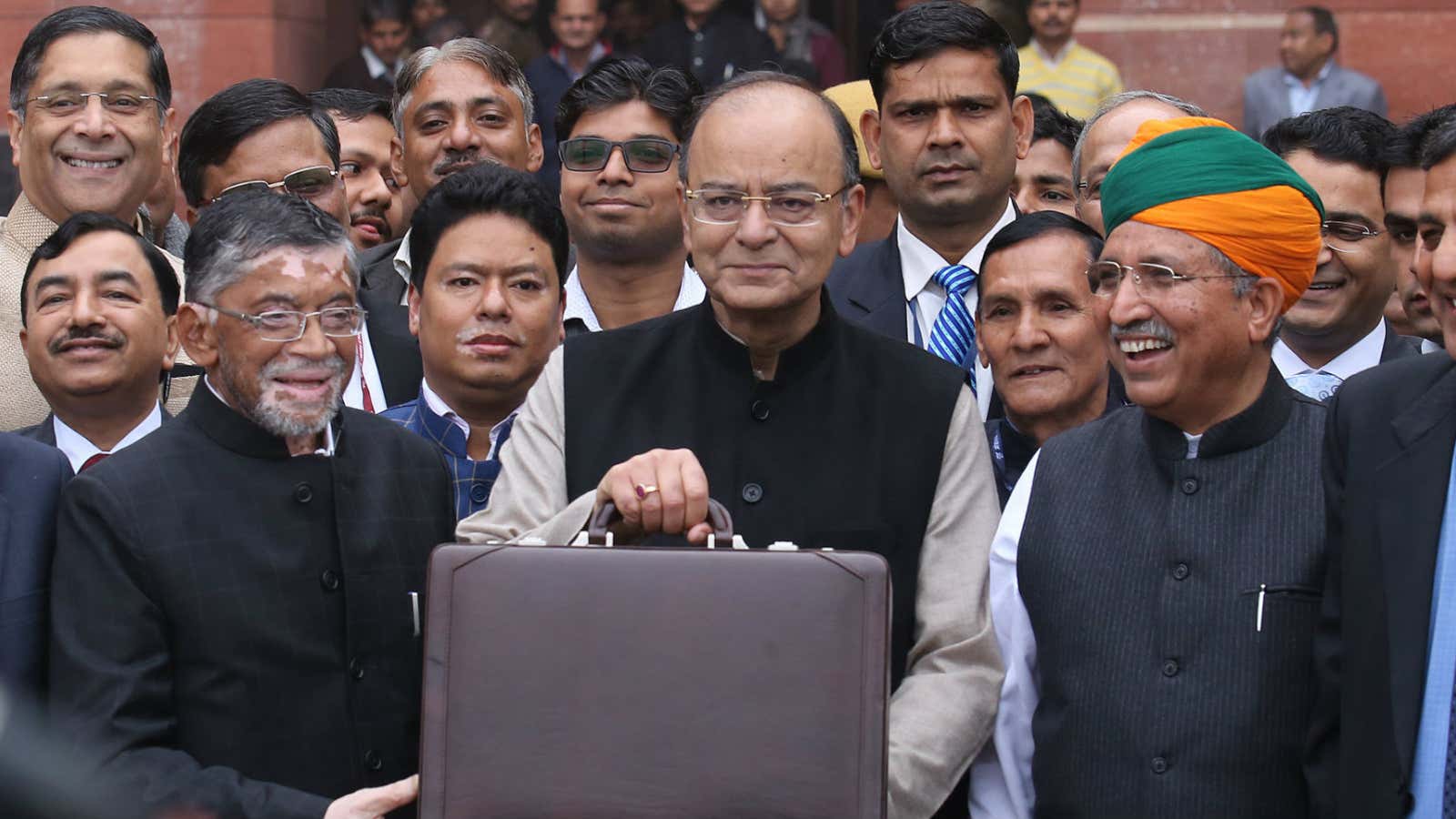

To use an alliteration that his boss would approve of, the budget tabled by India’s finance minister Arun Jaitley today (Feb. 01) was largely about:

Relief: to ordinary Indians who suffered the most due to prime minister Narendra Modi’s surprise demonetisation decision last November.

Resuscitation: provided to the fastest-growing major economy in the world, without upsetting the fiscal math.

Reforms: that’ll help clean up India’s murky political funding ecosystem and push digital transactions throughout the economy.

All of this isn’t entirely original. Three years into its five-year term, the Modi government has typically stuck to a tested formula of spending big on the hinterland and bolstering India’s creaky infrastructure. Last year, too, the thrust of Jaitley’s budget was similar. It was much of the same the year before that.

The results have been decidedly mixed. Although India’s economy has been able to weather global uncertainties—Brexit, US elections, and the rate hike by the US Federal Reserve—better than many of its peers, problems persist. Growth hasn’t quite picked up, industry is suffering, and jobs remain elusive.

The added shock of demonetisation, where 86% of India’s currency (by value) was rendered illegal overnight, slowed down the economy considerably. With little or no cash in hand, consumers drastically cut down on spending, industry stalled, and GDP forecasts were slashed. The worst hit, though, were millions in India’s small towns and villages, cash-dependent small businesses, and the informal sector.

With massive outlays for the farm sector, a raft of measures for rural development, and a record allocation to the country’s main rural employment program, this budget is intended to soothe India’s distressed hinterland.

The politics is unmissable. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party will face a number of key polls this year—in Uttar Pradesh and Punjab shortly, and Gujarat later this year—in the run-up to the general elections in 2019. An irate rural electorate would be a death warrant.

For similar reasons, India’s burgeoning middle-class, still reeling from the cash ban, hasn’t been forgotten either. In his budget speech, Jaitley slashed the income tax rate for the lower rung of taxpayers, those earning between Rs2.5 lakh and Rs5 lakh.

The other big tax cut was for small enterprises with turnover not exceeding Rs50 crore—a significant move considering that small and medium enterprises form 96% of India’s companies.

To further support industry, Jaitley continued with the Modi government’s plan of spending substantially on infrastructure. He has allocated Rs3.96 lakh crore towards this sector, an increase of 13% over last year’s budgetary outlay. In all, the finance minister raised capital expenditure—essentially, money spent on acquiring or maintaining fixed assets—by 25.4%.

Despite the largess, Jaitley remained confident that India’s fiscal math won’t go for a toss.

“My overall approach, while preparing this budget, has been to spend more in rural areas, infrastructure, and poverty alleviation and yet maintain the best standards of fiscal prudence,” the finance minister said. “I have also kept in mind the need to continue with economic reforms, promote higher investments and accelerate growth.”

Such fiscal prudence will do well to support India’s case for a rating upgrade, which has caused some serious friction lately between the government and rating firms such as S&P. Alongside, the move to abolish the Foreign Investment Promotion Board, which cleared foreign direct investment into the country, will help bolster the government’s claim that it is eager for more global businesses to set shop in India.

In the final third of his speech, Jaitley delivered the final R: reform.

“Even 70 years after Independence, the country has not been able to evolve a transparent method of funding political parties which is vital to the system of free and fair elections,” he said. “An effort, therefore, requires to be made to cleanse the system of political funding in India.”

His parliamentary colleagues clapped, even if a tad unenthusiastically, as the finance minister listed out a range of reforms that can potentially transform India’s electoral politics. But as with everything else in India, it all comes down to one I: implementation.

Rural and agriculture

India’s beleaguered agriculture sector, which accounts for nearly 15% of its GDP, received top billing in the government’s agenda for financial year 2017-18, with Jaitley renewing promises to double farmer incomes in five years. The country’s debt-ridden farmers are still reeling from the blow dealt by demonetisation.

Jaitley increased the target of agricultural credit for 2017-18 to Rs10 lakh crore, up from Rs9 lakh crore in the previous financial year. He also announced a 25% hike in funds allocated to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) programme to Rs48,000 crore. MGNREGA is already the world’s largest public works programme, granting workers an assured 100 days of employment in the countryside, but its results haven’t always been desirable.

The budget also outlined the government’s goal for poverty alleviation in the country—about 30% of the Indian population falls below the international poverty line. By 2019, the government plans to bring 10 million households out of poverty and make 50,000 gram panchayats poverty-free.

The government has promised to spend a cumulative Rs1,87,223 crore on the rural and agriculture sectors in 2017-18, up 24% from a year earlier.

Political funding

While the Modi government’s demonetisation move was meant to suck out unaccounted wealth and counterfeit cash from the Indian economy, one area of concern left unaddressed was political funding. It is believed that a good chunk of unaccounted cash is generated through such funding and political parties are often their ultimate beneficiaries, through what is euphemistically known as “unknown source.”

Jaitley’s budget for fiscal 2018 attempts to tackle this anomaly. He announced that parties will now be able to accept a maximum of Rs2,000 from a single “unknown source,” drastically bringing down the limit from Rs20,000. The parties will, however, be allowed to accept more money through e-payments and cheques. The finance minister also proposed to introduce electoral bonds that parties can issue to raise funds.

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a non-profit working towards a cleaner electoral system, recently pointed out that 69% of the over Rs11,367 crore received by India’s six national parties and 51 regional parties between financial years 2005 and 2015 came from “unknown sources.” These numbers were based on the Election Commission of India’s data.

It is unclear, though, how effective this new Rs2,000 cap will be because the parties can always widen their base of “unknown sources.” Nevertheless, the new rules will help in making surreptitious political funding difficult.

Taxes

More than three-fourth of his way into the speech, Jaitley delivered some staggering statistics to highlight tax non-compliance in Asia’s third-largest economy. “India’s tax-to-GDP ratio is very low, and the proportion of direct tax to indirect tax is not optimal from the viewpoint of social justice,” he said.

Demonetisation, Jaitley added, will play an important role in increasing income tax revenues. He said that in the first three quarters of the current fiscal, advance tax (for personal income tax) grew some 34.8%.

To give benefits to the middle class, Jaitley has slashed the tax rate for individuals who earn between Rs2.5 lakh and Rs5 lakh to 5% from the current 10%. The tax savings for individuals could boost consumption as disposable income would spike.

“…Post-demonetisation, there is a legitimate expectation of this class of people to reduce their burden of taxation. Also an argument is made that if a nominal rate of taxation is kept for lower slab, many more people will prefer to come within the tax net,” Jaitley said. For all the other tax slabs, the budget has proposed a uniform benefit of Rs12,500 per person.

High-net worth individuals, though, will be taxed higher. Jaitley has proposed a surcharge of 10% for those with an annual income between Rs50 lakh and Rs1 crore. Already there’s a 15% surcharge levied on individuals with an annual income of more than Rs1 crore, which will remain in place. This will give the government an additional Rs2,700 crore in revenue.

Apart from individuals, small companies also have a reason to cheer. Income tax for companies with an annual turnover of Rs50 crore was slashed to 25% from the current rate of 30%. Some 96% of the companies which file returns will benefit because of this tax-rate cut. “This will make our MSME sector more competitive as compared to large companies,” Jaitley said. Small firms were the first to bear the brunt of the currency ban, as most of them deal in cash for everyday operations.

The budget contained no announcements about corporate and capital gains taxes, something which stock investors were monitoring.

“No change in capital gains tax regime for listed stocks and clarification on non-applicability of indirect transfer rules to foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) and alternative investment funds (AIFs) will be a big relief to the investors and could trigger an immediate rally on the stock markets,” Girish Vanvari, head of tax at KPMG India, said in an emailed statement.

Meanwhile, Jaitley said the government might make some changes to laws or even pass a new law to confiscate assets of offenders—including economic—who have fled the country to escape legal consequences.

Digital play

Digitisation has been the calling card of the Modi government ever since it came to power in 2014. It has sought to harness initiatives in this regard across several areas, such as monetary transactions, launching and running businesses, railways, education, and governance. Demonetisation provided a booster shot as the government looked to offer e-payments as an alternative for people to deal with the cash crunch.

Taking these efforts further, Jaitley announced that no transaction above the value of Rs3 lakh would be allowed in cash.

“Promotion of a digital economy is an integral part of government’s strategy to clean the system and weed out corruption and black money…India is now on the cusp of a massive digital revolution,” he said.

The government is targeting 25 billion transactions during the 2018 fiscal year through new and old facilities, such as Aadhar Pay, the Unified Payment Interface, Immediate Payment Service, and debit cards. The finance minister said that the country’s public and private lenders plan to introduce 10 lakh new point of sale (PoS) terminals by March 2017 and added, “Banks will be encouraged to introduce 20 lakh Aadhar-based PoS by September 2017.”

The Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM), a mobile app launched by the government in December, facilitates e-payments through bank accounts and has been used by 125 lakh people so far, Jaitley said. To increase its adoption, two new schemes will be launched, including a referral bonus for individuals and a cashback scheme for merchants.

The government will also launch Aadhar Pay, which will allow transactions using Aadhaar numbers and biometrics. “This will be specifically beneficial for those who do not have debit cards, mobile wallets and mobile phones,” Jaitley said.

The government has allocated Rs10,000 crore for the BharatNet Project that involves laying optical fibre in 1.5 lakh village panchayats. This will enable the setting up of wi-fi hotspots and provide access to inexpensive digital services. The government will also launch a “DigiGaon” (digital village) initiative to provide telemedicine, education, and skills through digital technology to rural households.

Infrastructure

In all, India’s latest budget is a bonanza for the country’s struggling infrastructure sector. The government has allotted a record Rs3.96 lakh crore for it, almost 80% more than what it received last year. However, this also includes allocation for the railway sector, since India has done away with the railway budget.

“We are now in a position to synergise the investments in railways, roads, waterways, and civil aviation,” Jaitley said. “This magnitude of investment will spur a huge amount of economic activity across the country and create more job opportunities.”

Railways: India has the world’s fourth-largest railway network. The 162-year-old Indian Railways is also the country’s largest employer, providing jobs to as many as 1.54 million people. The railways also has a chequered history in terms of passenger safety, though. Over the last two months alone, India saw three train accidents that killed over 100 people.

The finance minister has now proposed a slew of measures to augment its existing infrastructure.

To begin with, it will create a Rashtriya Rail Samraksha Kosh that will build up a corpus of Rs1 lakh crore over the next five years to be used for safety works. The government will also spend Rs1.31 lakh crore for capital and development expenditure in 2017-18. It plans to add 3,500 kilometres of railways lines in that period, 700 kilometres more than in 2016-17.

In line with plans to go green, 7,000 railway stations will begin to use solar power in the medium term; work is already underway at 300 of them. By 2019, all train coaches will have bio toilets. To ward off competition in freight from the private sector, Indian Railways will begin end-to-end integrated transport solutions for some commodities through partnership with 18 logistics players.

Roads: Over the next year, the Modi government will spend 11% more on building India’s highways. It will add 2,000 kilometres of coastal connectivity roads for better access to ports. Jaitley promised to spend Rs27,000 crore on rural roads through the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana this year.

Housing: When Modi addressed the nation on New Year’s eve, he reiterated his government’s focus on affordable housing. Jaitley’s budget now proposes to construct 10 million homes for the homeless by 2019. The finance minister has also increased the budget for the PM’s Awas Yojana, launched in 2015 to achieve the government’s mission of “Housing for All by 2022,” to Rs23,000 crore from last fiscal’s Rs15,000 crore. The government has also granted infrastructure status to affordable housing, extending tax benefits and lowering the borrowing cost.

Manu Balachandran, Suneera Tandon, Itika Sharma Punit, Maria Thomas, Diksha Madhok, and Harish C Menon contributed to this article.