Christopher Nolan was 7 years old when he first saw 2001: A Space Odyssey, and look where he is now: one of the most famous and important filmmakers in the world. So maybe you shouldn’t laugh at his idea that all young children would benefit from watching Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi epic.

Nolan, making the press rounds promoting his latest film, Dunkirk, told the Los Angeles Times yesterday (Jan. 4) that he showed 2001 to his kids when they were around 3 and 4 years old—an age most would consider too young to understand or appreciate the enigmatic film:

I think they’re able to absorb it on the most important level at a young age. That’s what happened to me. I saw it when I was 7 years old, and that’s the level I think it works the best—pure cinematic spectacle. I was extremely baffled by it, but excited by it.

When people talk about the age of people watching a film, part of what they’re asking is, “How does a 7-year-old parse the content?” And if you look at 2001 and you think about it, you can’t parse it anyway as an adult. The experience is the thing.

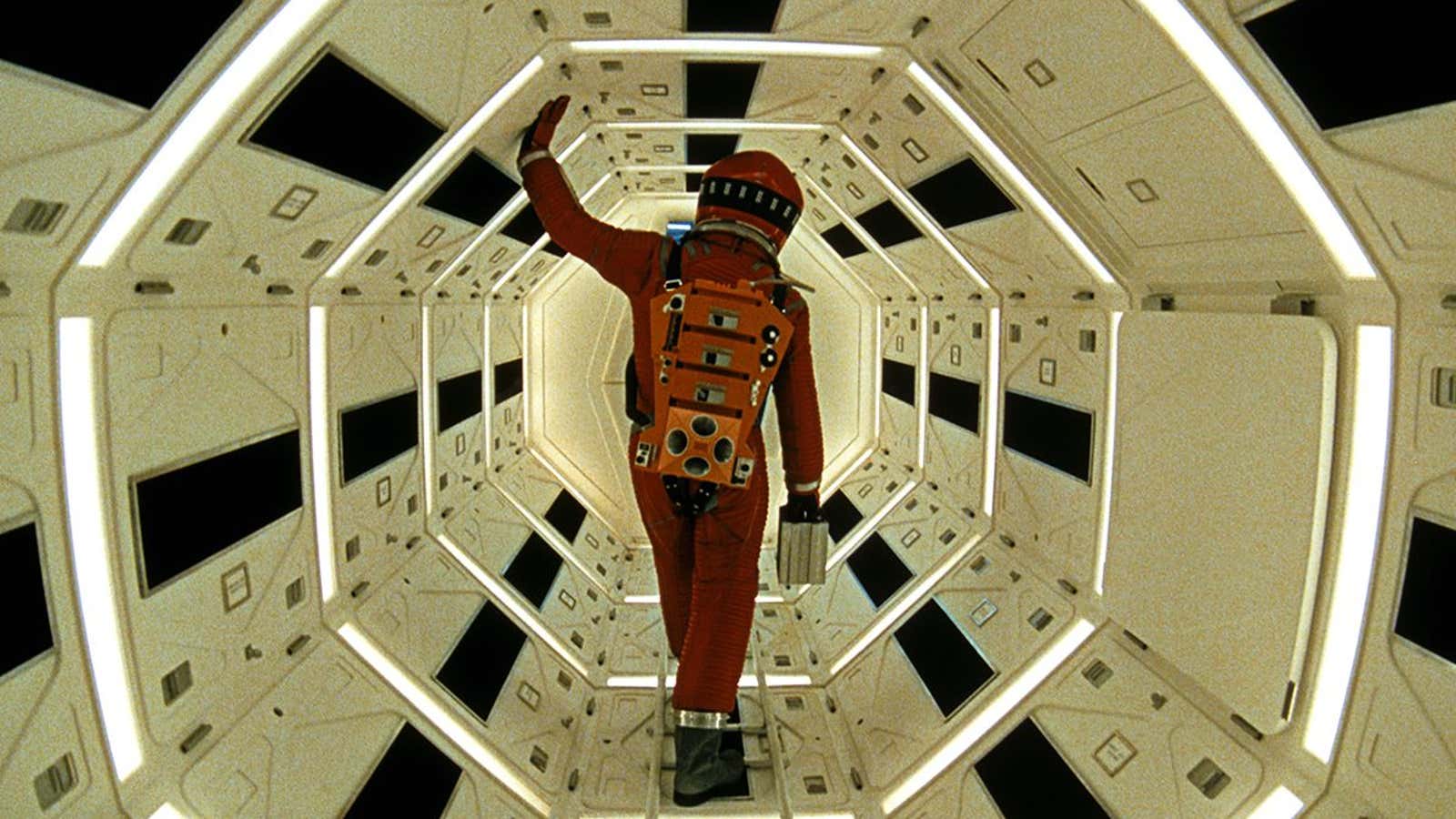

Released in 1968, the plot of 2001 mostly defies description. It’s ”about” a mysterious spacecraft bound for Jupiter. Only the ship’s possibly evil artificial intelligence, HAL, knows the mission’s true purpose: to investigate a radio signal beamed toward Jupiter from the Earth’s moon by an incomprehensible monolith. These monoliths, whatever they are, have been around a lot longer than humans, observing and arguably orchestrating events for a very long time.

Long, slow, and at times maddeningly perplexing, 2001 is not a film most parents would have their children watch. It provokes elaborate philosophical interpretations, while simultaneously resisting them completely. That you can’t understand it makes you want to understand it all the more.

But a child, Nolan says, is not faced with that paradox. There’s an unsuspecting innocence—almost a gullibility—in the way children watch films, and it allows them to be immersed in the world of a movie without having to think too much about what it means. A child just watches and feels things. A child experiences.

“The fact that it’s challenging cinema in an intellectual sense doesn’t bother you when you’re a kid,” the filmmaker told Entertainment Weekly in 2013. “You just appreciate the feeling of the movie.”

Nolan first rose to prominence making films that were far more cerebral than experiential: Inception, Memento, and The Prestige are the handiworks of an artist exercising the power of the mind, sometimes at the expense of emotion. But lately, his films have moved more toward the visceral—less “thinkers” and more “feelers,” hulking tidal waves of movies that envelop you in experience.

His two latest, Interstellar (clearly influenced by 2001) and Dunkirk are both raw, immersive films. Dunkirk intentionally chooses not to flesh out any of its characters or tell their backstories. Viewers are simply thrust into the chaotic Dunkirk evacuation during World War II. What Tom Hardy’s character’s childhood was like isn’t important. What’s important is that the Luftwaffe is trying to shoot him out of the sky. There’s no plot to dissect. It’s immediate, primal, instinctive.

It does include Nolan’s signature clockwork filmmaking approach (the film covers three separate timelines that slowly converge), but he sets it up in a way where the viewer is not even meant to think about it. Dunkirk represents Nolan’s attempt to combine the puzzle-box approach of his earlier films with the more experiential sensation of, say, a young child going to space.

Perhaps subconsciously, Nolan made Dunkirk in part to replicate his experience as a small child watching 2001. Of course a 7-year-old doesn’t understand it—that’s the whole point, Nolan might say. They’re not supposed to.