Emoji have been called the lingua franca of the digital age. It doesn’t matter how old you are or what language you speak, chances are at some point you’ve used smiley faces, hearts, or any of the more than 2,500 expressive digital symbols available on various platforms.

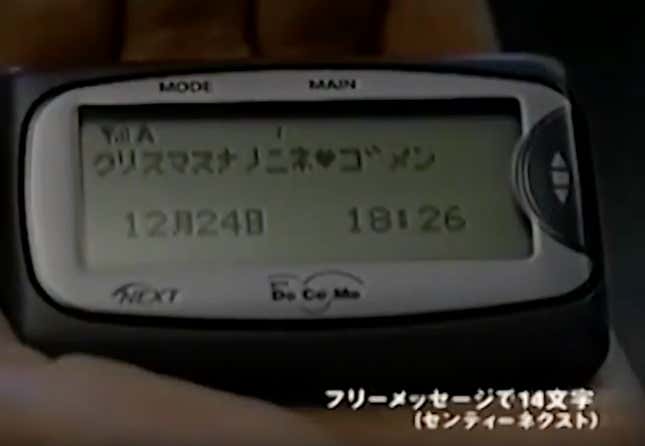

Conceived nearly 20 years ago by artist Shigetaka Kurita, the original emoji were intended for long-winded users of the “Pocket Bell,” a pager made by Japanese telecommunications company DoCoMo. The Pocket Bell’s digital keyboard included with two pictograms: a heart and a telephone. Seeing the popularity of the heart pictogram, DoCoMo tasked a 26-year-old employee—Kurita—to come up with more symbols that might attract customers to its new mobile internet service, “iMode.”

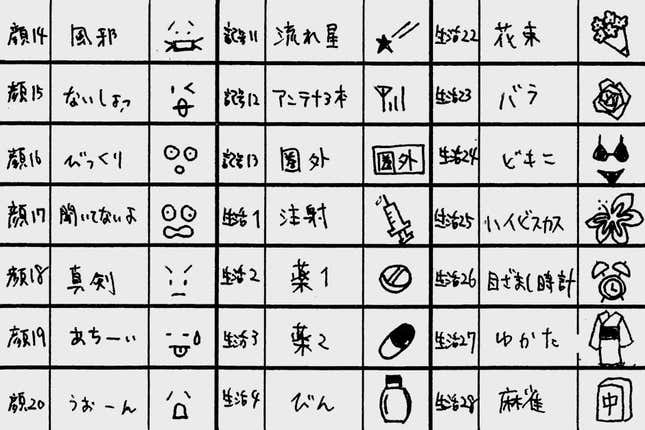

Messages sent through beepers and early cellphones via iMode were limited to 250 characters; the emoji would say the rest. Kurita worked in the sales department and saw first hand how customers loved Pocket Bell’s hearts. Despite or perhaps because he was forced to work within a tight deadline and strict technical parameters, Kurita’s 176 symbols were so captivating that they’re now in the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art.

“We thought emoji would be a quick and easy way for them to communicate,” Kurita told the Guardian in 2016. “Plus, using only words in such a short message could lead to misunderstanding…. It’s difficult to express yourself properly in so few characters.”

Despite his work’s incredible influence, Kurita, now employed by a gaming company in Japan, isn’t well-known. “He’s just a regular guy who was part of something amazing when he was younger. He is extremely surprised by the explosion of emoji” write graphic designers Jesse Reed and Hamish Smyth, who are raising funds to print Emoji, a book celebrating Kurita’s pixel-perfect set.

Reed and Hamish, co-founders of New York-based publishing outlet Standards Manual, are renowned for repackaging logo manuals into handsome coffee table books. The duo tracked down Kurita and his former DoCoMo teammates in Tokyo. They learned that the original emoji were influenced by a range of Japanese pictograms, such as signage in train stations and anime dingbats from manga comics. Kurita also told the Guardian that he was inspired by symbols he saw used in weather reports to quickly convey an idea or emotion without words.

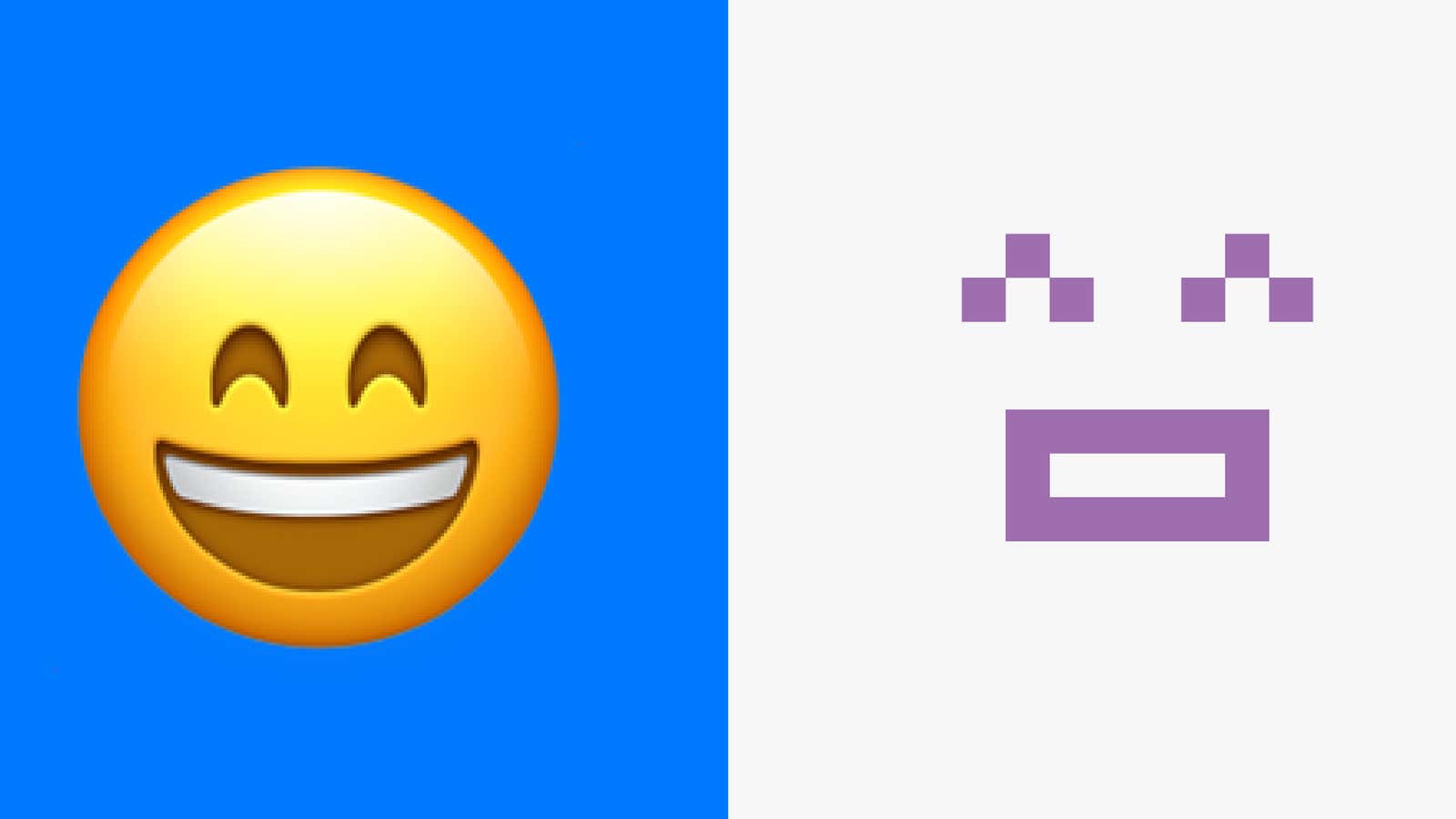

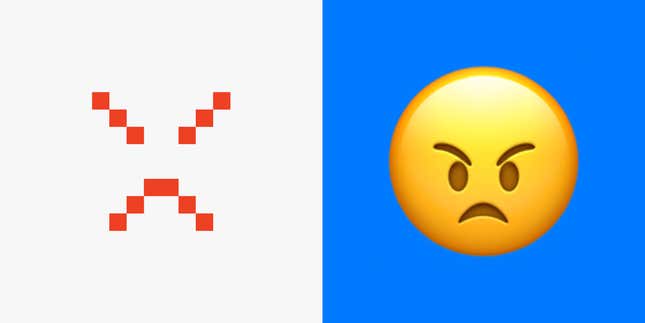

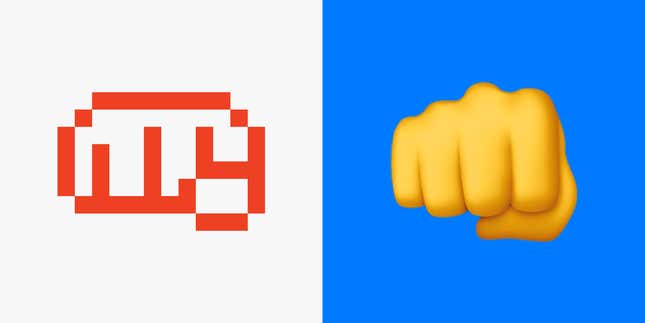

In the book, seeing each original pixel graphic next to its contemporary emoji equivalent underscores Kurita’s genius. “It’s more difficult to convey an idea in the most simple way possible, and that’s what Kurita was able to achieve,” Reed and Smyth write in an email. “Certainly, today’s emoji are more nuanced and detailed, to the point that we have dozens for subtle differences in, say, facial expressions. [But] there is something so pure and refined about the original set that we were drawn to as designers.

“The original emoji had a very limited canvas of 12 by 12 pixels to work with—144 pixels total. That constraint was due to screen resolution, but also data transfer rates of the era,” they explain. “Today, an emoji might be designed with vector tools [drawing programs like Adobe Illustrator], effectively an unlimited resolution, and end up in an emoji measuring at least 256 by 256 pixels. That’s over 65,000 more pixels to work with.”

Reflecting on emoji’s cultural resonance, Reed and Smyth underscore how the tiny, modern-day glyphs have changed the way we communicate. “It’s an evolution to written language that welds the very first primitive symbol-based communication humans used, with digital text communication,” they explain. “In that regard, if you erase The Emoji Movie from your memory, emoji is really cool.” 😎