This article contains spoilers about the May 13 episode of HBO’s Westworld.

In the comedy series Silicon Valley, HBO already has one TV show that roasts the American tech industry. Now, it can boast another, more philosophical one that does the same: Westworld.

From its first episode, implicit in the robot-Western drama’s exploration of artificial intelligence was a probing of big tech’s attempts to replicate human life with machines. (Should we create robots? What happens when we do?) But in its second season, Westworld has become much more explicit in ridiculing Silicon Valley—for its privacy intrusions, and now for the ineffectual hubris of people and companies trying to cure death.

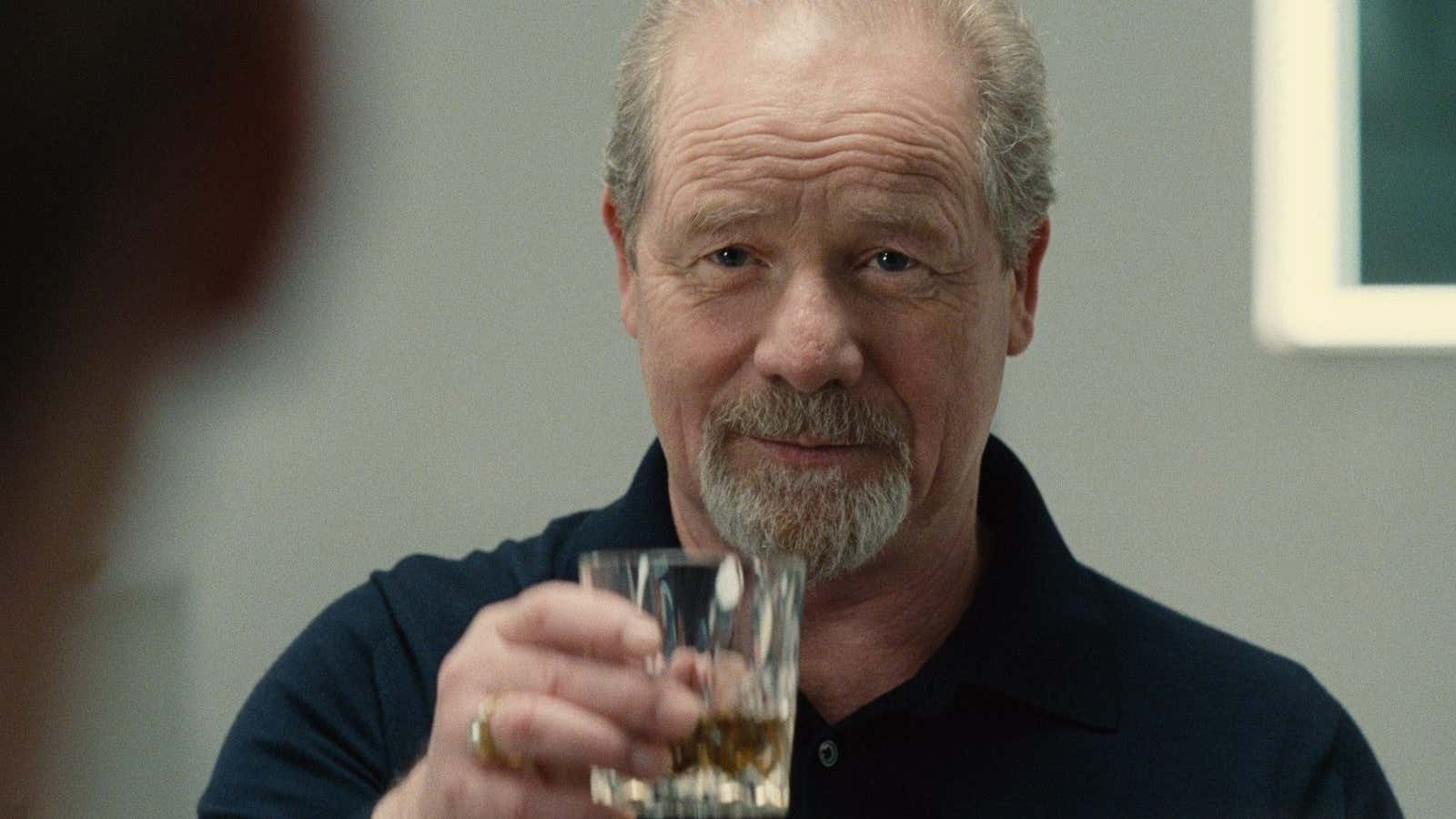

Last night’s (May 13) episode, “The Riddle of the Sphinx,” flashed back to the time when William (also known as “The Man in Black”) tried, unsuccessfully, to make his rich father-in-law (and namesake of the company that owns the Westworld park), James Delos, immortal. After dying of an unspecified disease, Delos’ consciousness was uploaded into a robot clone of his body. Over a period of many years, William and his team observed robot James, building new versions to iron out kinks in his coding. All robot James wanted was to be freed to smoke his cigars and sail his boat as he did as a real human. But after awhile, each iteration of James would begin to degrade, his mind unable to come to terms with life after death—a phenomenon William’s scientists dubbed the “cognitive plateau.”

William eventually accepts that human beings can’t—and probably shouldn’t (especially if they are wildly powerful, immoral tech entrepreneurs)—beat death.

“People aren’t meant to live forever,” William tells a malfunctioning robot James, during his last visit with him. “Take you for example: ruthless philanderer with no ethics in your business or family dealings, a veritable shit head. In truth, everyone prefers the memory of you to the man himself. The world is better off without you.”

As James grows more hostile, his uploaded mind completely collapses, leaving a stuttering, twitching, violent husk of the original man. William decides to leave him in that state, telling his underling not to terminate the experiment as they had done so many times before. Ironically, that decision gives James a version of the immortality he so desperately sought. The only way to achieve life after death, apparently, is to strip yourself of humanity.

That’s a lesson the makers of Westworld apparently hope we learn before its too late. America’s tech industry is on a quest to cheat death: from Alphabet’s Calico, to billionaires like Peter Thiel, to the innumeral Silicon Valley startups looking to prevent aging. Of course, actually doing so would be prohibitively expensive—and Westworld suggests the types of people who might conceivably be able to afford to live forever, and are vain enough to believe they should, are exactly the ones who should stick to their natural expiration date.

In a piece on the industry’s attempts to achieve immortality, a scientist familiar with Calico’s secretive anti-aging experiments told the New Yorker what he thought of those efforts, and in doing so, summed up Westworld‘s argument:

“This is as self-serving as the Medici building a Renaissance chapel in Italy, but with a little extra Silicon Valley narcissism thrown in,” he said. “It’s based on the frustration of many successful rich people that life is too short: ‘We have all this money, but we only get to live a normal life span.'”