Anyone who has run enough years knows the perils of “runner’s knee” or shinsplints. And so running-shoe makers have devoted huge quantities of time and money over the past few decades to developing—and advertising—technologies that are supposed to make for a safer, injury-free run.

One main area of their focus has been cushioning, which is supposed to reduce the force that ricochets up your leg each time your foot hits the ground, leading to an endless series of squishy foams used to make sneaker midsoles. The other big one is motion control. When your foot lands during its stride, it will naturally pronate, or roll slightly inward to distribute the impact. Many people “overpronate,” so footwear manufacturers devised shoes that correct for this issue and force your foot to land in a “neutral” position.

There’s just one problem: There’s no definitive, research-based evidence that either feature actually reduces running injuries, according to Simon Bartold, a well-known sports podiatry and biomechanics expert.

“Where we are in 2018 is we now have a situation where we know pretty conclusively that cushioning has no effect on injury rates whatsoever,” he says. The same goes for motion control, a concept Bartold has previously said should be flushed down the toilet (pdf). ”So we’ve got the two main paradigms of the last 40 years and what all the data is telling us is that neither of these things has any relation to injury.”

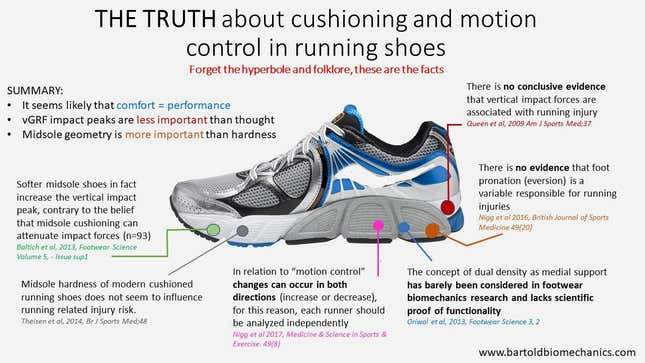

Yet if you walk into a sneaker shop, you can still see shoes loaded with features designed for these purposes. Bartold even created an infographic pointing out some of the components in running shoes today, and what the research says about them.

A self-proclaimed “shoe geek,” Bartold is not an industry outsider. He has consulted for running brand Asics, and a few years ago was recruited by Salomon, a leader in trail running, to head up its expansion into road running. But he’s known not to shy away from criticizing the running industry. In his opinion, marketing has overtaken science.

Indeed, a few years back, a group led by Benno Nigg, another veteran biomechanics expert and industry mythbuster, published a survey of decades of research on running-related injuries. It noted that, despite the supposed advances in footwear over the last 40 years, injury rates haven’t really changed.

The variables most commonly studied in the research surveyed were the impact along your foot from heel to toe when it hits the ground, and pronation—the same issues that cushioning and motion control seek to address. But after reviewing the evidence, the authors concluded that the “two variables that were thought to be the prime predictors of running injuries are not valid.” (The authors noted that many of the studies were small, however, preventing them from drawing perfect conclusions.)

So should we all sprint to the store for minimalist shoes? Not so fast.

The minimalism trend that exploded some years back promised to reduce injuries by returning us to a more “natural” running form, where we land more on the forefoot than the heel. Part of its initial success came from offering a new paradigm at a time when innovation among running sneakers had stagnated—a perfect marketing opportunity.

But it fizzled quickly when injuries didn’t magically disappear. Vibram, which makes FiveFingers, the minimalist shoes with individual toe spaces, even had to settle a class-action suit brought by people who accused the company of making false health claims about the shoes. It agreed not to claim in its advertising that FiveFingers strengthen muscles or reduces injury until there’s scientific evidence to prove it.

Of course, preventing injury isn’t the only intended benefit of a bouncy sole. Some manufacturers tout the energy return their sneakers offer, meaning how much of the force you strike the ground with gets returned to your leg, propelling it up. The idea is that this bounce lets you use less energy per stride, allowing you to run faster for longer. But how well a shoe works for you depends on your individual stride, and heavy foams can nullify any benefit because the weight is making you work more with every step.

So what should a runner look for in a shoe? Nigg’s research suggests that picking the most comfortable shoe is going to be your best option.

Comfort is subjective, and Nigg’s theory hasn’t been tested in controlled experiments. Still, Bartold also believes that, based on the research, comfort should be a factor.

Your best bet is to go talk to an expert at a sneaker shop about what you’re looking for and how you’re going to use the shoe, such what surface you’ll be running on and those sorts of factors. A lot of retailers already offer this sort of service to some degree. Narrow the options down to three pairs. One will probably not feel right straight away, so get rid of that one. Then, of the two remaining, pick the most comfortable one.

He cautions, however, that “runners and the sports-medicine community are looking for a magic bullet” when no such thing exists. There’s nothing wrong with minimalist running shoes or cushioned shoes, but there’s no one shoe that works for everyone or every situation. Our bodies all move a little differently and have different needs. Pay attention to that, and don’t worry about the flashy features and marketing.