Wigtown is a coastal “book town” in Scotland that features an Airbnb rental where bibliophiles can spend their vacation living out the romantic fantasy of running a bookstore. And indeed, according to Shaun Bythell, a year-round bookseller in the same town, it’s deeply romantic work: The evocative smell of books, mixed with cat piss; the customers who openly compare prices on their laptops to Amazon; the book-loving employees, always drunk or severely hungover; the orders for erotica titles such as Tokyo Lucky Hole; and the badgering of aspiring memoirists trying to find a publisher.

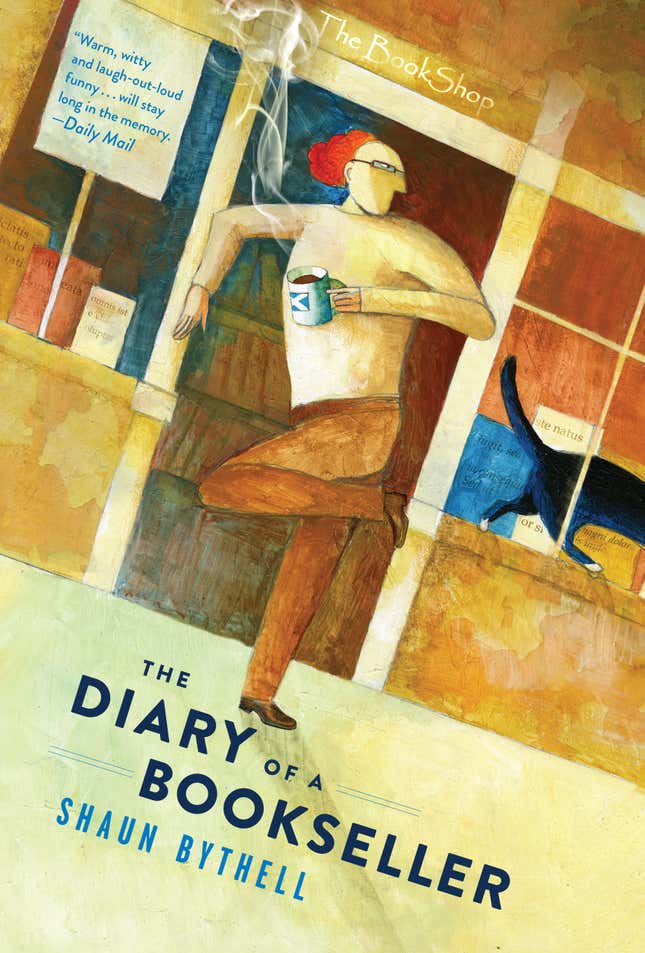

Bythell’s own memoir, The Diary of a Bookseller, is a hilarious read about a dreary year running The Book Shop, a large used bookstore in Wigtown. After a September 2017 UK release, the book comes out in the US Sept. 4 from Melville House.

Bythell took over the store in 2001, at age 31. Starting in early 2014, he kept a daily journal of store happenings for one year. It’s a cheerfully depressing account of independent bookselling today—deadpan, ruthless, poignant, and at times, so charming it’s almost unbelievable.

Bythell’s main antagonist is also his only regular employee, a Jehovah’s Witness named Nicky. The two are locked in a weekly battle of mutual torment, Nicky moving On the Origin of Species to the fiction section, and Bythell retaliating by placing the Bible with novels. On Fridays, Nicky brings him dubious food scavenged from dumpsters—egg custard tarts she’s sat on, or expired packaged cake. One week’s treat “looked like something from a hospital clinical waste bin.”

The larger cast of characters in Diary of a Bookseller are so zany and absurd they would seem over-the-top in a 1990s movie about an indie record shop. There’s Sandy, the most tattooed man in Scotland, according to Bythell, who barters walking sticks for store credit; Smelly Kelly, the cologne-soaked man in dogged pursuit of Nicky, who has made it clear she’s not interested; and Eliot, Bythell’s friend who tends to discard his shoes somewhere in the store within 10 minutes of arrival.

Bythell is often as charmingly unlikeable as his customers, ridiculing them in the book and online. It’s not clear that he’s actually helpful. He routinely receives complaints about unfulfilled or switched book shipments. His employees appear mostly incompetent.

The circus aside, the book is rich with information about the business of bookselling, including a description of an ingenious online scam to reduce book prices. Bythell saves his deepest rancor for Amazon (though he uses it to fulfill online orders), which has hit him and other small and medium-sized used booksellers particularly hard. His contempt is made apparent one day in August, when he receives a complaint about a late book. Bythell goes to his parents’ house to borrow a shotgun and then shoots a used Kindle he bought on eBay for £10. (Footage of the target practice is admittedly satisfying.) He mounts the mangled e-reader in the store.

The Diary of a Bookseller doesn’t seem like it should work. Life at The Book Shop is boring. On a typical day Bythell might sell £200 worth of books, once as little as £5. But there is a soothing monotony to the rhythm of his days. Bythell somehow creates a sense of urgency in the nothingness, and readers may feel that if they skip even one day, they’ll miss some winningly cutting remark.

Part of Bythell’s job is to drive to people’s houses, often to look at book collections of recently deceased people. He has to figure out what to salvage and how to value their legacies, in the form of the books they’ve left behind. It’s very gloomy. But there’s something surprisingly touching about the entire enterprise.