Last month, Netflix claimed that 45 million people had watched its horror-thriller Bird Box. Yesterday Nielsen confirmed that the film is indeed a hit: 26 million people in the US alone watched Bird Box in the week after its Dec. 21 release, according to the audience measurement firm. That’s nearly the number of Americans who bought a ticket to see Aquaman, one of the highest-grossing films of 2018.

Both movies—two of the biggest hits of the year—owe a lot to writer H.P. Lovecraft and the brand of cosmic horror he helped develop a century ago.

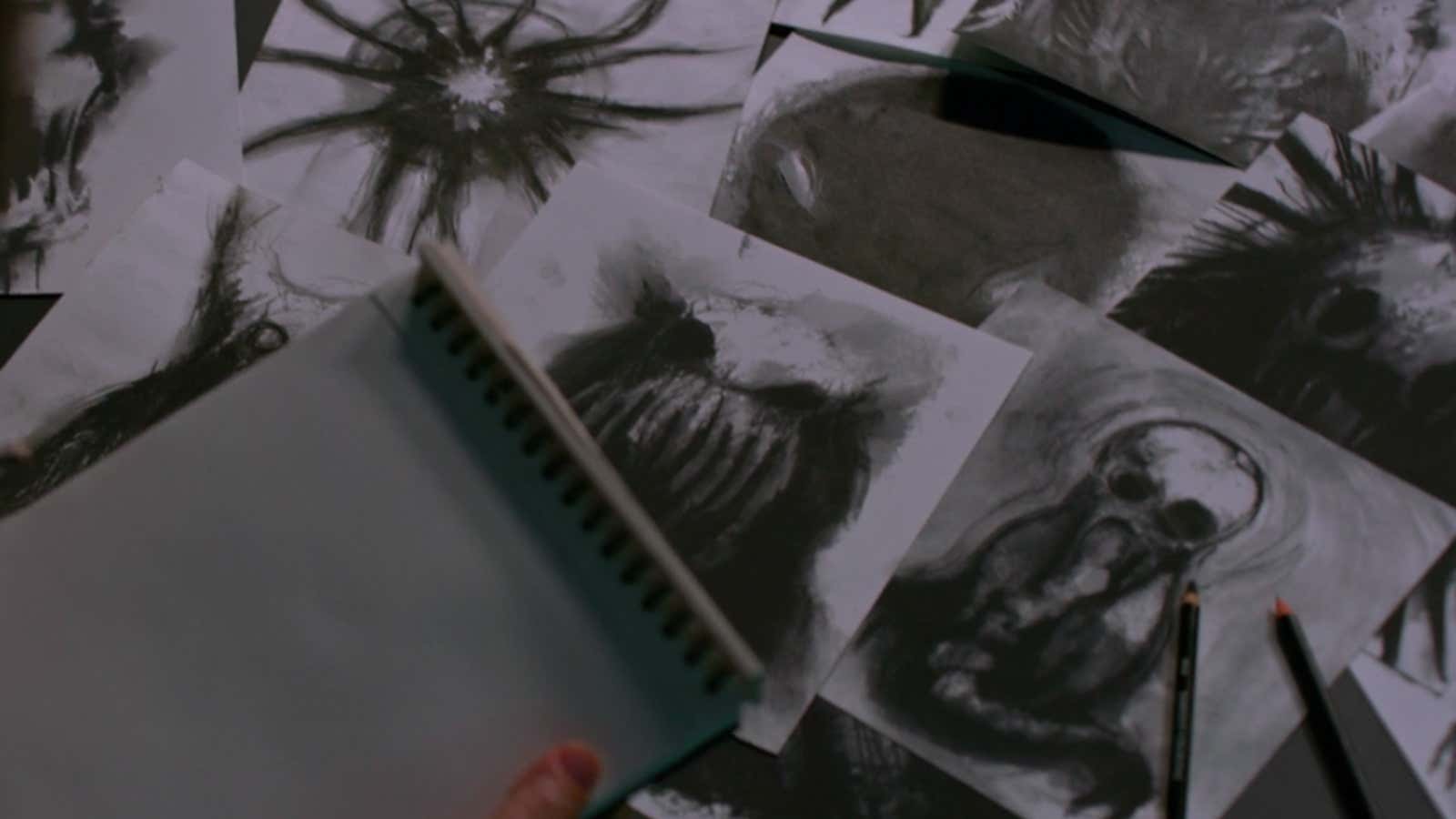

Most of Lovecraft’s short stories, from “The Call of Cthulhu” to “At the Mountains of Madness,” follow man as he is confronted with the knowledge that there exists something else in this universe, something so incomprehensibly vast and terrible that the mere awareness of its existence is enough to drive even the most rational person to madness. Some Lovecraft characters commit suicide shortly after coming into contact with these things, which often take the form of grotesque creatures whose physical forms can neither be grasped nor fully articulated by humankind.

In “Dagon,” the narrator chooses to jump from his window rather than spend another moment in a world in which the hideous monster he saw also exists. “When you have read these hastily scrawled pages you may guess, though never fully realize, why it is that I must have forgetfulness or death,” he tells readers shortly before he chooses death. In “Nyarlathotep,” all of civilization descends into chaos when it encounters the titular god, a shape-shifting, inconceivable terror who’s come to bring doom upon the world.

Sound familiar? Cosmic horror is at the root of Bird Box, which essentially marries the basic premise of “Dagon” with the apocalyptic scale of “Nyarlathotep.” Based on the book by Josh Malerman, the Netflix film follows a new mother (Sandra Bullock) as she attempts to navigate a world in which people immediately go nuts and kill themselves upon seeing unknown creatures. In order to avoid that awful fate, they are forced to blindfold themselves whenever venturing outdoors.

Some might argue that Bird Box is actually “Lovecraftian Lite“: It employs many of the cosmic tropes that Lovecraft’s work is famous for, but in a decidedly more optimistic story that resists the utter hopelessness that defined the author’s cosmic philosophy. Lovecraft is known today as a racist, xenophobe, and anti-semite, whose poisonous worldview seeped into his writings. His characters’ primal fear of the unknown—and of things different from them—paralleled the author’s own fear of immigrants and non-white people. If he were alive today, Lovecraft might be writing for Breitbart or running Donald Trump’s homeland security department.

Racist though he was, Lovecraft’s imprint on horror was undeniable, and his literary philosophy has lived on to the present day. The “Mind Flayer“—a massive, spider-like telepathic entity that plagued the second season of Stranger Things—is clearly an homage to the eldritch creatures of Lovecraft’s universe. Everything from Annihilation to recent reboots of It and Ghostbusters to the video game World of Warcraft dabbles in cosmic horror.

Aquaman is filled with Lovecraft references, both explicit (a copy of The Dunwich Horror can be seen on a coffee table in the film) and less obvious (minor spoilers: a terrifying undersea creature with whom Aquaman does battle is reminding viewers of Cthulhu). Director James Wan, an Australian of Malaysian Chinese descent, cleverly subverts the racist author who influenced the movie by making Aquaman—a half-human, half-Atlantean played by an actor of mixed heritage (Jason Momoa)—the hero who saves us all.

Why Lovecraft is having a moment right now isn’t entirely clear, but one explanation is that cosmic horror is really just a heightened version of the anxiety of living in uncertain times many feel today. We haven’t had to face Dagon or Nyarlathotep (yet), but the acknowledgement of global upheaval—that the world isn’t quite what it seemed only a few years ago—is enough to drive some of us a little cuckoo. That may be especially true for the many Americans still trying to understand their new political reality.

You don’t have to be religious to believe that, on a very basic level, there could be forces at work in this universe (or some other one) that we don’t and perhaps won’t ever understand. Cosmic horror taps into that ongoing uneasiness and turns it into entertainment. Perhaps the reason Bird Box was so popular wasn’t because of the memes, but rather the spooky, gnawing idea that we’re not alone in this existence, that there’s something else among us, rising to the surface.