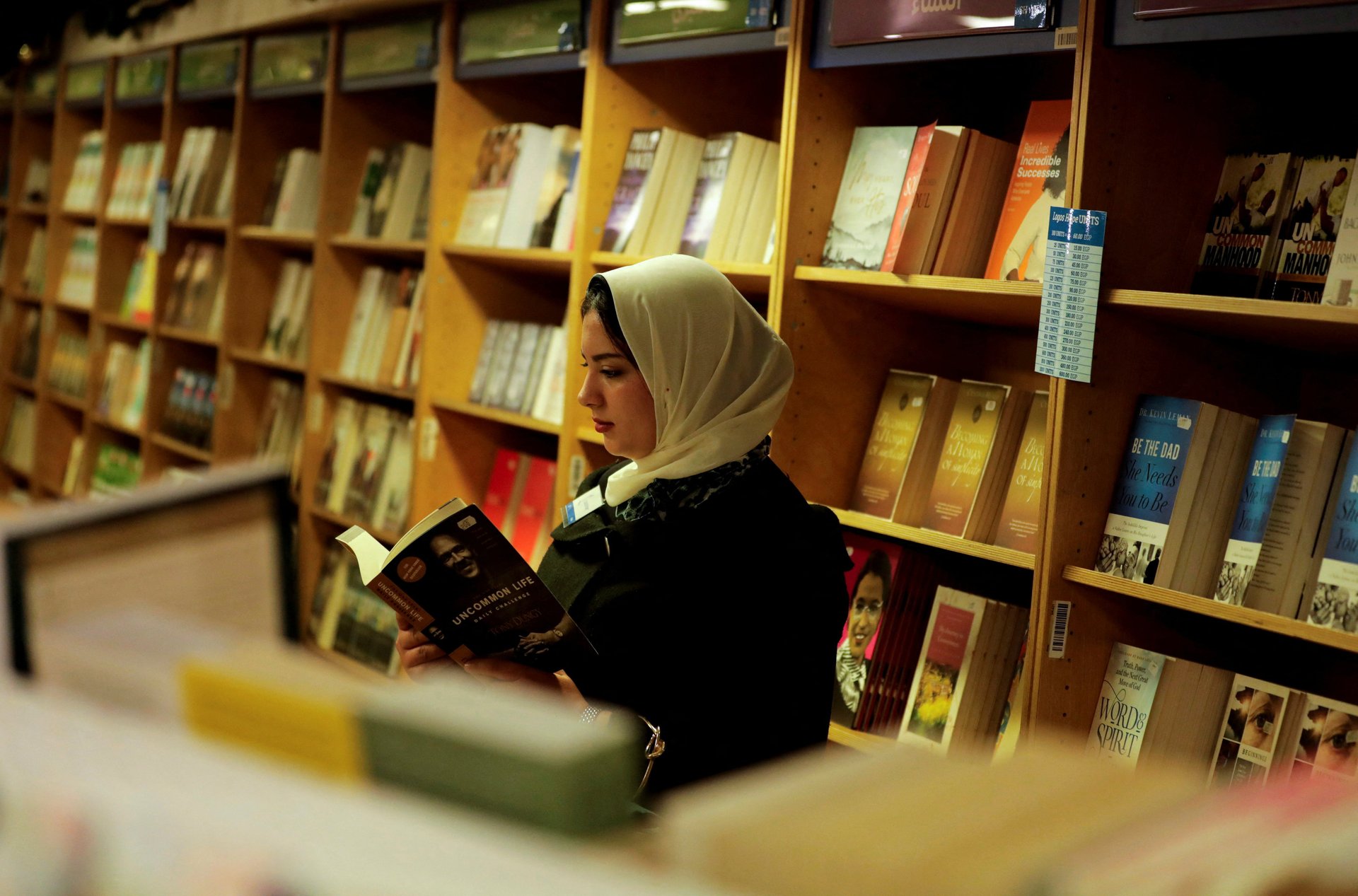

Women are now publishing more books than men—and it's good for business

Women have gone from publishing just 18% of books in the 1960s to more than half today, driving up revenue and diversifying readership

It’s relatively easy to count female CEOs at Fortune 500 companies, chart women in the workforce, or measure the gender pay gap. But when it comes to intellectual property (IP)—the ideas that drive creative works—it can be harder to divine who is doing what (versus, for example, who is taking credit.)

Suggested Reading

Joel Waldfogel, an economist at the University of Minnesota, set out to study book publishing to gain insight into how much women and men have contributed to the number of books published in the last 70 years. Waldfogel found that by 2020, for the first time in history, women were publishing more books than men, leading contributing to increased revenue for the industry for both male and female consumers. US book publishing generated $29.3 billion in 2021, according to the Association of American Publishers, a year-on-year increase of 12.3%.

Related Content

“While women’s participation in IP creation continues, generally, to lag men’s, the past half century has brought a revolution in gender-inclusive book creation,” Waldfogel wrote in a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) in February 2023.

By analyzing data from Goodreads, Bookstat, Amazon, and the National Library of Congress, Waldfogel found that women’s share of published titles increased from around 20% in the 1970s to over 50% by 2020. This likely displaced some male authors, but the change wasn’t just that male authors were replaced by female authors. Rather, the whole industry grew, and by 2021, female-authored books sold more copies on average than those written by men.

Books do more than make money

Waldfogel’s paper used revenue as a proxy, along with a few other measures, to discover the “welfare” effect of books: how much they benefited those who read them. He concluded, overall, that the influx of female authors increased the welfare of a diverse set of readers, by offering them things they wouldn’t have been able to get had the female influx not occurred. These books might, for example, have offered narratives and perspectives that would otherwise have gone unwritten. Revenue overall rose by between a tenth and a fifth with the influx of female authors, he found.

The study has some limitations. Waldfogel determined female and male authorship by first name, which risked misclassifying some authors with names that don’t easily fall into either gender bracket. Since Waldfogel is looking at an large aggregates, he notes, these individual discrepancies shouldn’t matter. But it does raise the question of how the study counts an author like JK Rowling.

Overall, though, Waldfogel’s conclusions are hopeful both for book publishing and female writers: It’s a bigger, better industry due to their presence, and readers still love to read.