Much has been made of the ways a four-day work week could increase productivity and worker satisfaction. But the shift could also be a huge win for gender equality.

The Wellcome Trust, one of the world’s biggest funders of scientific research, announced last week that it is considering a four-day week for its head office staff, a plan that could make it the largest global employer to experiment with the policy.

Wellcome, which was founded in 1936 and now has an investment portfolio totaling £26 billion ($33.6 billion), employs about 800 people at its UK headquarters. It plans this year to trial giving staff the option to move to a shorter week with no less pay. The idea aims to increase the impact of the trust’s work while improving employee happiness, Wellcome said.

“Moving to a four-day week is one of a number of very early ideas that we are looking at that might be beneficial to welfare and productivity for everyone at Wellcome,” Ed Whiting, Wellcome’s director of policy and chief of staff, said a statement. “It will be some months before we can consider a formal decision and we’re carefully considering the potential impact it could have.”

The impact on gender equality could be one of the most interesting findings.

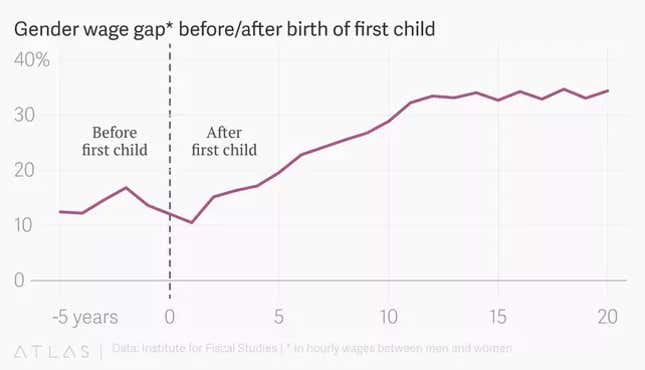

The gender pay gap starts to expand after women have children. At first, both parents’ incomes take a knock, but men’s quickly recover. Women’s never do. The “motherhood penalty” is reflected in a woman’s lower pay—and often lower status at work—throughout her career. By the time a child is 12 years old, the gap is 33%, according to the UK’s Institute for Fiscal Studies:

A big part of the reason women are paid less than men is that they often work fewer hours after children are born, prioritizing childcare over forging forward in a full-time career. But there are many other factors at play. Parental leave policies, in most countries that have them, either mandate more leave for women, or make it possible for partners to choose who takes leave. But cultural norms often mean that an employer will look more favorably on a woman taking baby leave, while a man’s will make it harder, and place more conditions on it. Moreover, since men are often already in higher-paying jobs, many couples make a financial equation: They’ll lose less money if it’s the man who returns to work.

When women go back to work, couples and companies may not even notice they’re perpetuating norms, and firming up the foundation for wage discrepancies in the process. As Quartz reporters Corinne Purtill and Dan Kopf write: “Is a woman cutting back on her hours because she prefers to go part time, or because the division of domestic labor established during maternity leave isn’t manageable with a full-time job? Do women decline management opportunities because they’re not interested, or because a partner’s inflexible schedule and higher wages make any compromise impossible?”

A four-day week, such as that proposed by Wellcome, could have a profound gender effect. Women at the company who have children will be free to spend one day a week with them and, crucially, remain on the same footing as the rest of their colleagues. And the radical change could extend beyond the Trust’s own staff: Men with kids at the company would be able to commit to a day of childcare as well, meaning that their partners would be freer to make their own choices about part-time vs full-time work.

🎧 For more on the benefits of a shorter week, listen to the Work Reconsidered podcast episode on the four-day workweek. Or subscribe via: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher.

Trade unions have begun calling (paywall) for shorter weeks in the UK, and there’s some global precedent. New Zealand-based estate-planning firm Perpetual Guardian instituted a four-day week for its 250 staff last October. A trial of the policy found that staff stress levels reduced by seven percentage points. In designing the trial, the company worked with academics to find ways staff could be more productive, including automating some processes, and eliminating non-work internet use.

Andrew Barnes, Perpetual Guardian’s founder, said in an email to Quartz that society needs to have “a broader conversation about modern working hours and conditions and how they affect family life.”

“When senior executives are doing a four-day week, one facet of the glass ceiling holding women back is removed,” Barnes said. “It improves the gender balance, closes the pay gap, and offers more flexibility to allow for family and childcare obligations.”

Some, like Laura Carstensen of Stanford University, argue that working less intensively at the points in careers when people are busiest, for example with young children, makes so much sense that we should push any full-time working later in life. What’s special about the four-day week experiment is that it mandates a change for all workers, in the process leveling the gender-playing field in a more meaningful way than unconscious bias training, hiring policy changes, or pay reviews have yet managed.

This story was updated to include comment from Perpetual Guardian founder Andrew Barnes.