Shortly after Joko Widodo became the president of Indonesia in 2014, he set about attacking illegal fishing in the nation’s vast waters. Conducted mostly by foreign trawlers, he noted, it cost Indonesia about $20 billion a year in lost revenue. His “shock therapy” solution: Blow up foreign trawlers caught trespassing in Indonesian waters, and publicize the dramatic explosions.

Now Malaysia plans to follow suit, albeit with less of a bang. Agriculture minister Ahmad Shabery Cheek, after attending a fisheries summit in Jakarta last week, said Malaysia will also start sending vessels to the seabed. The sunken hulls will serve as artificial reefs that will, by offering protection, allow fish to breed and increase their numbers. Malaysia, however, will skip the explosives, which can kill marine life and cause other environmental damage. How exactly it plans to sink illegal boats was not specified.

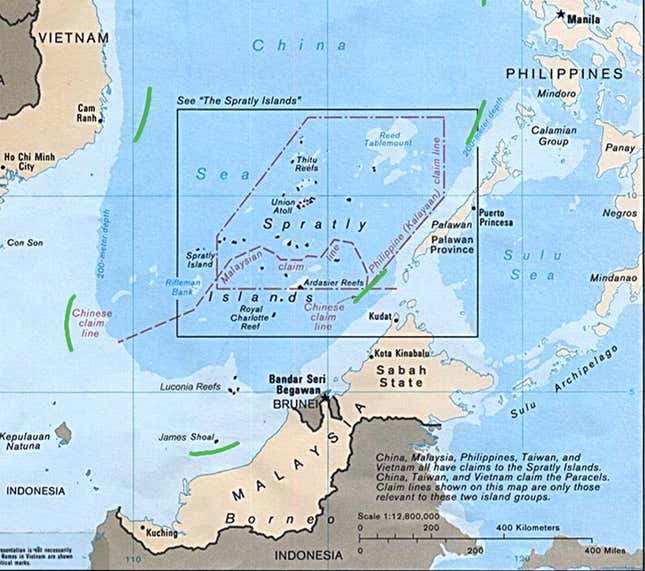

Of particular concern for both nations is China. The giant neighbor wants to become a major maritime power and claims nearly the entire South China Sea as its own, based on a “nine-dash line” drawn on a 1940s map. A ruling last month invalidated the claim under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), but Beijing has vowed to ignore it and has belittled the tribunal behind it.

In the case of Malaysia, that means it can expect a Chinese presence in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending from its portion of northern Borneo, also known as East Malaysia. Under UNCLOS, Malaysia should have sole extraction rights to all the natural resources extending 200 nautical miles from the coastal baseline.

Falling within both Malaysia’s EEZ and the nine-dash line is Luconia Shoals, an area of reefs and islets rich in marine life and, under the seabed, oil and gas reserves. Malaysia complained about (paywall) the presence of Chinese coastguard ships in the area in June 2015. A year later, one such ship made aggressive moves toward a Malaysian patrol boat, after reports in March of about a hundred Chinese fishing vessels operating in the area.

Another point of overlap is James Shoal, which Chinese students are taught in grade school is the southernmost point of China.

Of course not every trawler trespassing in the EEZs of Malaysia or Indonesia is Chinese. But China’s size, power, and systematic approach make it a big concern.

Beijing ensures that its ”fishing militia,” at the vanguard of defending its territorial claim, receives not only subsidies but also strong logistical support. In April Vietnamese authorities apprehended what looked like one of the many Chinese fishing vessels that work illegally in their EEZ. But they soon discovered it was a disguised refueling ship serving Chinese trawlers. And when Indonesia tried to apprehend a Chinese fishing trawler in its EEZ in March, a Chinese coastguard ship physically interfered.

China has new infrastructure in the sea that will help it support its fishing militia. It’s rapidly built artificial islands atop reefs, fitting them out with buildings, lighthouses, and deep-water ports (how well these structures can weather the typhoon season remains to be seen). And this week China opened a new fishing port near Sanya on Hainan Island. Able to berth 800 (and eventually 2,000) vessels, the facility will be central to “safeguarding China’s fishing rights in the South China Sea,” said Zhang Huazhong, head of the Sanya fishery bureau.

Beijing gives its fishing militia legal and diplomatic support, too. This week China’s supreme court announced that foreign fishermen caught operating in its waters will be criminally prosecuted, and could spend up to a year in prison. It’s unclear at this point how far Beijing will take that—will Southeast Asian fishermen be arrested for operating in their own nation’s EEZ?—but it seems clear that Malaysia, Indonesia, and others can reasonably expect more intrusions from China’s fishing militia.

In this context the appeal of Indonesia’s strategy becomes clear. Sinking illegal fishing vessels sends a message, defends a nation’s exclusive economic zone, and encourages more breeding of the very fish that the trespassing fishermen would heedlessly over-harvest.

In April, Indonesia blew up 23 such boats, synchronizing and live-streaming the explosions from different locations for maximum effect. On Aug. 17 it will sink dozens more to celebrate Independence Day, as it’s done the past few years. According to Cheek, the agricultural minister, such actions have contributed to more bountiful catches for Indonesian fishermen. He’s hoping their Malaysian counterparts will enjoy a similar boost in the coming years.