Apple has never been first on anything and it isn’t about to change now

Over the past week, thousands of designers, developers, and engineers, along with a few reporters, crammed into concrete convention center to hear what’s next for Apple at the company’s annual developer conference. Many went to learn how to build better apps and programs for iPhones, iPads, and Macs; some went to network with like-minded people similarly hoping to become the next Silicon Valley success story. Others just wanted to see what aluminum-cased objects Apple will be selling in the near future.

Over the past week, thousands of designers, developers, and engineers, along with a few reporters, crammed into concrete convention center to hear what’s next for Apple at the company’s annual developer conference. Many went to learn how to build better apps and programs for iPhones, iPads, and Macs; some went to network with like-minded people similarly hoping to become the next Silicon Valley success story. Others just wanted to see what aluminum-cased objects Apple will be selling in the near future.

There was lots to talk about: promised software updates, a refreshed line of Mac computers, toolkits for developers to build augmented-reality apps, and a few new partnerships that might hint at where the company is headed. But much of the media attention went straight to the new smart-home speaker Apple unveiled during its keynote address Monday, the HomePod.

The interest in the squat, mesh-covered device was understandable, for reasons beyond the world’s insatiable hunger for Apple innovation. The company’s last attempt to enter the speaker market, a decade ago, was widely received as a dud, and in the time since it has been lapped by competitors. The first true hit product of its kind was the Amazon Echo, first released for Amazon Prime subscribers in late 2014, while Sonos and Bose have held onto their dominance in the connected home speaker market. Just catching up with the competition might have been seen as an accomplishment, even if just a modest one.

But Apple didn’t release the HomePod as a me-too product. It’s meant to be a game-changer in how people listen to music at home, just as the iPod reinvented the concept of portable music with the release of the iPod almost 16 years ago.

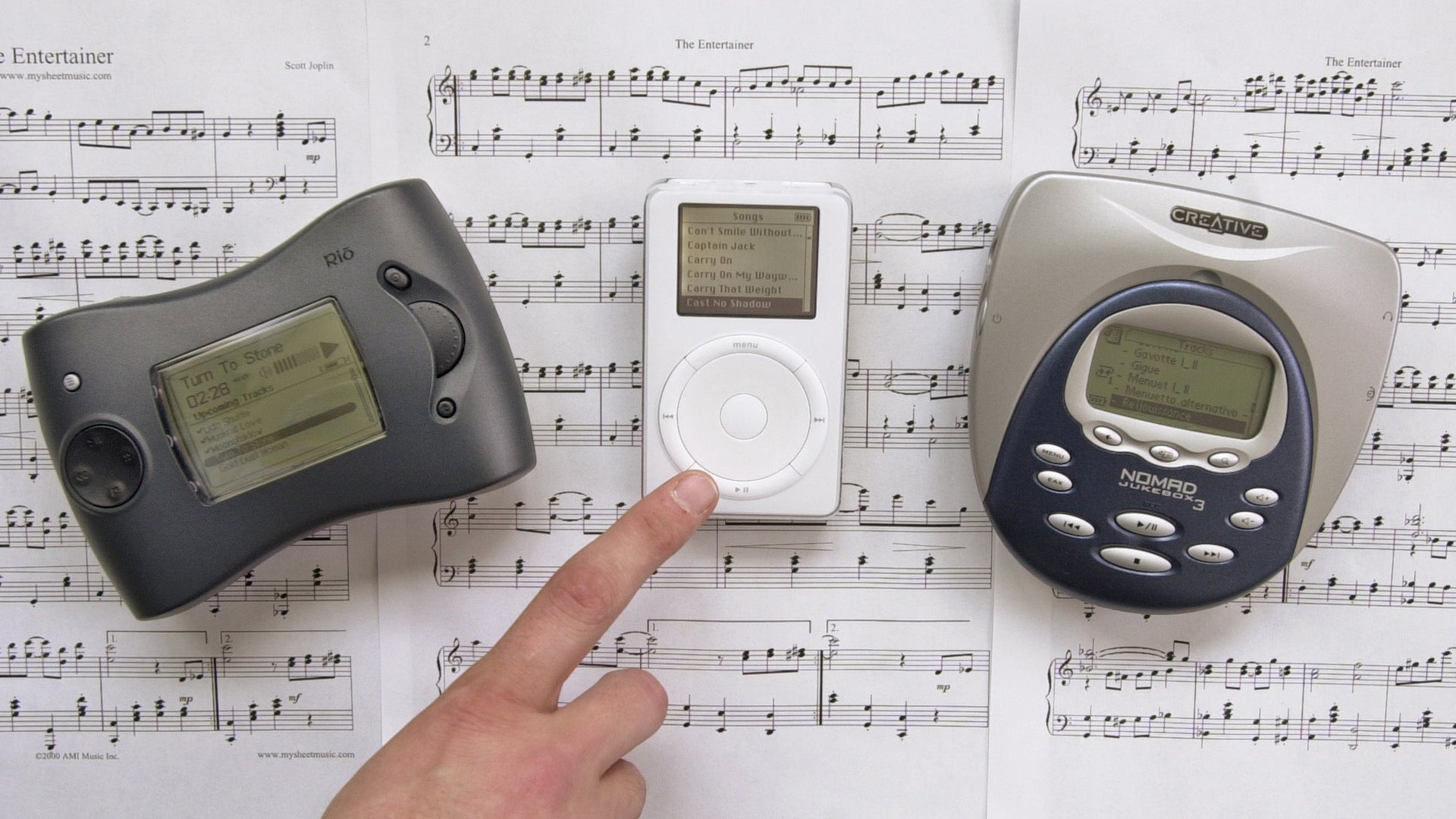

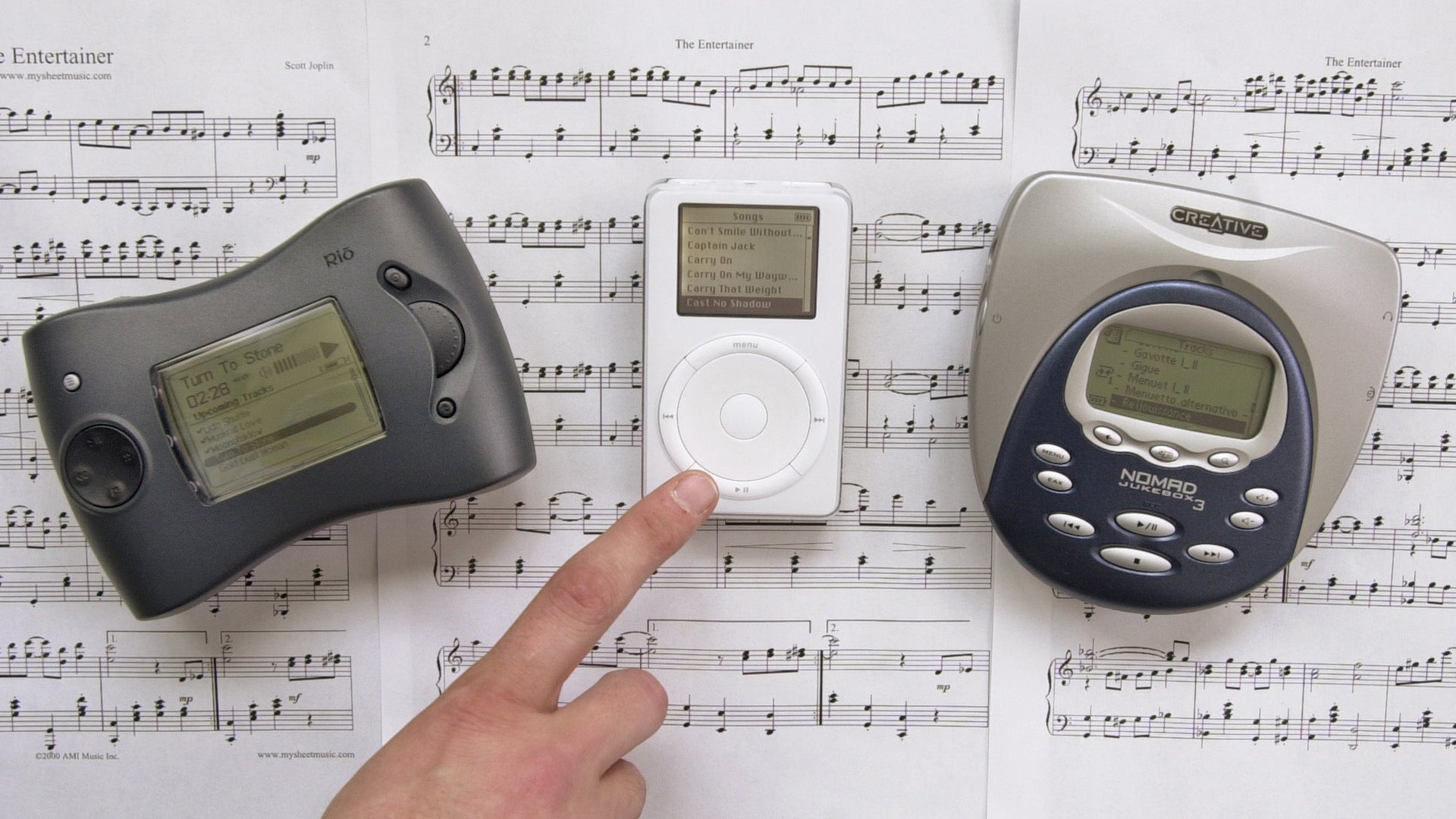

Though Apple seemed to singlehandedly conquer the music world with its monolithic-white-rectangle-and-earbuds sets, the success of the iPod was built on the portable music players that came before it. Arguably the first successful one was the Diamond Rio PMP300, a surprise hit in the 1998 holiday season, selling 200,000 units at a time when many people were still transitioning from tape decks to portable CD players. The Rio was released three years before first iPod and four years before the first iPod that worked with Windows computers, the latter of which opened the device up to hundreds of millions of Microsoft users. Apple did spur one completely revolutionary idea with the iPod, however—the atomization of the music album—by selling song downloads for $1, which essentially kickstarted the current streaming-music era (along with pirate sharing networks like Napster).

This has generally been Apple’s strategy since Steve Jobs retook the helm of the company in the late 1990s: Approach established markets and dominate them with simpler products that are better built and marketed. The plan for the HomePod won’t be any different.

Regardless of whether you think that Apple has lost its way since CEO Tim Cook took over from Steve Jobs, the strategy has pretty clearly stayed the same. Microsoft and Samsung release a tablet with a keyboard; so will Apple. Samsung and others release large smartphones and small tablets, so will Apple. Samsung and FitBit release smart wearables, so will Apple. Samsung and others release wireless earbuds, so will Apple. (You might be noticing a trend here.)

Not every recent product announcement from Apple has felt as stark as when Jobs first told the world that one of the original personal computer manufacturers would be entering the portable music player business, but each has followed a similar trajectory. It’s too early to say whether the HomePod, or any of the new pieces of software Apple announced this week, will be as massive a success as the iPod, iPhone, or even the iPad have beenin the past, but given that even Apple’s “Other Products” bucket (which includes the Apple Watch and AirPods) is the size of a Fortune 500 company—it generated nearly $11 billion in revenue in 2016, though it is the company’s smallest business segment—there doesn’t seem to be any good reason for Apple to change its approach to new products now.

Apple has been criticized of falling behind in the emergent technologies of recent years, such as artificial intelligence, augmented reality, virtual reality, and self-driving cars. But Apple has been shown to be working on all of these technologies. It has registered vehicles with the California transportation department to test self-driving cars; it spoke at length about its machine-learning efforts at its developers conference (and has held meetings at AI events in the past), and had working demonstrations of both VR and AR applications running on Apple products at this year’s developers conference, with the intention that developers will build products off these new capabilities.

Will that be enough to satisfy the skeptics? Cook sounded doubtful about that, if also unfazed by it, in an article published Friday in MIT Technology Review.

Cook says the fact that the press doesn’t always give Apple credit for its AI may be due to the fact that Apple only likes to talk about the features of products it is ready to ship, while many others “sell futures.” Says Cook: “We are not going to go through things we’re going to do in 2019, ’20, ’21. It’s not because we don’t know that. It’s because we don’t want to talk about that.”

This has been Apple’s standard operating procedure as long as the iPod has been in existence. When Apple is still breaking its own records with the cash it’s bringing in, why change?