The faces of Hong Kong: A timeline of the 20 years since the handover

Just past midnight on July 1, 1997, Chris Patten, the last governor of the Crown Colony, sipped a glass of red wine as he sailed away from Victoria Harbor on a royal yacht in driving rain. About an hour later, Tung Chee-hwa, a former shipping magnate, took his oath of office before Chinese premier Li Peng and became the first chief executive of the new Hong Kong Special Administration Region. The British flag came down and China’s flag and a new Hong Kong flag were hoisted. Far away on the mainland, fireworks exploded over Tiananmen Square.

Just past midnight on July 1, 1997, Chris Patten, the last governor of the Crown Colony, sipped a glass of red wine as he sailed away from Victoria Harbor on a royal yacht in driving rain. About an hour later, Tung Chee-hwa, a former shipping magnate, took his oath of office before Chinese premier Li Peng and became the first chief executive of the new Hong Kong Special Administration Region. The British flag came down and China’s flag and a new Hong Kong flag were hoisted. Far away on the mainland, fireworks exploded over Tiananmen Square.

And with that, China resumed control of Hong Kong, ending more than 150 years of British colonial rule. Under the “One Country, Two Systems” formula, which Chinese president Jiang Zemin promised in his handover speech would be implemented “unswervingly,” Hong Kong was to retain its capitalist financial market, freedom of expression, and partial democracy—for at least 50 years. For many in Hong Kong, the two decades of that bold experiment appears to be a creeping process of “one country” overriding “two systems” everywhere from politics and human rights, to the economy and language.

When it comes to Hong Kong’s economy, Chinese companies are now beginning to crowd out local and foreign firms in industries like banking and real estate. Dissidents who openly rally for democracy—or make material taboo in China available—have increasingly been retaliated against. Many have long derided the city government as the tool of Beijing and now also fear Hong Kong’s independent judicial system is at risk. The biggest disappointment so far has been the failure to open up voting for the chief executive, leading to mass protests in 2014.

Here’s a look back at the highs and lows Hong Kong has experienced over the two decades since the handover, told through the people and moments who more often than not reflect the tensions of an increasingly complicated Hong Kong-China relationship.

1998

Billionaire George Soros successfully bet against the currencies of Thailand and Malaysia during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, but was forced to walk away from Hong Kong with losses the next year. That was largely thanks to the dapper then-financial secretary Donald Tsang, who went on a HK$118 billion ($15 billion) stock-buying spree to defend the Hong Kong dollar’s peg against the US dollar.

In 2005, when Tung, the first chief executive of the SAR resigned after losing the confidence of both Hong Kong people and the central government, Tsang became the city’s No. 1 official. Earlier this year, the 72-year-old Tsang was sentenced to 20 months in jail on a corruption offense that occurred just before his retirement in 2012.

1999

Property tycoon Li Ka-shing was ranked by Forbes as Hong Kong’s richest person for the first time in 1999 (link in Chinese), and has since retained the top spot for 19 straight years (he’s also among the world’s richest, usually somewhere around the top 20).

Li’s family fled China for Hong Kong during the Sino-Japanese war, and his father died soon after. In 1950, he established a factory to make plastic flowers and then began to invest in real estate. His flagship company, Cheung Kong Property Holdings, is currently the world’s third-largest property developer by market value. Nicknamed “Superman” for his business prowess, the nearly 89-year-old recently denied reports that he’ll retire as chairman from his global conglomerate, CK Hutchison Holdings, by next year.

Despite his rags-to-riches story, Li is also seen as a symbol of the hold a handful of companies have on Hong Kong’s economy, in everything from phone and internet service to real estate. Competition from Chinese developers hasn’t helped, though, instead driving up prices in the world’s most unaffordable housing market.

2000

On August 2, 2000, a group of mainland Chinese who sought the right to permanently stay in Hong Kong started a fire at Immigration Tower, leading to the deaths of a senior official and one of their group. Leading protester Shi Junlong was sentenced to eight years in prison (link in Chinese) for manslaughter.

Shi was extradited to China after completing his sentence. But he became a Hong Kong resident in 2011 under the “one-way permit” scheme that allows mainlanders to reunite with their families in Hong Kong. Created in the 1980s, the special program is administered by mainland authorities, and Hong Kong has no say in whom it takes.

2001

Anson Chan served as Hong Kong’s chief secretary for nearly a decade under both British and Chinese rule. In 1962, Chan was one of just two women to enter the civil service. Three decades later, Chan became the first woman and ethnic Chinese person to hold the second-highest government position in Hong Kong.

Chan voiced greater support for democracy and free speech than her Beijing-backed boss, Tung—when she resigned in 2001, many in Hong Kong thought it was due to these differences. Her stance earned her the nicknames “Hong Kong’s conscience” and “Iron Butterfly.”

2002

In September 2002, the Hong Kong government introduced its first proposal under Article 23 of the Basic Law, which authorizes the local administration to pass laws covering treason and sedition. Regina Ip, then-security secretary, was perhaps the most vocal supporter of the security bill. After the proposal was withdrawn the following year amid massive public protests over fears that human rights and freedom of assembly would be hit, Ip resigned from her post, citing “personal reasons.”

In 2012 and 2017, Ip ran for the chief executive elections, but didn’t get enough votes to enter the races. During her 2017 campaign, she pledged to enact Article 23 in “suitable measures” if elected.

2003

This was a mournful year for Hong Kong: the outbreak of SARS, or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, took 299 lives in the city and sowed widespread panic.

Tse Yuen-Man was the first public hospital doctor to die from SARS. The 35-year-old woman, who volunteered to work with SARS patients at Tuen Mun hospital, was infected with the virus when she tried to resuscitate a patient.

In 2003, Hong Kong also lost two Cantopop legends, Leslie Cheung and Anita Mui. Cheung, suffering from depression, jumped to his death from the Mandarin Oriental hotel in Central on April Fools’ Day, while Mui died at the end of the year after a battle with cervical cancer.

2004

Leung Kwok-hung, nicknamed “Long Hair” for his mane, is a longtime democracy activist in Hong Kong. In 2004, Leung was elected to the Legislative Council for the first time, and still sits in the legislature today.

Leung, who models himself on Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara, never shies away from confronting the central and Hong Kong governments. He has been jailed numerous times for holding public protests. Security guards have at times dragged him away for disrupting top officials’ speeches. Beijing has more than once banned him from entering the mainland.

2005

Thousands of anti-globalization activists from across the globe flooded Hong Kong in December 2005 to protest against the World Trade Organization summit. One category of protester stood out: the South Korean farmer, fiercely opposed to efforts to open the country’s agricultural market. (About as many police mobilized to thwart anti-globalization protesters then as to secure the city this week for president Xi Jinping’s visit.)

Farmer protests escalated into the fiercest fighting to happen in the city for decades. On Dec. 17, police used water cannons, tear gas, and pepper spray to disperse farmers who tried to breach police cordons.

2006

Joseph Zen, an outspoken critic of Beijing, was a bishop of Hong Kong for over six years. In February 2006, Zen was selected by Pope Benedict as one of his 15 new cardinals. China, which installs its own bishops without the Vatican’s approval, later denounced the promotion as a “hostile act.”

In 2016 Zen warned against allowing the Communist government to have a hand in selecting bishops, as the Vatican and Beijing was reportedly in talks of a deal. “[T]he diplomats in the Vatican… are typical diplomats. They just want to achieve something, to succeed, have agreements with governments at all costs,” Zen told Quartz. “But I do not see any reason to be optimistic about the Church in China.”

2007

In January 2007, Margaret Chan, Hong Kong’s former health director, began her decade of work as the World Health Organization’s (WHO) director-general. An expert on SARS and bird flu, Chan became the first Chinese person to lead a United Nation agency, after being elected in late 2006. Chan was later heavily criticized for the WHO’s slow response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

The year also marked the last hurrah for Hong Kong investors before the global financial crisis that began in 2008 took its toll: the benchmark Hang Seng Index hit its all-time high of 31,638 points in October. The year saw the city’s bankers and hedge fund titans organize boxing matches—Hedge Fund Fight Night—at five-star hotels. For charity, of course.

2008

As a small, open economy and Asia’s financial center, Hong Kong was inevitably hit hard by the global financial crisis. By the close of the year, the Hong Kong securities market had plunged 50% (pdf) compared with the year before, wiping out more than HK$10.2 trillion ($1.3 trillion) in market capitalization. Home prices fell nearly 20% (pdf) from their peak the year before. In the last quarter of 2008, Hong Kong’s GDP slipped into a contraction of 2.5%, the worst performance since 1999.

The same year, a pop star accidentally sparked a public debate about sexual morality in Hong Kong and the mainland after photos of him in sex acts with female celebrities were leaked online. Singer Edison Chen made a public apology, especially to the women involved, and said he was stepping away from the Hong Kong entertainment circle “indefinitely.” A computer technician was eventually jailed for eight and a half months for stealing the photos when he took Chen’s laptop for repairs.

2009

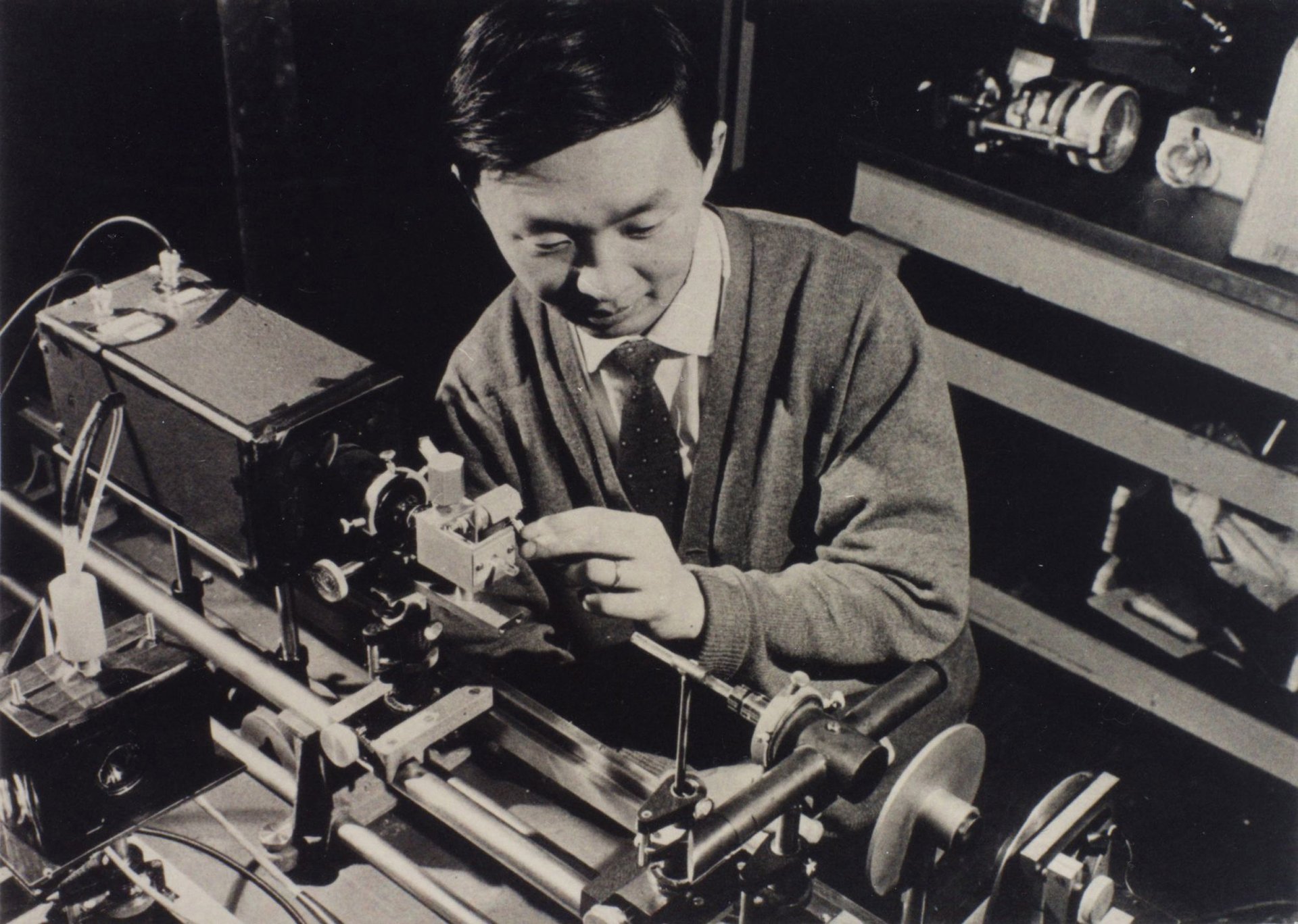

Hong Kong physicist Charles Kao, dubbed the “father of fiber optics communication,” was jointly awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics.

In 1966, Kao developed a fiber optic wire that was able to carry as much information as is contained in 200,000 phone calls, giving rise to many of the communication products now taken for granted.

2010

In January, a group of opposition legislators known as the five pan-democrats collectively resigned to force a special election that would pit pro-democracy candidates against pro-Beijing ones in what they hoped would be a de facto referendum on democracy.

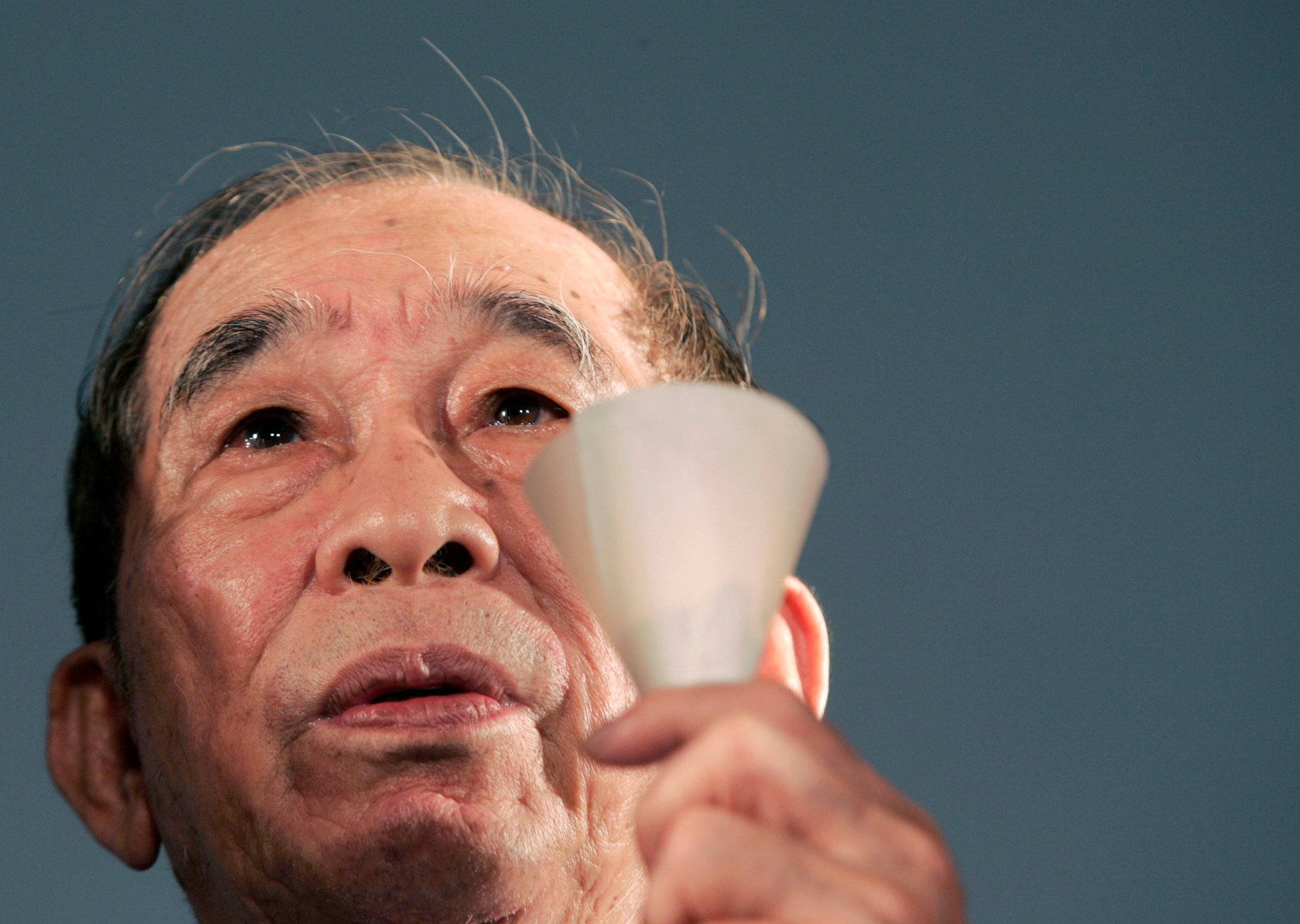

In May that year, the five pan-democrats, including Albert Chan, Leung Kwok-hung, and Wong Yuk-man, won back their seats amid a record low turnout of 17%. They toasted their victory saying 500,000 Hong Kong people had voted to show they cared about democracy. Pro-Beijing figures said the poll was a waste of taxpayer money.

2011

Szeto Wah, a prominent democracy activist in Hong Kong, died from lung cancer at age 79. Szeto was a leftist who had organized protests against the British before the handover, but he cut off all ties to Beijing after the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. In the same year, he founded the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, which holds an annual June 4 candlelight vigil to remember the deaths in the military crackdown to the present day.

2012

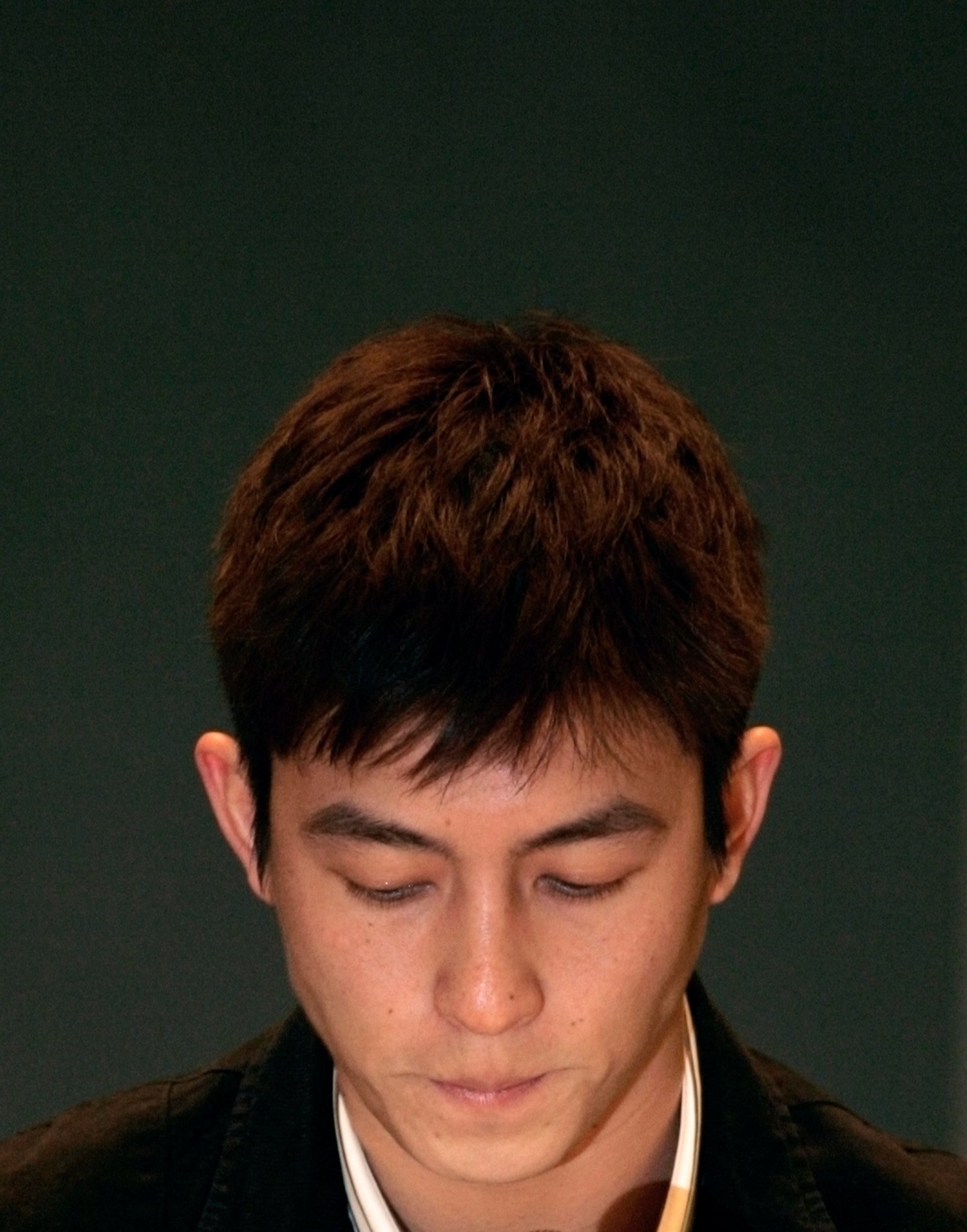

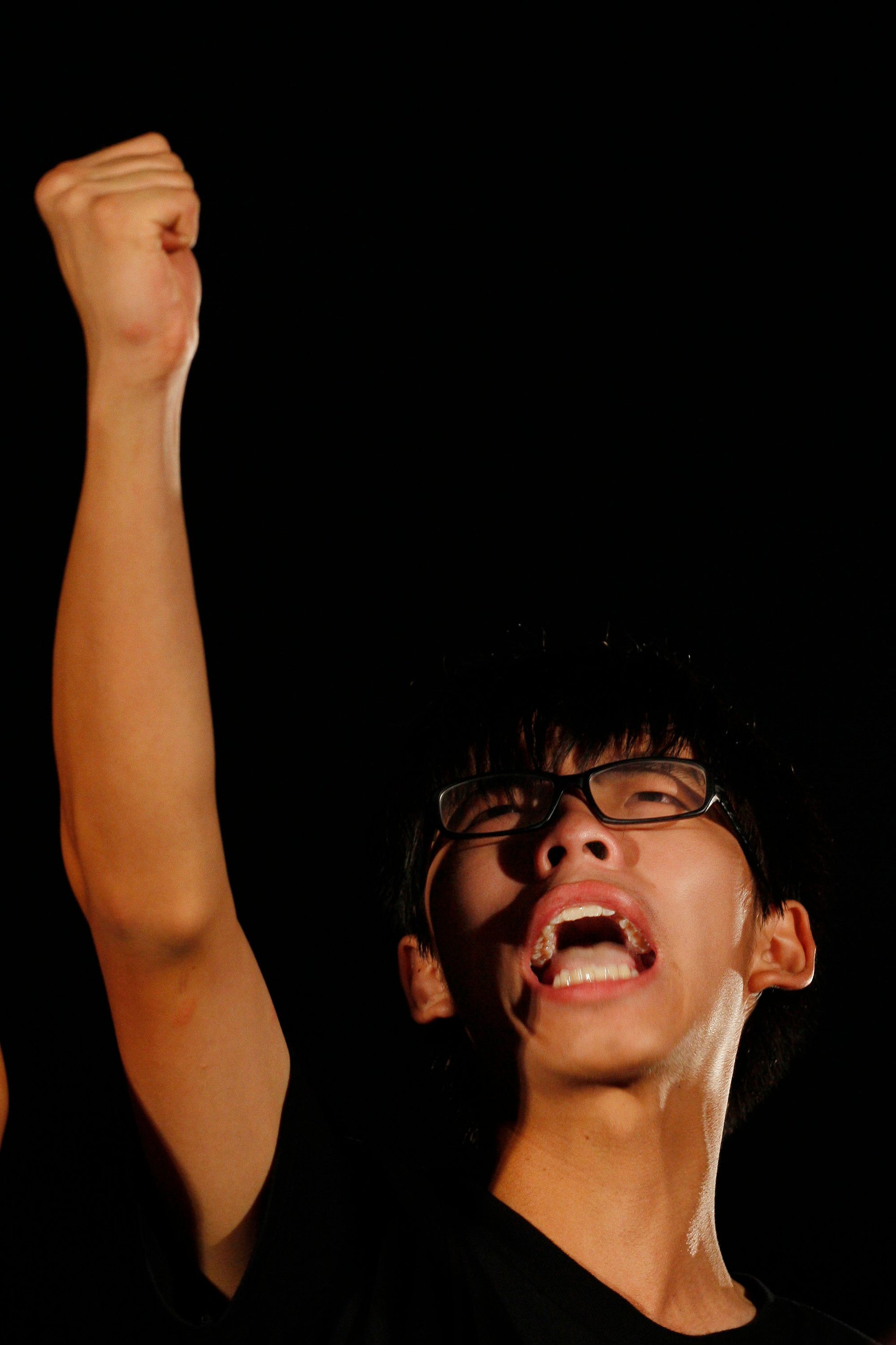

Joshua Wong, now one of Hong Kong’s best-known democracy activists, shot to prominence here when he was still in high school. In 2012, a 14-year-old Wong and his Scholarism activist group became the face of a series of protests against implementing “national education” in Hong Kong, which he and other critics denounced as Chinese patriotic “brainwashing.”

He went on to become one of the leaders of the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement. In 2016 he co-founded a new political party, Demosisto, which advocates a referendum to determine Hong Kong’s sovereignty.

In March that same year, Leung Chun-ying won 689 votes out of the 1,132 votes cast by the largely pro-Beijing election commitee, and started his five years as chief executive. During his term there was a drastic escalation in clashes over Hong Kong’s autonomy and he leaves this month as one of the territory’s most-loathed leaders.

2013

In May 2013, Edward Snowden fled to Hong Kong to leak thousands of classified documents about the US’s spy program. Seven refugees sheltered him in their small, cramped flats for two weeks, before he headed to Moscow, Robert Tibbo, a lawyer for Snowden and the refugees, told reporters in 2016.

The refugees decided to speak out about hiding Snowden to pressure the Hong Kong government into giving them asylum after years of waiting, but their cases were rejected this May. “Now what they’re facing is a transparent injustice from the very people that they asked to protect them,” said Snowden, lashing out at the Hong Kong government’s decision.

2014

In September 2014, tens of thousands of Hong Kong citizens occupied the city’s central financial district and elsewhere demanding universal suffrage to elect the chief executive in 2017 without Beijing pre-screening a shortlist of candidates.

Hong Kong’s biggest protest in decades, the demonstration disrupted the city for 79 days. The umbrella has become a symbol of the movement, used to shield protesters from police tear gas, pepper spray, and batons.

The protest failed to make any perceptible progress toward universal suffrage, but inspired many young people in Hong Kong to devote themselves into politics.

2015

In late 2015, five Hong Kong booksellers mysteriously disappeared one after another, leading many to fear they were abducted by the Chinese government for publishing political titles critical of Beijing. Months later, two of them reappeared to say they traveled to China on their own volition.

Lam Wing Kee, owner of Causeway Bay Books, offered a completely different account. After returning to Hong Kong in June 2016, Lam gave a long press conference to detail his eight-month detention in China, saying he was kidnapped across the border, forced to make a fraudulent public confession, and denied any legal representation.

The bookseller disappearances have raised unprecedented concerns about Beijing’s meddling in Hong Kong’s judicial independence and freedom of publication.

2016

Yau Wai-ching, 25, is the youngest woman to be elected Hong Kong’s legislator. In the swearing-in ceremony in October 2016, Yau used a derogatory term against the Chinese nation in her oath, and was barred from officially entering the legislature. A Hong Kong court later ruled to disqualify Yau and her party colleague Baggio Leung, who took a similar oath using the slur.

The oath-taking saga also prompted Beijing to issue an interpretation of the Basic Law, even before the Hong Kong court could rule, demanding Hong Kong lawmakers and officials swear the scripted oath “correctly, completely, and solemnly.”

2017

Carrie Lam will be sworn in as Hong Kong’s new leader on July 1, at a ceremony presided over by Xi Jinping. Widely seen as Beijing’s favored candidate, Lam won 777 votes out of the less than 1,200 valid votes cast in March’s election, becoming the first woman to hold the position.

Lam, 60, is a career civil servant. She previously served as Hong Kong’s No. 2 official under unpopular outgoing chief executive Leung Chun-ying and campaigned on promises to make housing more affordable and improve education. Upon winning, she said she would heal Hong Kong’s divisions and “unite our society to move forward.”

As Beijing warned against Hong Kong independence in the run-up of the July 1 celebration, Lam recently said that she wants to teach Hong Kong kids “I am Chinese” as early as kindergarten.

Read Quartz’s complete series on the 20th anniversary of the Hong Kong handover.