Germany’s upcoming national election was supposed to be the toughest one yet for Angela Merkel. When the disciplined statesman, who had maintained the trust of her people as chancellor for a decade running, decided to open Germany’s borders in 2015 and let in some one million refugees over the next year, commentators were writing her political obituary. The refugee crisis had, according to some, left the country “as bitterly divided as Donald Trump’s America.” 2017 was pegged as her “year of reckoning.” The chancellor was “weak and vulnerable,” they claimed, and ripe for the picking.

The reality, however, has been far less dramatic.

Across the world, the word often used to describe the upcoming German election on Sept. 24 is “boring.” After 12 continuous years in power, Merkel continues to be a supreme force in German politics. Her Christian Democratic Union, the center-right conservative party, has a 14-point lead ahead of her closest rival, the center-left Social Democrat leader Martin Schulz. When voters were asked who they want to be the next chancellor in the latest infratest-dimap poll in May, the answer was Merkel.

Global politics watchers were consumed by the prospect of right-wing populists sweeping the Dutch and French election. But as those fears have subsided after Brexit and the election of Trump, the German election feels to many like a fait accompli. No candidate has proven to be much of a contender for Merkel—and she knows it. When Merkel kicked off her reelection campaign, she joked: “I almost forgot to say that the election isn’t already decided,” adding, “and of course, we need every vote.”

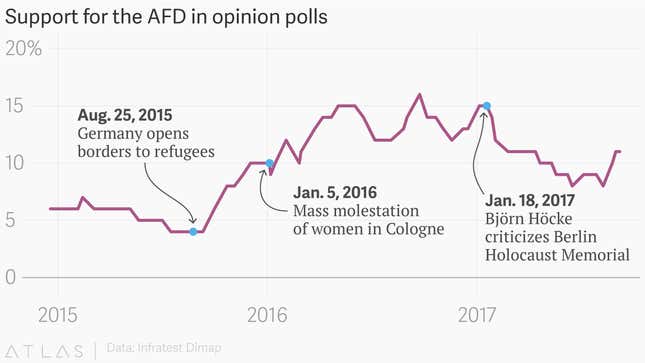

Her confidence is particularly remarkable considering that political conditions heavily favored a populist upset; a large influx of refugees, followed by terrorist attacks, a mass molestation of women at Cologne railway station, and a fearsome debate on national identity. And yet, Alternative für Deutschland (AFD), the populist, anti-immigrant party was polling around 16% last year, a figure that has since dropped to between 9% to 11% recently. Last month, the party was forced to admit that it has an image problem.

The country’s enduring allegiance to Merkel’s moderate leadership is partly a product of her political savvy. Her calm, steady hand in the face of political crises has kept extremists in check. But so has the country’s commitment to remembering and atoning for the tragedies of the Nazi era. The opposition also failed to form an effective populist coalition due to infighting and botched messaging.

The far right’s folly

Political moderation is not a recent phenomenon in Germany. The country’s sense of remembrance and repentance has inoculated it against the sway of far-right populism for decades. Almost all students are required to visit former concentration camps or war documentation centers, with hundreds of holocaust monuments and memorials across the country. Germany still pays millions in reparations to victims of Nazis, and Germans generally bristle at those who try to downplay Germany’s crime. When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu tried to link the holocaust with Muslims in October 2015, for instance, Merkel sharply rebuked him, saying: “We know that responsibility for this crime against humanity is German and very much our own.”

“It’s been almost impossible for a political party in Germany, since the end of the second world war, to occupy a position to the right of the Christian Democratic Union [Merkel’s party],” says Johanna Schuster Craig, assistant professor of German at Michigan State University.

The AFD has, however, tested Germany’s immunity to right-wing populism. The party, founded in 2013 by a group of economists and business leaders bucking the euro zone crisis and the Greek bailout, seized on the refugee crisis to further its cause. Merkel’s conviction that there was no alternative to the Greek bailout, a wobbly stance relative to her hardline finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, riled the nationalist AFD and put the far right party on a war path to prove her wrong.

The party found its moment in the summer of 2015, as the refugee crisis quickly unravelled. In August of that year, Germany became the first European country to free refugees of a bureaucratic “trap.” The Dublin Protocol, enacted in 2003, forced refugees to claim asylum in the first safe country they reach. Merkel swiftly suspended it, allowing refugees who made the perilous journey to Germany to apply for asylum without fear they’d be deported to one of the countries they had passed through. The move gave way to the entry of roughly a million refugees in the space of a year.

The AFD’s next boost came after the mass molestation of women at Cologne railway station in 2016. Between 500 and 1,000 men sexually assaulted women in Cologne on New Year’s Eve in a coordinated attack, reportedly throwing firecrackers into the crowd (link in German) to create chaos before rushing at their victims to violently grope and rob them (link in German). The perpetrators were largely of Arab or of North African descent, according to the city’s police. Anti-immigrant activists claimed the incident as proof of the dangers inherent to Merkel’s refugee policy.

Frauke Petry, then leader of the AFD, glommed onto Europe’s most notorious far-right leaders, who were pushing the message that their time had come. Emboldened by Brexit and the election of Trump, Europe’s far-right leaders descended on Koblenz, Germany for a “European counter-summit.” Among the attendees were Marine Le Pen of France’s National Front, Matteo Salvini of Italy’s Northern League, and Geert Wilders of the Dutch Freedom Party, who declared 2017 to be “the year of the patriotic spring.”

But the party took nationalism too far. While some Germans were frightened by the rapid influx of migrants, others were turned off by the AFD’s extreme rhetoric. During the same week as the European counter-summit, leader of the AFD in the eastern German state of Thuringia, Björn Höcke, slammed the tribute to the murdered Jews of Europe near Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate and called for Germany to finally stop atoning for its past.

“They wanted to cut off our roots and with the re-education that began in 1945, they nearly managed,” Höcke told a crowd in Dresden. “Until now, our mental state continues to be that of a totally defeated people. We Germans are the only people in the world that have planted a monument of shame in the heart of their capital,” he added.

It was a dramatic break from Germany’s post-war consensus, which emphasizes understanding and taking responsibility for the horrors that occurred. Immediately after, the AFD began sliding down in the polls, sparking ugly party infighting. Party leader Petry immediately distanced herself from Hocke, saying “with his unauthorized solo actions and constant crossfire, Björn Höcke has become a burden for the party.” Her sentiments were echoed by Marcus Pretzell, AFD leader in the western German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, who insisted that Hocke didn’t represent the AFD.

Meanwhile, Merkel carefully paired her humanitarian convictions with practical limits, making clear that opening the country’s borders was an extraordinary gesture that wouldn’t continue. In January 2016, Germany tightened asylum laws, preventing refugees from bringing their families to join them for two years. In March of that year, Merkel helped secure a deal with Turkey to stem the flow of refugees, offering Turkey aid money in exchange for taking back migrants who’s crossed through its territory. By April, the number of migrants arriving in Greece (the main route of Syrian refugees was through Turkey, Greece, and then to elsewhere in Europe) dropped by a staggering 90% from the previous month. Merkel also pushed for refugees to be distributed more equally across Europe and bolstered the EU’s external borders.

Her statecraft paid off. In 2016, Germany saw a 69% drop in migrants from the previous year. Merkel spent the spring of 2017 visiting North African countries to address the root of the crisis. By June 2017, support for the AFD had dwindled to 8%.

Merkel’s popularity, meanwhile, rose from its trough of 45% in September 2016 to 63% a year later. She maintains a sense of pride for Germany’s humanitarian gesture towards refugees, while stressing that “what happened in 2015 cannot, should not and must not happen again.” In doing so, Merkel has kept conservative voters on board, whilst reassuring liberals that she remains a bastion of tolerance.

A fragile coalition

Far-right populism requires a tenuous combination of voters: conservatives, disaffected workers, and extremists. (See the rise of Brexit and Trump, neither of which were rooted solely in white working class discontent, but instead on a combination of workers and wealthy professionals.) Attracting such disparate groups demands the deft of an extremely charismatic leader.

“These coalitions we saw in Brexit and Trump is very difficult to maintain in Germany,” says Sergi Pardos-Prado, an associate professor at the University of Oxford and expert on migration and public attitudes. The AFD targets both the educated, conservative, free-market loving Germans who live in the west, as well as the disaffected working class in eastern Germany. But the policies that benefit one side—such as loosening of labor laws—don’t necessarily benefit the other. Nor does the rhetoric apply to both; calling a holocaust memorial a “monument of shame” is a waste of breath for moderates focused on the economy.

“It’s difficult to unite these two souls of the party. Unless you have a very clever, very charismatic leader, and a very clever narrative,” Pardos-Prado says.

Germany’s economic stability in the face of globalization hasn’t helped. Most Germans favor globalization, and it’s not hard to see why. Unemployment remains low (particularly youth unemployment), unions have successfully fought for higher pay and better working conditions, and though income inequality exists, it has been narrowing over the last five years. Germany has shielded its workforce against globalization’s downsides with apprenticeships that train highly skilled workers outside university and embed them with companies. By contrast, non-university workers in the US were far more likely to lose their jobs in the aftermath of the global recession.

Job security across classes makes the populist message a harder sell, according to Pardos-Prado, because there’s no “clear constituency in Germany that should necessarily, suddenly become anti-immigrant.”

Steady as she goes

Merkel’s unflappable public face has been a calming force for Germans in the wake of the refugee crisis and terrorist attacks that followed.

Other regional powers haven’t fared as well. At the height of the refugee crisis in 2015, former UK prime minister David Cameron caused a stir by referring to migrants as “a swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean, seeking a better life, wanting to come to Britain because Britain has got jobs, it’s got a growing economy.” He was roundly criticized by human rights groups for using dehumanizing language, and setting a bad example. Right-wing media followed suit (columnist Katie Hopkins, for example, referred to migrants as “cockroaches.”)

Merkel, by contrast, has called on MPs to avoid the dehumanizing language of right-wing populists. In 2016 speech to German lawmakers, Merkel said that taking cheap shots at each other would, ultimately, help “those who rely on slogans and simplistic answers.” But if MPs stick to the facts, “we will win back the most important thing: people’s trust,” she said.

Following the terrorist attack at a Berlin Christmas market in 2016, Merkel defended her decision to suspend the Dublin protocol and let refugees flow into the country, calling on Germans (paywall) to counter the militants’ “hatred” with “humanity.” She used her New Year’s address (paywall) to slam the anti-immigrant movement.

Her moral rectitude has stuck with German voters. A majority of Germans reject a link between Merkel’s immigration policy and the terrorist attack in Berlin, according to Forsa’s survey. A 2017 survey showed there was little change since 2015 in public opinion towards refugees, with most still eager to support and welcome refugees (in a separate 2017 survey, 57% of respondents said Germany can handle the refugee influx, up from 37% the year before). By contrast, the UK public has high levels of opposition to immigration and hardening attitudes towards refugees.

Britain’s efforts to take in migrants pale in comparison to Germany. Cameron committed to the UK taking 20,000 Syrian refugees from refugee camps in 2015, but the government has resettled just over 6,000 refugees. The government had also committed to resettling 3,000 child migrants scattered in unofficial refugee camps in Europe, but prime minister Theresa May reduced that figure just 350 in February.

If there’s a lesson from Germany’s experience, it’s that a country can learn the way forward from its own history, when the leadership is right.