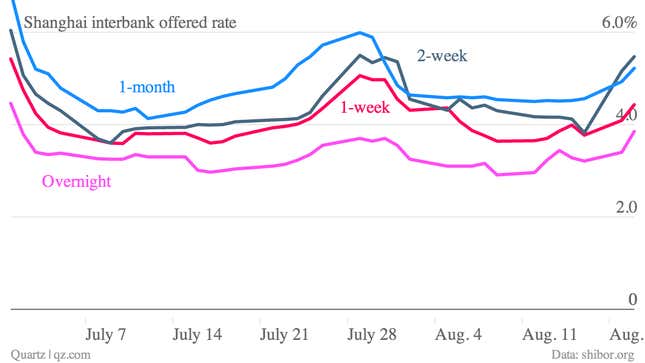

The supply of cash in China’s banking system is getting tighter. Yesterday, the 14-day bond repurchase rate on Shanghai’s interbank market—known as “Shibor,” it reflects rates banks pay to borrow from each other—jumped 133 basis points, to 5.16%. Today, the 14-day rate climbed to 5.61%, a seven-week high, before settling to 5.47% at market close.

Rates are rising because banks are clamping down on lending to each other in anticipation of the end of the month, when they must have sufficient deposits on hand to meet reserves required by the government. That money tends to come from maturing wealth management products (WMPs), the financial products banks have been using to offer retail investors high yields while keeping loans off their balance sheets. (These products tend to offer high rates because they’re funding risky projects, which is precisely why banks want to keep them off their books.)

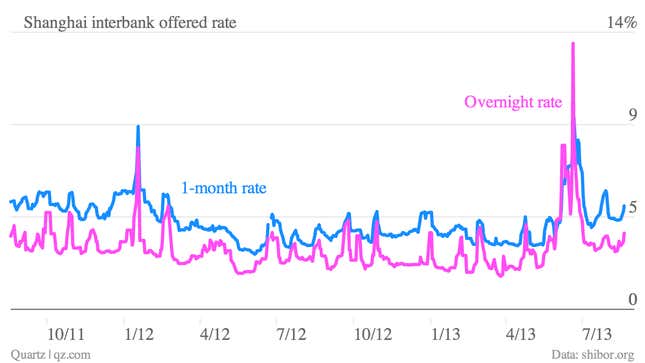

As you can see, rates pretty much always spike at the end of the month:

But those spikes are fairly normal. What isn’t normal is the rate explosion that happened in June, when a perfect storm of tightening money supply caused a liquidity crisis. Toward the end of that month, interbank rates leapt well above 8-9%, the level at which financial markets tend to stop functioning.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the country’s central bank, needs to avoid a reprise of that episode. But it’s clearly feeling jittery about whether it can. Earlier today, it pumped 36 billion yuan ($5.9 billion) into the open market via one-week repurchase operations, a jump of more than 200% from the amount injected just a week ago.

Climbing rates signal the move won’t do the trick. “Even though the amount [of reverse repos] is rising [compared to last week], it is still not enough to ease market worries,” a dealer at a city commercial bank in Shanghai told Reuters. “Money rates should hover around high levels in the near term.”

The persistently high rates suggest that banks aren’t lending much to one another despite the PBOC’s amped up cash injections. What’s more, banks are likely having a much harder time gathering the cash they need by month’s end than their (fairly healthy) balance sheets would suggest.