Can an AI-powered bot help parents raise better humans?

There is no shortage of advice on how to raise kids today. Books, magazines, and websites offer tips on everything from managing kids’ sleep and diet to navigating friendships and screen time. But the parenting advice of the future may look a lot more like Muse—an AI-powered app that aims to use machine learning and big data to try and help parents raise creative, motivated, emotionally intelligent kids.

There is no shortage of advice on how to raise kids today. Books, magazines, and websites offer tips on everything from managing kids’ sleep and diet to navigating friendships and screen time. But the parenting advice of the future may look a lot more like Muse—an AI-powered app that aims to use machine learning and big data to try and help parents raise creative, motivated, emotionally intelligent kids.

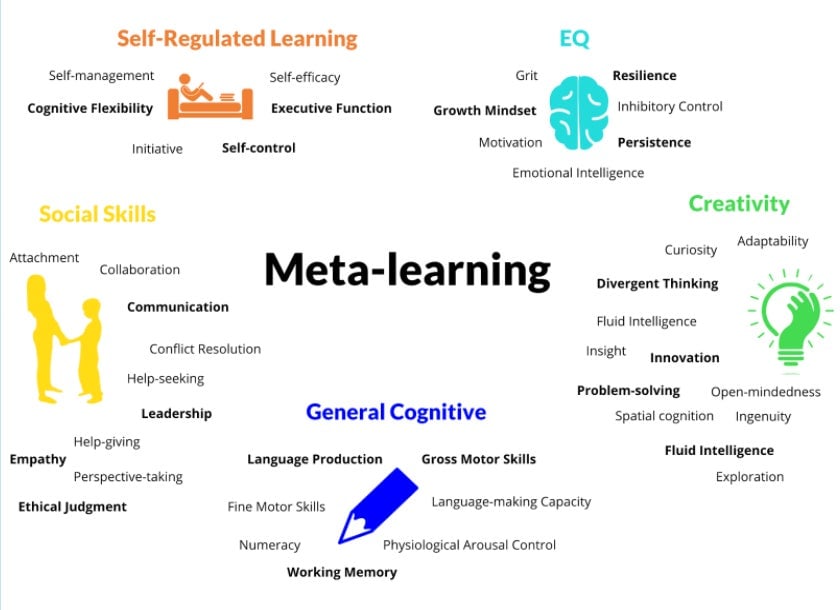

According to Vivienne Ming, a theoretical neuroscientist and entrepreneur who created Muse with her wife, Norma, in 2016, parents ask themselves the same question every day: “What can I do right now to best help my child?” Muse is an attempt to answer that question, offering parents activities tailored to their individual children that are geared toward developing 50 skills, from growth mindset to metacognition, problem-solving, and working memory. It is not tech for kids, but tech for parents to help inform how to raise their kids.

If it sounds like yet another product that promises to turn kids into tiny, data-optimized geniuses, Muse says it has its sights set on a different goal. Rather than focusing on cognitive skills like math and literacy, the app attempts to aid parents in developing the traits that actually predict better life outcomes, such as self-control, long-term persistence, and emotional regulation.

“My purpose is building better human beings,” Ming says. By ‘better’ she does not mean kids who are a shoo-in for Harvard or more ready to code at age three, but children who are more self-actualized. The project’s ambitions raise a perplexing question for the digital age: Can technology help parents teach their kids to be more human?

Inside Muse

Muse, which can be delivered via app or text, currently costs $5 per month per family in Europe and the US (the next version will be free to all parents). It asks parents one question every day: Have you and Lucas visited a library in the past month? Does Maria attend school outside of the home? Parents’ responses are fed to the AI along with unstructured data; parents might record snippets of audio or video conversation with their child, or upload photos of a toddler’s finger-painting.

Those responses help the app create a constantly evolving profile of each child that attempts to measure not just their static ability at one moment in time, but their developmental growth. The machine learning constantly searches for the best question to ask parents about their child, and the best activity to suggest that might help the child improve on areas of weakness. The daily questions also incorporate traditional survey-type assessments, such as questions relating to empathy or metacognition. By using both old-school survey type questions and naturalistic data, the AI learns how the two relate.

Muse is small: it currently has about 2,700 users: 55% in the US, 27% in Germany, and 13% in other locations around the world.

Unsurprisingly, the biggest query Ming receives from parents is about how their kid scores on a certain trait—say, divergent thinking. But Muse doesn’t share that information: The point of the app is improvement, not evaluation. The number-one piece of advice Muse got from experts including Angela Duckworth, an authority on grit, is that as soon as you tell a child they have a trait, or lack one, their abilities become fixed in their mind and less malleable.

Muse will include visualization of kids’ growth in the next version, Ming says. That said, “‘How does my child compare to others?’ is a question I won’t answer because it only hurts, largely by inducing fixed expectations in the parents,” she says.

Instead, the Mings are focused on a different problem. They say that right now, education measures whether children can acquire and regurgitate specific content knowledge. While grades and test scores are our current proxies for success, research shows success tends to be more closely aligned with things like conscientiousness, resilience, and emotional regulation. “What matters more than a particular body of knowledge is the ability to learn whatever knowledge is needed and to deploy that knowledge productively,” they write in a white paper (pdf). They dub that ability meta-learning. The 50 developmental traits that Muse is designed to build coalesce around building children’s meta-learning abilities.

“We can see a rich, real human being grow and develop in time, and understand that and then ideally leverage that – that unique child – in our recommendation of things to do,” Ming says.

The privacy problem

Technology that collects data about children is, of course, a hornet’s nest of data and privacy concerns—not to mention fears about allowing tech to serve a central role in children’s upbringing. In October 2017, Mattel pulled the plug on Aristotle, a smart device aimed at kids from infancy to adolescence. Mattel said the first-of-its-kinds WiFi-connected device was meant to “comfort, entertain, teach, and assist during each development state — evolving with a child as their needs change.”

But critics said the AI-fueled device raised serious concerns about privacy, children’s development, and the crucial bond between parents and children.

Sherry Turkle, director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self and author of the book Reclaiming Conversation, told the New York Times that “intimate machines” like Aristotle could change “the ground rules of how people think about personhood.”

“We can’t put children in this position of pretend empathy and then expect that children will know what empathy is,” she said. “Or give them pretend as-if relationships, and then think that we’ll have children who know what relationships are.” This was not an anti-technology stance, she argued, but simply an argument against technology that pretended to do things it could not.

“Trust us”

Ming is aware of these potential criticisms. She says Muse is a philanthropic venture, which has taken no venture funding and no advertising dollars, and has no plans to do so. Parents own their children’s data and can get it back whenever they want, although they cannot untangle the fact that the data is used to train the app’s AI. “It’s your data, it’s not ours,” Ming says. “We can’t do anything with it but power Muse.” They do not share the data with other companies or organizations, she says.

But Ming is open about the shortcomings of her pitch. “It boils down to, do you believe us? We could be doing bad things.”

Another concern is what kind of bias might be trained into the data: Could machine learning lead the app to embed gender or racial biases? The World Economic Forum recently published a report on preventing such discriminatory outcomes in machine learning, including recommendations on active inclusion and fairness. Ming says bias is a “huge issue,” and it is not something she takes lightly.

Still, she admits, “thinking that it’s solved just because I have good intentions is a trap.” Muse is attempting to address the potential for bias in two ways. First, employees dig into the research that underpins the AI to see how the results pan out among different demographics and cultures—for example, does grit have the same effect on all kids? Second, Muse is designed to err on the side of caution with its recommendations until it “knows” the child better. “Muse doesn’t recommend an activity as a best guess,” Ming says. “It recommends the activity that it is most confident will make a difference.”

Finally, there is the question of how relying on a bot may affect the way adults develop as parents. Will we act naturally doing the activities Muse tells us to do, even if they don’t feel natural? Parenting is a lifetime trial-and-error experiment. Will computer-adapted parenting detract from the way most of us learn to do it—messing it up one day at a time?

Context matters

Ming is not your typical Silicon Valley technologist. Friends say she is remarkably uninterested in making big money. What motivates her is understanding differences between people, and designing technology that can help them make improvements.

This drive comes from a personal place. She is transgender, and witnessed firsthand how differently people treated her after transitioning in her 30s. Prior to her transition, students asked her tons of questions; afterward, less so.

“We are bad at valuing other people and we are worse the more different they are than us,” Ming told Quartz at “Pride and Prejudice,” The Economist’s LGBT conference in London, in 2016.

Much of her previous work before Muse focused on developing holistic approaches to assessing people’s abilities. As chief scientific officer at Gild, a workforce-science company, Ming and her team tried to deconstruct the qualities of a successful programmer, assessing whether a programmer’s code got reused, how other programmers rated it, and other variables. The goal was to understand whether the best companies hired the best people, or just the ones with the best degrees. She also looked at advancement opportunities after a worker got a job—what it took for a woman, for example, to have the same chance of promotion as a man who produced the work of the same quality.

“I don’t build AI,” she told Quartz. “I make glasses to correct people’s vision … so to see everyone clearly.”

Other research underscores this commitment. Before Muse, she attempted to to see if AI could predict student outcomes on tests through their interactions, putting microphones in college and MBA classrooms to listen to students’ conversations and following students’ online discussions. She says her AI model could accurately predict students’ final letter grade in class, as well as get within 2 points of their 100-point final grade. The goal was to prove that high-stakes tests were unnecessary, and that teachers could use other, better tools to assess their students’ understanding of course material.

Both her work at Gild and in classrooms focused on building prediction models for performance. But Ming felt constrained by that. She wanted to figure out how to use AI to improve the skills we need, not predict the ones we don’t.

Are we ready for this?

There is ample evidence that we can modify parents’ behavior through technological nudges. The texting service Text4Baby, for example, sends messages to pregnant women and caregivers with reminders about doctor visits and providing important health information. Vroom, an app for building babies’ brains, also offers research-based prompts to parents to help build positive relationships with their children and increase so-called “serve and return” interactions—those which encourage bond-building activities like singing, talking and reading (among others). These messaging technologies have been shown to have positive effects.

Jordan Shapiro, a professor of philosophy at Temple University and author of the forthcoming The New Childhood: How Kids Will Need to Live, Learn, and Love in a Connected World, says the much harder question is what exactly Muse is measuring.

It’s not as simple as asking whether an app like this is good, he says. The app needs to understand which developmental milestones are objective, and which are context-dependent. He uses empathy as an example. Muse measures the expression or articulation of empathy, the measurement of which is dependent on big things like language, and on practical factors like how it is recorded, whether via pencils or computers.

“There’s no doubt we are moving toward more AI solutions,” Shapiro says. “We need to have the conversation so that it happens on our terms as people, and not on the machines’ terms.” If we don’t think about the values we program into the AI solutions, we “limit our understanding of human development to what’s AI-able.”

Moving forward

Some child development experts see huge potential in the tailored suggestions offered by Muse, arguing that many parent programs, especially those offered at scale, can suffer because they are one-size-fits-all. Research shows that behaviors like talking, singing, and reading to infants and young children are critical to building babies’ brains; Muse could help more parents learn to do that.

Though it seems geared in many ways for overly-ambitious, well-off parents, Ming is eager to get it to more disadvantaged populations who potentially could benefit from it. She is already working with nonprofits in India, China, and South Africa to produce free versions for poor and rural populations. Could AI-generated parent coaching help disrupt the strong connection between socioeconomic background and student outcomes? Ming thinks so.

“Every one of the 50 [traits] is something you can change about somebody,” she says.

But the app needs more users to improve its machine learning, which presents its own set of thorny issues. If an education ministry attempted to use Muse to develop a parenting app, who would own that data? Could a country use Muse data to sort children into schools, or into future jobs? The data could be ugly in the hands of a government more interested in building a specialized workforce than say, developing the arc of human potential. And data privacy conversations still have a ways to go. “It may be 10 years ahead of its time,” says one early childhood expert who is familiar Muse but is not authorized to speak to the press.

More evidence is needed to prove that Muse can actually do what it says. Socos Learning, the education company founded by Ming that develops Muse, is testing the effectiveness of the app, asking kids to take more traditional assessments of the 50 developmental traits to see if the AI is accurate.

Whatever the future of Muse, it’s already sparking important conversations. At present, the question of how technology affects children tends to focus on a one-dimensional issue: Do kids spend too much time on screens? That ignores a separate, crucial question: How can technology be used to help parents help their children?

“We are doing mad science,” Ming admits. It’s the kind of mad science that could create miniature mad scientists—or simply help parents raise happier human beings.

This reporting is part of a series supported by a grant from the Bernard van Leer Foundation.