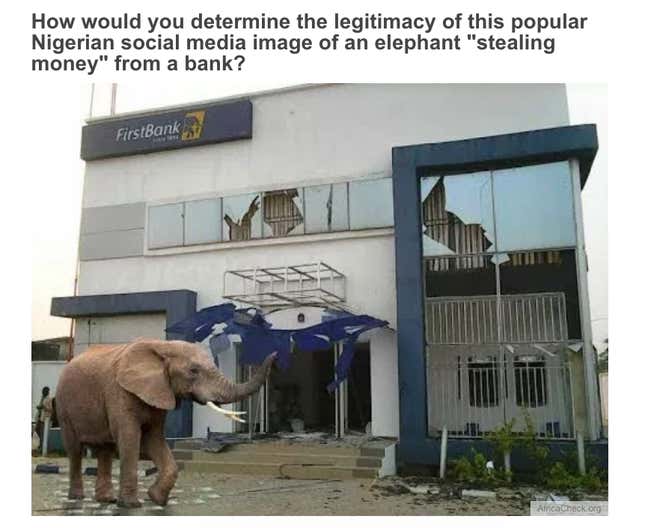

It’s a quiz consisting of 16 questions, querying takers on how to spot fake news or identify unreliable partisan clickbait. Did a Kenyan man drive a tanker to create an artificial watering hole for wild animals? Did another in Kenya’s Rift Valley region pay dowry with bitcoin instead of cash and cows? Or did an elephant steal $400,000 from a Nigerian bank?

All, you guessed—or not— are true stories, except for the large mammal leading a bank heist.

The string of questions was collected from both true and false stories circulating online in Kenya and Nigeria by the digital research company Nendo. The quiz was built as part of a larger US government program aimed at fighting fake news in Kenya, known as “Stop. Reflect. Verify.” In collaboration with the signature US State Dept initiative for young African leaders, the program hopes to prevent misinformation and urge users to independently verify the validity of sources and news before sharing on social media.

The media literacy campaign comes as deliberate attempts to disseminate false or misleading stories have seeped not only into the political and diplomatic landscape in Kenya but also into the news cycle and the corporate world. During the 2017 polls, 90% of Kenyans had heard or seen fake news stories related to the election, with a cross-section of the population using popular apps like WhatsApp and Facebook to spread misinformation.

While there’s no easy answer in sight, local startups and digital strategists including Nendo have been trying to figure out how to help clients and companies deal with fake news. That’s why the US embassy in Nairobi, itself a target of fake news, kickstarted the year-long project in Kenya, which will mix the online quiz with educational videos and public outreach.

Mark Kaigwa, the founder of Nendo, says that in devising the quiz, they wanted it to be interactive as much as it was informational. For every question answered, quiz takers are informed about becoming critical news consumers including how to review domain addresses to spot fake ones, noting the poor grammar or spelling errors in stories as a sign of their falsity, how to reverse search images, and the various ways in which popular brands are often used to spread websites that contain malicious software.

“Quizzes are among the web’s most engaging type of content,” Kaigwa told Quartz. “Quizzes tend to have a very strong metric around getting people to share them, especially when there’s some kind of reveal.”

Dissonant move

When the #StopReflectVerify program launched in March, US ambassador to Kenya Robert Godec said fake news was “undermining democracy in Kenya” and that to stop it required a “strong collaboration between the media and the public.”

Yet the US involvement was incongruous with president Trump’s own stances, who questioned former president Barack Obama’s birthplace for years without evidence, threw doubt on the accuracy of stories in US media outlets, and even doled out “fake news awards” in January to reputable news companies including the New York Times and Washington Post. Fake news was also a key issue in the 2016 vote, with special counsel Robert Mueller indicting 13 Russians in February for using bogus social media accounts to interfere in the election process.

Facebook, the largest social media player and the leading news source for many Americans, has struggled to curb the spread of fake news on its service despite repeated pledges to do so over the last few years and most recently at US congress hearings with Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg.

Despite the US inconsistency on the issue of fake news, there’s no denying the sophisticated nature of propaganda in Kenya, and the urgent need to educate the public. This is especially critical in a country with high internet speeds, and where almost 90% of the population has access to a mobile phone. Local efforts to tackle misinformation are also crucial in the wake of revelations on how data firm Cambridge Analytica ‘staged’ polls in Kenya where over 100 people died in post-election violence.

Nendo says the next step of the quiz will involve expanding the “question bank,” translating it to French and Portuguese, assessing how people are interacting with it, and spreading it across Africa through various digital platforms. One key event they are targeting is the upcoming Nigerian elections in 2019, where fake news is already a concern.

“The bigger view is media literacy,” Kaigwa said, and “the work starts now.”