Seoul, South Korea

Long before #MeToo took off, three South Korean teachers knew the country had a gender problem.

As recently as 2015, South Korea’s nationwide sex education curriculum blamed sexual violence in part on women not paying for dates, and made a point of highlighting the fact that men have “natural” sexual desires to appease. K-pop stars and other celebrities who own up to being feminists are trolled viciously by male fans. Earlier this year, a kindergarten wrote in a newsletter addressed to parents that a “good wife” should “sexually satisfy” her husband, and that she should be “clean and attractive.” (After a screenshot of the list went viral, the kindergarten apologized.)

For the teachers, Shin Yeon-jeong, Roh Ha-yeon, and Lee Su-Ji, the watershed moment was the May 2016 murder of a woman by a man who had professed misogynistic views, in a public bathroom outside a subway station in Seoul’s glamorous Gangnam district. A year later, the women, trained sex educators who had been working for the Red Cross, struck out on their own to form sex education provider Lala School.

It’s not exactly a friendly environment for those working to rectify some of the country’s startling gender inequalities. But thanks to the explosion of the #MeToo movement in Korea—which has taken down powerful political and cultural figures with a speed and ferociousness unseen elsewhere in the region—demand for better sex education is growing.

That interest is drawing attention to the widespread misperceptions and ignorance when it comes to sex. Many adult Koreans aren’t familiar with basic practices such as how to put on a condom, or what methods effectively prevent pregnancy, educators say—let alone more nuanced understandings of what constitutes harassment or a healthy marital sex life.

Sex education in a former brothel

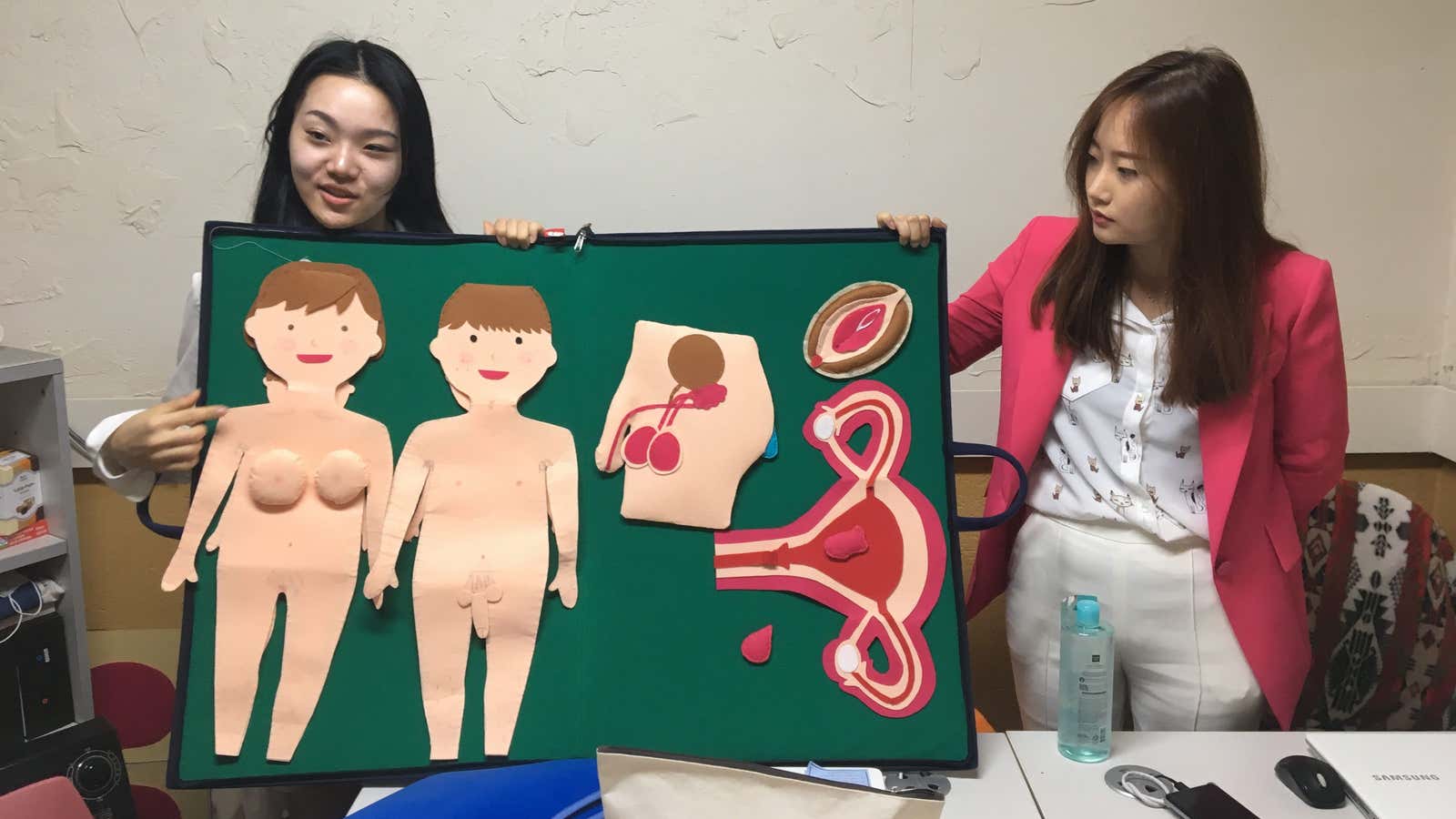

The drab basement in a poor district of western Seoul where the Lala School set up shop used to be a brothel. There the women, all in their 20s, prepare for upcoming classes using a range of props and teaching materials, including banners made from felt depicting human bodies and genitalia in great detail, right down to the clitoris. The messy and run-down space was provided to them by the district government, part of a symbolic effort to shed the neighborhood’s seedy past. The bathroom, which once served the brothel’s clients, only contains urinals, so the women need to walk up two floors to use the bathroom.

Their work often takes them to schools around the district, following an education ministry request this year that schools increase the amount of time devoted to sex education in the wake of #MeToo. A spokesman for the education ministry said that sexual assault cases reported to schools in nationwide rose from 878 in 2013 to 2,837 in 2016. In response, the ministry last August set up a task force to address sexual assault in schools, as well as a call center for people who want to directly report sexual harassment in schools to the government.

Shin (a fan of La La Land, the movie that partially inspired the group’s name because it alludes to a utopian place) says the core of the group’s mission is to correct the gender inequality inherent in the way sex education is taught in Korean schools. This is manifest in a number ways, said Shin, including putting the onus on women to prevent harassment—for example by advising students not to hang out alone with friends of another gender. Schools also promote the idea that women should be “clean” and “virginal,” at the expense of education about women’s sexual desires.

“I try to tell (the students) that women also have sexual urges, and that it’s OK to enjoy sex,” said Shin. “It’s not our responsibility to pleasure men.”

Sexual education providers and advocacy groups say that some of the teachings from the 2015 curriculum which blame sexual violence on women remain in place, despite the election of a more progressive government in Seoul in 2017—one that has vowed repeatedly to take seriously the issue of gender inequality and sexual assault.

Adult learning

It isn’t only Korean kids who are getting an education on sex.

Lala School said that since #MeToo took off, it has been fielding more requests from parents on how to talk to their children about the movement. Many realize they themselves received inadequate sex education, and they need advice on how to talk to their kids about human anatomy, and how babies are made.

In addition to its work with children, Lala School also conducts regular ”Sex Salons” for adults, where for a fee, people come to learn about a range of issues relating to sex. Props used by the women in their classes include polystyrene models of penises to demonstrate how to properly put on a condom.

Many people still think that the withdrawal method is effective at preventing pregnancy, said Kim Tae-gun, a 35-year-old freelance sex-education teacher in the southern city of Daegu whose customers are mostly university students. Kim, whose blog (link in Korean), Sex Education Because We Are Human, publishes questions about intercourse from readers and features videos of him explaining things related to sex, said that demand for his services has increased since the #MeToo movement kicked off in Korea. (In the video below, he explains that condoms have expiry dates.)

Lee Chun Yu-ran, a 30-something office worker in Seoul, attended a “menopause party” with her mother organized by Lala School in December, and has also been to one of the group’s Sex Salons at the recommendation of a friend. “[Lala School] helped me get out of the twisted reality that Korean woman cannot enjoy sex as part of a healthy life, and to recognize the need for gender equality,” said Lee Chun. “I learned that there can be 100 different kinds of sex for 100 different people.”

The F-word

Yet many sex educators say that despite the flourishing of interest in sex and gender issues in Korea, one thing still remains taboo—feminism.

“Many parents agree on [the importance of] gender equality, but have a negative opinion about the word ‘feminism,'” said Kim Bo-gyeong, 27, who teaches fourth-graders at a school in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi province. “So I just teach the content without using the word ‘feminism’ to avoid complaints.” The school recently held a “gender equality week.”

The aversion to mentioning feminism in conversations about gender in Korean classrooms is reflected more broadly in Korean society, with K-pop stars who profess sympathy for the feminism subjected to bitter criticism from male fans. As in the US, the phenomenon is particularly pronounced in the gaming world, with male gamers monitoring the social media activity of female employees at gaming companies for signs of feminist leanings. Feminists are routinely derided as “femi-nazis” or “gol-femi,” an internet term that roughly translates as “idiot.”

Whether the fight for gender equality in Korea is labeled “feminist” or not, #MeToo seems to have inspired women (and men) to express their anger and demands for change. In recent months, tens of thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest against spy cams, the criminalization of abortion, and oppressive beauty standards.

For some, the outpouring of civic participation around women’s rights is reminiscent of the kind of mass movement that transformed Korea first into a democracy, and more recently, brought down a deeply corrupt president. It’s a way they say, to deepen the country’s democracy, by making it more just.

“This society has a lot of injustices when it comes to gender equality,” said Go Young-ju, a 44-year-old English teacher in Iksan, in the southwest of the country. He has been incorporating more feminist material into his classes, such as asking his students to translate Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists from English into Korean. “We all need to find the courage to… take action. My teaching is just the beginning.”

Go said that he sometimes gets calls from other teachers and parents over his feminist curriculum, but he said he’s not fazed. “When we experienced the process of democratization in this country, it was to break down the power structures that were in place,” he said. “It’s worth teaching feminism in order to make Korea a [more] democratic country.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.