Kim Jong-hwan fought along the river near his hometown of Daegu, South Korea, in 1950 to protect a crucial southern port from falling to the North. Sal Scarlato from Brooklyn was just 19 and newly enlisted in the Marines when he sailed in 1952 to join the war against Communism, smoking Lucky Strikes on the way over. Luo Danhong, of Shanghai, with half a dozen years of fighting in China already under his belt, went to supply North Korea’s frontlines later that same year. Kim Seong-yeol dropped out of school in Seoul to fight on the border.

Then young men, or even teens, Korean War veterans are now in their 80s and 90s—and they still don’t know how or when the war they fought nearly seven decades ago will officially end.

The Korean War started before dawn on June 25, 1950, when 90,000 North Korean soldiers (pdf, p. 19) began crossing the 38th parallel into the South. The line had been drawn in 1945 to divide Korea between its “trustees,” the Soviet Union and the United States, after World War II. Soon after the invasion, the US, and then a United Nations force, were fighting to support South Korea. China would later dispatch hundreds of thousands of soldiers to aid North Korea.

The armistice agreement signed three years later didn’t end the war. It only called a truce.

At a summit in April, South Korean president Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un vowed to work with the US to bring an end to the “current unnatural state of armistice,” calling it a “historical mission that must not be delayed any further.” That summit paved the way for the meeting tomorrow (June 12) in Singapore between US president Donald Trump and Kim—the first between sitting leaders of the two countries, which never established diplomatic ties.

For Korean War veterans, the high-stakes—and highly dramatic—diplomacy that is now unfolding could be their last chance to witness a formal end to the war.

The first hot war of the Cold War

“The war lasted 1,129 days,” says Kim Jong-hwan, 87, a quiet man who smiles often and can recite war statistics from memory. “I was in the army for three years, 11 months, and 14 days.”

Three days after Kim Il Sung—Kim Jong Un’s grandfather—gave the order to invade the South, North Korean forces were in Seoul. The capital saw house-to-house combat. Families in Seoul hunkered down in their homes—young men who were spotted were in danger of being beaten, killed, or forcefully conscripted to the other side, according to official and personal war accounts.

Kim Seong-yeol, from Seoul, then in school, quickly joined the outnumbered, and outgunned, South Korean troops. “At that time, students carried guns and knives to contribute to the war effort,” remembers the 87-year-old, who proudly wears a South Korean and US flag lapel pin.

Less than 10 days after Seoul fell, the UN called on its members to assist South Korea, with the US military to lead the UN forces under the command of general Douglas MacArthur. Soldiers from more than 20 nations, including Colombia, Ethiopia, France, Greece, India, and Turkey, joined the effort.

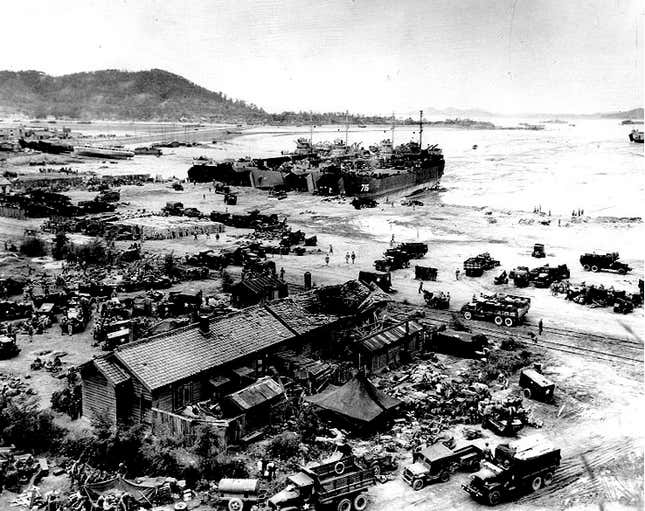

In the first months of the war, Kim Jong-hwan fought along the Naktong River—part of the “Pusan perimeter”—a central point in an allied effort to stop the North Koreans from getting to a southern port where desperately needed supplies and reinforcements were arriving. He says he never thought of himself or his family in those days—and was ready to die at any moment. Kim Seong-yeol, meanwhile, fought at Chuncheon, close to the dividing line.

The tide turned in their favor after MacArthur’s Incheon landing, an assault behind enemy lines on South Korea’s west coast. UN forces retook Seoul in September 1950 and some soldiers began hoping the war could be over by Christmas. But, as American forces approached its borders, China sent in waves of “volunteers” to fight at the side of the North Koreans, mounting a major offensive in October, and stretching the war out another grueling three years.

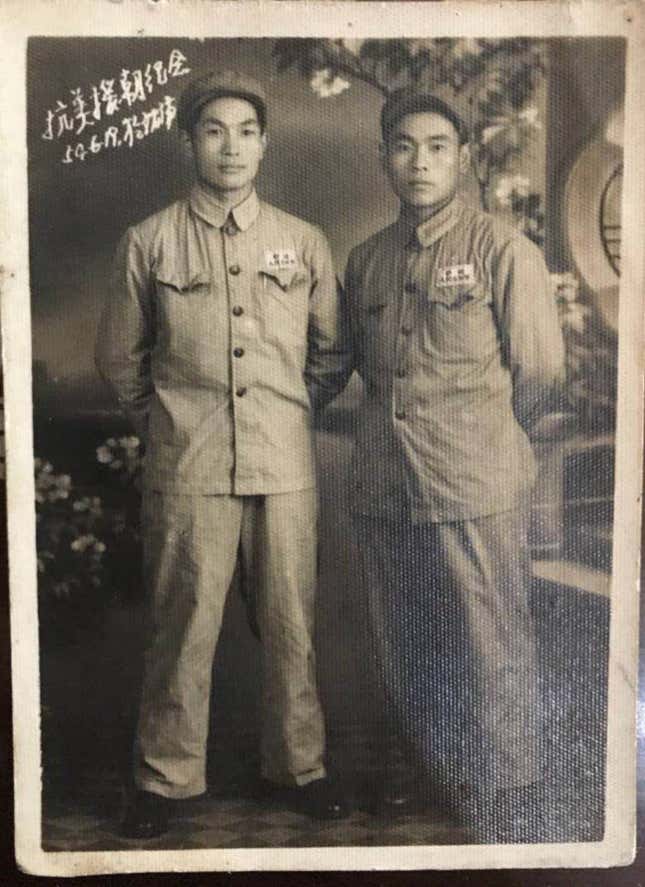

China’s War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea

From a hospital for elderly Communist party members in Shanghai, 94-year-old Luo recalls mostly hearing American planes and encountering American soldiers during the war, not Koreans. For him, the war was waged between China and the US. “The Americans were invaders,” he says.

North Koreans also believed they were defending against an invasion. On the afternoon of the invasion, Kim Il Sung, the Soviet-backed founder of the North Korean state, said in a radio broadcast that the country’s troops crossed the 38th parallel to retaliate against a raid ordered by “bandit traitor Syngman Rhee,” (pdf, p. 21) South Korea’s leader.

Luo, part of the People’s Liberation Army’s first motorized division, was sent to North Korea to supply the frontlines in 1952. When he first crossed into North Korea, he was struck by the destruction everywhere. He saw some of the bombing raids first hand—including one on the city of Kusong, from about 10 kilometers (6 miles) away.

“We saw four planes fly circles around the city, in a formation like the Cartesian coordinates we learned in primary school,” he says. “One circle, dong-dong-dong-dong. Another circle, dong-dong-dong-dong. And the city was gone.”

To avoid the US bombers, his unit operated at night. They were trained to empty a train in less than five minutes on its arrival—it took 10 to 15 trucks, each with 10 soldiers, to load all the goods from one carriage. Luo’s record was 10 round trips in a single night, with him and his comrades taking turns to drive their Soviet trucks.

The troops snatched lighter moments when they could—Luo’s battalion once joined a large group of North Korean civilians to watch a Peking opera performance at a military camp deep inside a forest north of Pyongyang. As the audience of 1,000 listened to the singers, a US bomber passed right above their heads, but didn’t spot them. “If it had dropped a bomb, everything is over,” he says with a laugh.

The truce

Sal Scarlato, too, remembers mostly fighting Chinese soldiers. “From 1952 on was strictly Chinese,” he says. It was in one such battle with Chinese fighters that he suffered a serious injury. “From the corner of my right eye, I see somebody throw something—it was a grenade… there was three of us, one got killed, another wounded, I rolled downhill.”

South Korean stretcher bearers ran to collect him and a nurse gave him a shot of morphine. After four weeks on a hospital ship, he went back to fighting, and eventually returned home on leave in March 1953. Scarlato wouldn’t go back to Korea for four decades; while home, his injuries flared back up and he was sent to a naval hospital in North Carolina in June 1953.

A month later, the armistice was signed in the village of Panmunjom.

Scarlato was recuperating in a hospital ward when a nurse rushed in yelling, and began pouring out drinks for all the patients—many of them, like him, wounded in the fighting in Korea. Scarlato, unfortunately, had been given his medicine just before the toast. He marked the armistice with a vigorous bout of vomiting.

In all, some 37,000 American troops had been killed, and nearly 100,000 wounded. Nearly 200,000 Chinese soldiers died. But the vast majority of the millions killed or injured in the war were Koreans. In the South, 1.2 million died, 80% of them civilians. In the North, a million were killed, more than half civilians.

Forgetting, recovering, remembering

Three years after the war ended, Kim Jong-hwan got married. He became a civil servant, working at the country’s new communications ministry for the next 36 years. Kim Seong-yeol opened a women’s goods shop, and did well—he was able to pursue his dream to go to college and got a degree about a decade after the war, when he was nearly 30. After the war, making South Korea prosper was a way to continue their patriotic contributions.

“I worked night and day to help Korea develop,” he says. “My daughters’ businesses are all doing very well. This is very good for our nation.”

Each the father of four, both men say they have done their best to inculcate the same sense of duty in the next generation. “Since my kids were little, I talked to them about this almost every day, so my children feel the same as I do,” said Kim Jong-hwan.

Because of the enormous American and Chinese presence, the Korean War is often seen mainly as a Cold War conflict. But its roots were in the 30 years of Japanese occupation that preceded it, and the bitter divisions that created among Koreans.

South Korea’s first president Syngman Rhee was an American-educated capitalist, but also known for his harsh repression of South Korea’s communist sympathizers. In the decades after the war, the country went through periods of authoritarian rule. By the end of the 1980s, however, South Korea had turned decisively towards democracy. Last year, unrelenting protests by South Koreans led to the impeachment of hawkish president Park Geun-hye over corruption, paving the way for the more conciliatory Moon Jae-in’s election.

“We created a nation. That’s what we created,” says Scarlato. “We fought, we won, and we made a democratic country… we were like a farmer planting a seed, and the Korean people made it grow.”

Luo, in China, remembers it differently. It was China that won the war, Luo says, because they knew themselves to be fighting for a righteous cause. “The victory is dependent on our thinking,” he says. He recalls the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army’s official song, with lyrics that roughly translate as, “Valiantly, spiritedly, crossing the Yalu River, fighting for peace, defending the motherland, and our hometowns.” (The Yalu river separates China and North Korea.)

Back in the US, Scarlato locked Korea away in a black box. He wasn’t the only one—the Korean War didn’t receive the same attention that World War II or, later, the Vietnam War, did. It was dubbed the Forgotten War—an odd title for a $30 billion (pdf, p. 5) conflict in which nearly 1.8 million American soldiers fought, and which set the US on a permanent war footing in Asia for generations. “When the war ended, that life was blacked out,” said Scarlato, who had dropped out of school early and, after the war, retrained for a career designing electrical systems for aircraft.

He reconnected with the war when Korean veterans’ groups started popping up in the late ’80s. He started to notice something curious—every couple of months, a fresh bouquet of flowers would appear at a Korean War monument in a neighboring Long Island town. Passing by one day, he spotted a man laying roses at its foot. Scarlato bolted over, and found himself meeting his first South Korean since the war. He went back to South Korea for the first time in 1994, has been back seven times since, and recently met president Moon in New York.

South Korea never forgot the war—or the soldiers who fought. On June 6, Memorial Day, it honors fallen Korean soldiers with a ceremony at the National Cemetery in Seoul. On July 27, the day of the signing of the armistice, it celebrates its veterans, and pays for foreign ones to come back and visit. In 2014, Kim Seong-yeol traveled to New York City to meet with American Korean War veterans—and still keeps the pictures of the gathering on his phone.

One the other side of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) now dividing the two countries, on July 27, North Koreans celebrate the Day of Victory in the Great Fatherland Liberation War. The war decimated their country—the US dropped 635,000 tons of explosives on the North, more than in the entire Pacific theater of World War II. But from the Kim regime’s point of view, it was a triumph nevertheless. It had fought the world’s most important power to a standstill.

Hope, surprise, wariness

The day of the April 27 summit between Moon and Kim, a local veteran affairs’ office in Seoul held a viewing party. “We all watched the summit together here on TV at the veterans’ affairs office,” says Kim Jong-hwan. “The mood was very cheerful—but people were also asking, ‘Is this really happening?’ One person said, ‘it has to be different this time!’”

There have been past summits between the two Koreas, and many failed efforts at peace and denuclearization—yet some things are different this time. That day, Kim Jong Un became the first North Korean leader to cross the border since the war. The two men shook hands, and unexpectedly, Moon briefly stepped back across the border with Kim. Later in the day, they hugged.

Thousands of miles and 13 hours away, Scarlato was watching in amazement in the den of his Long Island, New York home. “I was very surprised,” he says. “Shaking hands is one thing but hugging him and patting him on the back… [Kim] patting him on the back could be stabbing him in the back.” From his hospital room, Luo too caught the live broadcast of the border crossing on state-run television—but his reaction to the camaraderie is best summed up as a shrug.

There are plenty of reasons to be wary—including the lack of clarity about Kim Jong Un’s objective, and the complexity of the details to be worked out to get a peace deal.

The four-page armistice agreement, intended to be temporary, took 158 meetings spread over two years and 17 days to achieve. It recommended that representatives of the governments on both sides of the war meet in three months to begin peace negotiations. This year marks the 65th anniversary of that agreement.

“I thought the armistice would only last for three years,” says Kim Jong-hwan. “It’s gone on for too long, we need to have peace as soon as possible on the peninsula for the next generation.”

—Sookyoung Lee contributed to this article.