Donald Trump loves to hate on the US-China trade deficit. Ironically, these days that deficit proving to be a source of tactical strength.

As the White House trade war with China intensifies, the huge amount of goods that Americans import from China has become the means by which Trump can keep upping the ante, threatening ever-increasing amounts of tariffs. China, by contrast, is running out of US goods to slap duties on. The Trump administration is now threatening $200 billion in additional tariffs on Chinese goods. China can’t match that, since it imports way less. (In 2017, it only imported around $150 billion of American goods.)

But the Chinese government doesn’t need tariffs to punish American companies. After all, it wields the power of the world’s biggest propaganda machine.

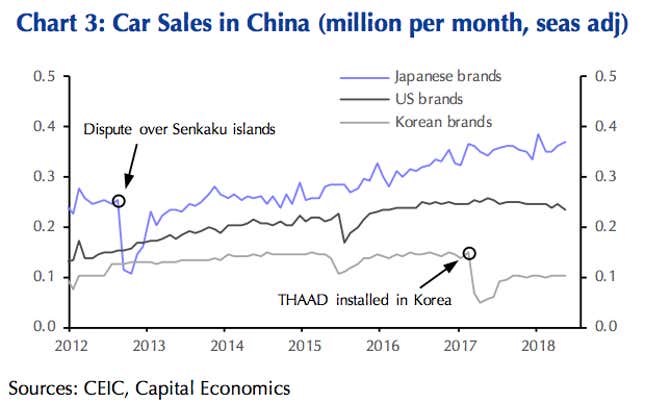

As the eye-opening chart below shows, the recent past offers a couple prime examples how swift and effective the Chinese government’s attacks on foreign companies can be, as Mark Williams, economist at Capital Economics, explained in a note Tuesday (June 19).

In 2012, for instance, when the spat between Japan and China over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands heated up, the Chinese government’s anti-Japanese propaganda caused sales of Japanese cars to plunge around 50% in a single month. The same thing happened to Korean companies last year, thanks to a dispute with China over the installation of a US anti-missile system in South Korea (its acronym, mentioned in the chart below, is THAAD). During that dispute, a Chinese consumer boycott also dealt a brutal blow to Korean makeup companies, as well as to its tourism sector and K-pop juggernaut.

One benefit to the tactic of using propaganda to punish other countries is that it gives the Chinese government plausible deniability. Officials can “remain at arm’s length from the resulting disruption to sales,” says Williams.

Most of the Japanese and Korean products that took a hit during those disputes were actually produced in China, which meant that the punishment could have been somewhat self-defeating. But switching to buying Chinese—instead of American—brands would be unlikely to hurt China’s economy in aggregate. Plus, says Williams, “in the event of a further escalation of the trade dispute, China’s officials would likely be willing to put up with some pain rather than give in.”